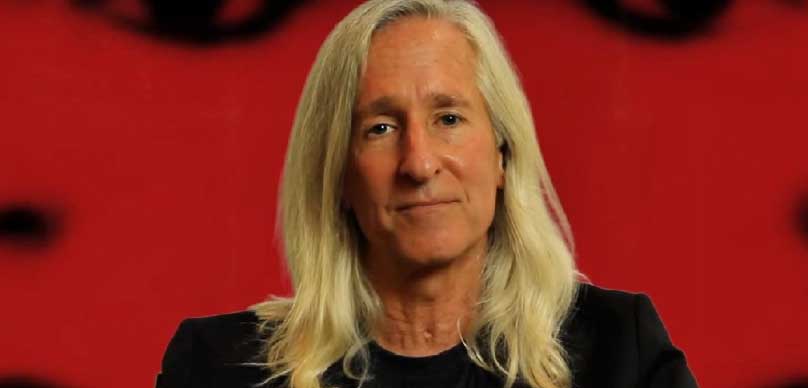

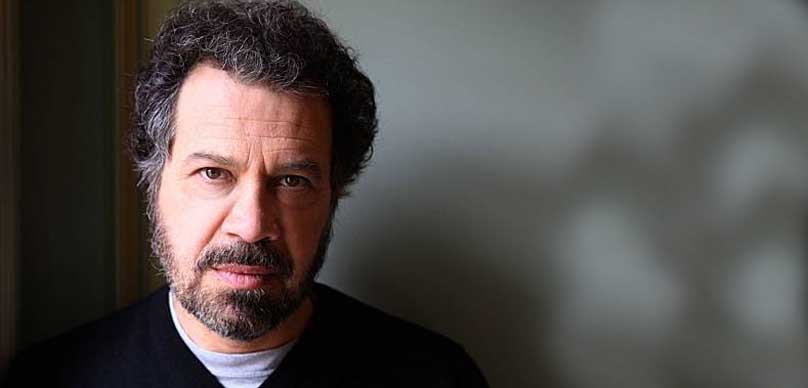

I am extremely excited to have on the show today a fellow podcaster, established producer, director, and writer, Mick Garris. Mick’s podcast, Post Mortem with Mick Garris, dives deep into the devious minds of the greatest filmmakers and creators of your worst nightmares to bring their distinctive visions to life in fascinating one-on-one conversations.

He’s renowned for his classic screen adaptation of Stephen King’s books like Sleepwalkers (1992), The Shinning and The Stand. and creator of 2005, Masters of Horror series.

The California native began his passion for storytelling as early as 12 years old – writing short stories. He launched his passion onto the journalism path at just 16 years old. Driven by curiosity, he freelanced as a film and music critic and landed interviews with the likes of Jimi Hendrix, Rod Serling, and Ray Bradbury in the 70s.

It’s remarkable what Mick accomplished in a time where everyone needed to know someone to get a foot in the door, let alone that early in life and without the help of social media. I guess folks were intrigued by his talent and drive.

While doing film criticism, Mick wrote specs, publications for magazines, and did some filming on 8mm. The guy lived the dream. The hard work began to pay off. His agent, Rick Jaffa read some of his specs, believed in him, and introduced Mick to Steven Spielberg. Mick ended up writing the first episode of the Spielberg sci-fi series, Amazing Stories, and seven other episodes.

He’s credited for writing screenplays like Psycho IV: The Beginning, Fly II, and the She-Wolf of London series. He was also was an editor on Spielberg’s other project, *Batteries Not Included, in which aliens help a feisty old New York couple in their battle against the ruthless land developer who’s out to evict them.

Garris has written and directed a lot of other horror classics such as Halloween comedy favorite, Hocus Pocus. The film follows a villainous comedic trio of witches who are inadvertently resurrected by a teenage boy in Salem, Massachusetts, on Halloween night.

Garris and I talked about his incredibly difficult yet fun experience shooting his small budget directorial debut, feature sequel Critters 2. In the film, Eggs of the small but voracious alien creatures called Crites are left behind on earth and, after hatching, set their appetites on the small farm town of Grover’s Bend.

The man’s contribution to the horror genre has amazing. Can’t wait for you to catch up on my conversation with Mick Garris.

Right-click here to download the MP3

LINKS

- Mick Garris – IMDB

- Post Mortem with Mick Garris – Podcast

- Watch: Critters 2 – Amazon

- Mick Garris interviews

SPONSORS

- Bulletproof Script Coverage – Get Your Screenplay Read by Hollywood Professionals

- Audible – Get a Free Screenwriting Audiobook

Alex Ferrari 0:15

I'd like to welcome to the show, Mick garris. How you doing, Mick?

Mick Garris 0:18

Great, Alex, thank you for having me.

Alex Ferrari 0:21

Thank you so much for coming on the show. Like I was telling you earlier, I was extremely excited that you agreed to do the show because you're you're your own established podcaster as well with with a great show. And you you've interviewed some giants in the business as well. So I was I was humbled that you said Yes, sir. So thank you so much.

Mick Garris 0:42

Well, I'm humbled that I'm able to work with some of my heroes. And it's a pretty exciting thing.

Alex Ferrari 0:48

Yeah, absolutely. So, um, let me ask you, how did you get started in the business?

Mick Garris 0:55

It's sort of a long story. But I had been writing since I was 12 years old, I wrote short stories and all that sort of thing. And, you know, I was born in LA so but no one in my family had any kind of connections to the entertainment business or anything. And so I started out as a journalist, and I interviewed people when I was like 16 years old, like Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin and stuff in music. That's about right, Bradbury was my first interview, and Rod Serling was my second. So so I was always able to meet my heroes and learn about them, you know, something that was always really important to me was my curiosity. So I was doing film criticism and interviews and writing screenplays on spec and trying to make a go of it. And I finally had some material that made for agents wanting to meet me and maybe work with me, because an agent only wants to represent you if they think they think that it's easy to sell you. If you are a marketable commodity, it doesn't matter how nice a person you are, or you know how well you play with others. But if they feel that they can make money off of you, it's great. So I went through a couple of agents who never really did me any good. And I was, you know, making my living working at Tower Records and that sort of thing. My first job was as a receptionist at George Lucas's Star Wars Corporation, during the first Star Wars. And I actually operated our two D two on the Oscars that year, but I was basically a receptionist. But it allowed me entree to the universal lot and looking at how people made movies seeing Alfred Hitchcock on the lot towards the end of his life. And finally, a an agent named Rick Jaffa, who is now a very successful screenwriter with his wife and partner, Amanda silver. He was an agent at William Morris. And he was the first guy who read my stuff believed in me and actually got my material in front of Steven Spielberg's company. So I was doing publicity. And I'd hire myself to do making of is because it was a lot more affordable than the studio would spend. And it would give me film school on how to take pieces of film and put them together into a narrative, even in a documentary or documentary format. So I did the making of Gremlins, I did the making of The Goonies. And the first, I had an interview show on the Z channel, which was the first pay TV channel in Los Angeles. So I would interview filmmakers, who made the films that were scheduled to come up on the Z channel schedule. And one of those filmmakers was Steven Spielberg. And after we did the show, I mean, I'm doing all the talking here, Alex, but

Alex Ferrari 4:07

don't quote me, please.

Mick Garris 4:09

But after the show, he said, You know, I really enjoyed that. And he doesn't. He didn't usually enjoy all the interviews that people normally ask all the same canned questions and all but there was a shared passion for movies from a similar background as my own. So when I was making the making of The Goonies, on the first day of shooting in Astoria, Oregon, I was setting up the camera man was setting up the lighting and stuff to interview Steven for the documentary. And he said, You must do a lot of these sorts of things. And I said, what nobody should ever say to Steven Spielberg was I'm trying to do less because I'm trying to make a go of it as a screenwriter.

Alex Ferrari 4:56

What I really want to do is direct Steven, right? Yeah.

Mick Garris 4:59

Well I would never say something like that today, however, then he said, Oh, really we're looking for writers for this new show I'm doing called amazing stories. So it turned out, my agent had gotten amblin, a spec script of mine called uncle Willie, that is still never been made. But I got to read the coverage that they did in the last three words of the coverage were higher this man. So Stephen called me and asked me to, to write the first episode of amazing stories that was ever written. And I wrote it in three days. I mean, it was like a call from Steven Spielberg. And I'd

Alex Ferrari 5:42

love to do it. And by the way, for everyone listening, it's Steven Spielberg at circa what 8485.

Mick Garris 5:48

This was in 1985 85. So

Alex Ferrari 5:51

it's post, et and everything else he did prior to that. So he's already Steven Spielberg. He's been Steven Spielberg for quite some time. So it's like, basically, a god coming down from Mount Olympus and touching you on the shoulder and go, you now shall right.

Mick Garris 6:06

So yeah, I mean, we get a phone call. And I pick it up and Steven Spielberg calling from Mackerras and I'm looking at my wife and our little crackerbox house in the valley. And then they asked me to adapt, write a screenplay based on one of his two paragraph story ideas for amazing stories. And I knocked it out in three days. And they read it and asked me to do another one. And then a day and a half into it. I'm only halfway through. And he and Kathy Kennedy called me to ask me if I would go on staff as the story editor. And I had never done anything like this before. And so suddenly, I'm in $100,000, a year job back in 1985. Oh, and I was, I was on food stamps, when I got the job, also. So it's a convoluted story, but that's how I got my first writing job.

Alex Ferrari 7:04

So and again, not a bad first job. And no as, as first jobs go, not too shabby, not too shabby. So, which, by the way, which were you I mean, I loved. I was obsessed with amazing stories when it came out. I watched. I mean, my favorite one. I still remember to this day. I mean, obviously the Kevin Costner one was fantastic, which we think was the first episode, wasn't it? Steven directed that one.

Mick Garris 7:29

It was the second season the first episode,

Alex Ferrari 7:33

that one and I remember the train. I think Stevens did the train. Both of those. Yeah, right. I remember those two. But my favorite amazing story besides when Santa's got arrested, which was fantastic. Was the episode where the kid had the goo that you poured it on a picture and the picture came to life and right he was like a horny college kid. And he just was trying to get this girl on and you would get half a girl or too big of a girl and right. It was like trying to get it perfectly. Whoever kissed the girl first it was it was theirs forever. It was it was just obviously because was such a dream for any adolescents. And adults, obviously. And I love the ending of that. I'll never forget it. Sorry, spoiler alert for everybody. But it just spills onto Fangoria magazine or something like that. And it just fades to black. It was like, Oh, that's amazing. But I remember that show. So well. I guess I mean, that experience. I mean, it must have listened starting at that level must have. I didn't say Jay, did you what you understood later on that it's not all like that, like that was kind of like the red carpet.

Mick Garris 8:42

Right. But I was also 33 years old when it happened. So I had been writing for years and years and years. Like I said, since I was 12 years old is when I first seriously started writing. And so I've never gotten jaded about it, you know, the excitement of being able to do what you dream of doing. A lot of people get spoiled by it, and expect their lives to continue to be at the top of the heap. I'm always concerned that I'm gonna fuck it up. And you know it every time especially directing every time I I do it, I feel like it's my first time out and that I've got a lot to prove and, and being contemporary and being aware of the technology of filmmaking as it as it metamorphosis sizes. But as far as writing goes, writing has always been I'm a rather fast style writer, in that it comes easily to me and I love it. And I'm just lucky to have been born with a facility for writing and, and I I'm good with language and stories come to me quickly. I mean When I'm writing on spec, which is almost all the writing I do, I just sit down on page one, I don't do an outline or anything, I have an idea. And then I just plow into it and let the tributaries take me where as they will.

Alex Ferrari 10:14

But when you say that, and I've heard other various other screenwriters say the same thing, but do you agree that, you know first for screenwriters just starting out? You're able to do that, because you've been writing forever. So the structure and the you already almost instinctively know how to structure the story in a screenplay from stage one when you don't have the outline? But from somebody who's just starting out, would structuring them outline makes sense?

Mick Garris 10:41

Well, I think it depends on the writer, every writer works differently. And for me, I started out that way. Because I'd been writing but not writing screenwriting, I've been writing short stories in the leg for a while. But I've always watched movies and television my whole life. And I think that there's an intuition that grows within you, as you consume. Screen storytelling. So when you're writing on assignment, you have to do those steps, you do a treatment, and then you do an outline, and then you do a draft. And then because every step of the way, you're going to get interference from the studio executives, from the director, if you're not the director, and all of those sorts of things. So every way is valid for me. I used to think Wouldn't it be great if I took six months to write a script, think how good it would be. And for me, if I took six months to write a script, that means I'm having trouble and it's, it's labor, it's not, it's not coming out, like the magic, it's not storytelling, it's a job. And so I am lucky to be able to write quickly and and Lee and fairly simply, but, again, on the jobs where it's an assignment, then you have to take each step at a time. And then it's never your own unfiltered storytelling, you know, you're going through the hands of a lot of other people.

Alex Ferrari 12:12

Now, do you start with plot or with character, like when you sit down? Are you Do you already have a plot in your head? Or are you starting with the characters like, let's see where this guy or this gals adventure goes?

Mick Garris 12:23

Well, it's kind of half and half, I'll usually start with a character. And of course, every character you write, I tend to write my fiction, even I write books as well. A lot of my fiction is written in the first in the first person, and when you're writing a screenplay, every character is the first person. So they're always some facet of who the writer is, or who he or she imagines he is, or would like to be. It's, it's just a matter of empathy. And usually, I'll have an idea of a character who is some what thwarted in his life, whether it's romantically or ambitions. You know, there's there's a roadblock, and that roadblock is part of what the story is. And then I'll take a combination of who that character is and why his his quest is not an easy one.

Alex Ferrari 13:21

Now, when you said earlier that you you know, you shot a lot of making of documentaries of films, like the thing in Goonies and yeah, is it Gremlins as well? Yeah, so you're on the set with, you know, a Rogue's gallery of some of the most amazing directors of their generations. What were some of the biggest lessons you learned from just just being there and watching their process day in because as I'm making up, you're there every day shooting? What's going on?

Mick Garris 13:54

If you're lucky with the budgets we had, I was there for a couple of days or a few days out of the production schedule. But surprisingly, the thing I learned most is how much of the movie is directed off the set the conversations with the production designer with a dp with the actors, all of those things, you're really seeing almost the finished product when you are on the set and watching them work. That said, watching how a director elicits a performance from an actor. You know, the lighting is already been planned out. The shots in general have been planned out depending on what the director style is. But the job of a director is to communicate. And a writer doesn't have to be very communicative. They're very different disciplines. A writer is monastic and own and mystic in a way, where as a director is confronted with being a social animal, he has to be able to To communicate, not only communicate what the overall movie is, so that each department head and each actor isn't making a different movie choice, but to be able to instill enthusiasm and confidence and excitement that they're doing something special, and to be encouraging people, whether they're cast or crew to do their best work, because they're going to make something really special together. And, you know, there are directors who are directors because they enjoy being autocratic. They like to be the boss, and they like to throw their weight around. Nobody's going to do their best work for somebody who yells at them. You get their best work by being a teammate and somebody who encourages the best ideas from every department, even if it's craft services. Somebody from craft Services has a good idea. I'll take it, you know?

Alex Ferrari 15:54

Yeah, absolutely. Not you, you. Your first Is this your first feature or one of your first features that you wrote? was called Batteries not included? Which Yeah, I have an absurd absurd love for because I remember it. I remembered it and everyone listening, please forgive me back in my video store days. When I was there, renting it out and recommending it to people. And it was a Steven Spielberg produced film. I remember you also co wrote that with a another. He's done okay for himself, Brad Bird, as well. Yeah. So how was it like coming up with that it was very cute, just adorable. It's just like an adorable.

Mick Garris 16:34

Well, it's, it's what Spielberg was known for in the day. So that story was originally an amazing stories episode called Gramps and Grammy and company. The idea was Stevens, he wrote out a paragraph or two. And then I wrote a screenplay for the TV show. And then he changed his mind and said, I think this idea is big enough for a feature film. So I wrote the feature film script, I wrote two or three drafts. And And then, when Steven brought in Matthew Robins to direct Matthew Robins brought in Brad Bird with whom he had written before. In fact, the first script I wrote for amazing stories was the magnet kid. And Matthew Robins directed that and he brought in Brad Bird. So I didn't write with Matthew or Brad. As you know, when it's a writing team, there's an ampersand between your names. And if you're writing and rewriting somebody, there's an and between your names. And I've been lucky enough to be the first writer on virtually every movie that I'm a screenwriter and not a director on. So yeah, it was very much Stephens idea. And Matthew Robins had co written Stephens first movie, the Sugar Land Express. And so he felt very, very beholden to him and gave Matthew an opportunity to do a big Hollywood studio picture, which worked out really well for him. But yeah, it started and ended with Steven Spielberg,

Alex Ferrari 18:15

as it as it always does. I mean, I've had the pleasure of speaking to some amazing filmmakers and writers on this show. And I cannot and I say this all the time, I cannot believe the the the Spielberg touch, he has touched so many careers, of filmmakers. I had john Lee Hancock on I had Kevin Reynolds on and they were telling me something like I had no idea that that that Spielberg was the one that kind of crack the door open for them. And he's, he's done that for so so many people around this, this business. It's, it's remarkable a truly truly is.

Mick Garris 18:57

It's kind of what he wanted to do with amazing stories. Yes. Get Martin Scorsese, and Clint Eastwood and you know, mucky muck directors. But he also gave first time opportunities to people like me, and Todd Holland, and Leslie linka glatter. And Kevin Reynolds, you know, directed one of the episodes. So, he really wanted it to be kind of a flower box for for new blooming directors and, and it was an opportunity you don't often get,

Alex Ferrari 19:30

yeah, and he's just, it just never ceases to amaze me the influence that that Stephen has had on on Hollywood history, not only for himself, but the opportunities he's given to so many people along the way. It's been pretty remarkable. I have to say that you're I think it was your first directorial film, critters too. Now, the time was classic, the time is close. So obviously, there were questions left over from critters, one that needed to be addressed. In a sequel, obviously,

Mick Garris 20:01

it was an absolutely necessary sequel that the world could not have lived without, until it came out. And opening night I went to my local theater in Universal City, and there were three people in the audience.

Alex Ferrari 20:15

So, how did you I mean, listen, I remember I remember critters do I remember critters? It was obviously after after Gremlins, so it was kind of like write a spin off of Gremlins. And there was to be charitable, it was a spin off, it's actually to be but to be fair, to be fair, there was one that was even a little bit more ghoulies was even actually a little little less, less connected to the original

Mick Garris 20:42

material. That's for sure. There's spooky there's ghoulies there's all kinds of little creature movies out there

Alex Ferrari 20:49

after Gremlins. Yeah, but so it was what it was your first shot directing really wasn't it?

Mick Garris 20:54

Well, I directed an episode of amazing stories, right. And before that, I directed, wrote and directed a Disney TV movie, which was my very first a one hour movie called fuzz bucket. That was a story that Steven rejected for amazing store.

Alex Ferrari 21:11

Fair enough. So well, kritis was, but that was, but it was a sequel. It was, you know, it was had a decent budget, if I remember,

Mick Garris 21:19

well, you know, for what we were doing. Your original critters was much better than anybody expected it to be. It was a $2 million movie, which, for a little indie, little creature movie was not insubstantial. And it was mildly successful at the box office, but made most of its money on home video. And so they decided, Well, time for critters to. And I think the reason I was hired, and Bob Shea, who was the head of new wine, gave me the opportunity to do this for four, which I will always be indebted. But David to he had written a script. And he was very happy where it was Bob Shea felt that it needed more. And rather than just hire another writer, the idea was to hire a writer, or director. So it would be a much easier game to to actually have the shooting script done by the director. And I believe that because kritters was very spielbergian in it's in the first movie and even more so in the second that they wanted an associate of Steven Spielberg, so maybe some of his pixie dust would rub off on the project. And because stylistically, you know, I absolutely was influenced by Steven Spielberg and Joe Dante in the making of critters to and by Warner Brothers cartoons and all those things. But the idea of Norman Rockwell goes to hell is something that fits very, very well into the Spielberg canon. And I think that's what they were looking for at New Line. You know, it was a PG 13. It wasn't an R rated horror movie. And, you know, we got away with one naked lady and some some critter violence that wasn't too incendiary. But yeah, it was an opportunity to be both writer and director. And it was on a scale that I thought was so manageable. However, it was special effects, kids, animals. You know, they had a

Alex Ferrari 23:30

trifecta.

Mick Garris 23:31

Yeah, action scenes, all this on a $4 million budget. And with that $4 million, we built the town, we did all kinds of amazing things. So we got a lot of bang for the buck. But, you know, Gremlins was made for $10 million. And Gremlins two was made for $60 million. So

Alex Ferrari 23:52

$60 million of Gremlins two cost. I think so I think that's a lot for that time period. That's it.

Mick Garris 24:00

It definitely is. But it came well after the first one. So

Alex Ferrari 24:04

yeah. Wow, that's remarkable. Now after krytus, two, you jumped on to another sequel, writing from from another successful another successful first film the fly, which is arguably a you know, classic at this point. And I would say so yeah. I love that film with a passion. Oh, God. And I mean, Jeff Goldblum in that kind of made Jeff Goldblum like that. And, I mean, Jeff had been acting for a while but that's I mean, I remember when that came out. Everybody was talking about the fly was like in his Cronenberg in you know, in his element of is fantastic. Now you pick then, of course, you get dawn, the daunting task of writing the sequel to a very successful loved film. How did you write Roche writing a sequel to such a hit

Mick Garris 24:50

very differently than what you see in the movie that that has, that was made. You know, I was the first writer on that and I came up with an idea I wanted it to be as respectable as the Cronenberg film. I Cronenberg is a friend, I love his work to death, and the depth and intelligence and humanity of that movie was something you rarely get any genre film, especially a monster movie, which, when you come down to it, it's that's what it is. But it's so much more than that. It's a romance. It's an impossible romance, which is a theme I really like and return to time and again, in my own work, fiction and film work. But so my idea was something quite different. It had to do with giving the baby up for adoption, because you know, she was going to have an abortion. But the original idea was that it would be an evangelistic group that takes the baby from her, as they do with other young mothers who don't want to abort, give it a good Christian household, but they are training it and all these other children in the way that in the Soviet Union in Russia and the 30s, they did lots of experiments where they would exercise children, mentally and physically to be far beyond the powers of mortal men and women. They would develop their psychic abilities, they would give them Olympic Training from from toddlerhood on, so that they would become superheroes, basically in reality. And, you know, I wanted it to be a Christian army sort of thing. So it was a really interesting, adult kind of attitude. But the head of the studio, wanted a teenage monster movie. First, Scott Rudin was our our production executive. And he's great and has gone on to produce a bunch of really high end movies for the Coen Brothers for lots of other people, has run into some metoo issues in the last year or two. But there was a change in management and wondered Goldberg, who was half of spelling Goldberg, the people who made The Love Boat and other TV shows, letter, Goldberg was named the head of the film studio, which was very controversial at the time, because he'd only done television and not features. And when a Goldberg wanted a teenage monster movie, so there was a lot of infighting between Scott Rudin and Leonard Goldberg. And I was, you know, in the middle, and trying to accommodate both masters and the opportunity, the author of critters two came to me. And so I had to leave had to leave the project to fly to which was in the middle of all those problems. Then Frank Darabont inherited all of those problems. Frank Darabont was the second writer and then Jim and Ken wheat, who had done it young Indiana Jones and some other things. They were the final writers on it. So it changed quite a bit from where I was and where it ended up.

Alex Ferrari 28:11

And Frank and also Frank did okay, as well, I think he's done. All right. He's done it. He's done. He's done. I think he's done a couple other things. I'm not sure what but he's done wonderful. things as well. Now, another film that you directed, which you didn't write, but you directed, and arguably was one of my favorite films. Growing up in the horror genre was sleepwalkers, I absolutely adored sleep walkers. And not just because it was it was just a cool, I must have been I was in high school, probably when that came out. So I'm dating myself, but I was probably around high school time when that came out. And I had the largest crush in the world on match anomic I mean, you're not alone. It wasn't just me, I'm sure. But I mean, holy cow. She was amazing. I just adored her, and then forgot the lead actress named who's also in the palace, Krieger. Yes, it was also a Blue Lagoon and charmed and Brian Crowe. Brian. Yes. broadcast. Thank you. Let's return to the Blue Lagoon. Yes, return to the blue the good. And then he went on to charmed and all that now it's kriega from ghost story. Yes, exactly. It's, it was remarkable. But you wrote an A you directed an original screenplay by Mr. Stephen King. Not too shabby. A writer himself. And he doesn't. I don't think he does. He I think this is one of the this was an original screenplay that had nothing to do with original material. So it was an

Mick Garris 29:42

original, his first original screenplay to be produced. Correct. And what was the slide? Oh, yeah. Well, I never met him until I screened it for him afterwards, but we would talk on the phone. And he was incredible. I mean, we've since become very good friends that have worked together a lot. And I'm lucky enough to have had four projects that he wrote the screenplays for himself. sleepwalkers was the first one. It was also my first studio movie as a director, and really my only studio movie as a director, feature film, all of the other stuff I've done has either been television or independent. And then after that, I mean, we got along so great. And he was so happy with how sleepwalkers turned out. And the battles that we had to fight together, that he asked me to do the stand the next year. And I had only done movies of a relatively small scale. And then along comes the stand, which is 100 shooting days, six states 126 speaking roles. I mean, always on the road. Just Yeah, massive and and that experience was also my first experience with an unmitigated success. sleepwalkers opened as number one in the movie theaters in America that year, that week, but dropped out very quickly. The stand became the highest rated miniseries ever. The four nights it ran, it was number 123 and four that week, but each of the nights went up. It was 50 million people watched it in North America each night. But it went up each of those four nights, which is very rare. And, you know, it was it was incredible to have made something first of all with Stephen King. But secondly, that cast I mean, Gary Sinise and Ruby Dee and Ossie Davis and Matt frewer. And Rob Lowe, and, you know, so many people, but also to go into a supermarket and hear people talking about it the next day. You know, see, it's not something that happens very often. And you know, nothing I've done ever reached the heights of what the stand did. Well, except Hocus Pocus.

Alex Ferrari 32:08

Yeah, well, we'll get we'll get to Hocus Pocus on Reddit,

Mick Garris 32:11

which was actually written eight years before it was made. Right. My draft Anyway, there are 11 other people on it after me. But we'll get to that. But to to have your work talked about when nobody knows that I was the guy who directed it. And I'm standing in a supermarket line listening to people talking about how much they enjoyed it is an experience that is so odd and wonderful and thrilling.

Alex Ferrari 32:40

Yeah, I mean it. When I have guests on the show who have had obscene success, and a project, I always ask them what it's like to be in the, in the center of the hurricane when it comes into that kind of stuff. And for you it was the stand. And you know, 50 million plus people watching your work in the night in the 90s on television. Yeah, is something it is a major deal within the Zeitgeist. It was in the Zeitgeist wasn't it?

Mick Garris 33:10

It was and still is, you know, people still talk about it with the remake having just been done last year. It's amazing. And yet, because it happened on television, probably more people saw it than anybody saw any movie in the theater, but it's television. It's immediate, and then it's gone. It comes back on home video, but it's gone. So Spielberg wanted King and myself to do a movie with him together that King wrote called Rose Red, which became a mini series later when King and Spielberg couldn't agree on the direction it went. There was an 800 pound gorilla on each side. It was about

the size two juggernauts the 50 pound champion the wearing a banana suit, yes.

So, you know, because it didn't happen in a theatrical film. It's not the same as being in the eye of a hurricane. If your movie is in theaters and number one week after week after week, there it's a totally different thing. Plus, it's not the director, especially in television who is brought attention to and in this case, Stephen King not only produced it, but he wrote the screenplay himself. And so I've always been under the wing of either Steven Spielberg or Stephen King or any other Steve's you can think of but, but which is fine, but it doesn't bring attention to the person who is not the famous person on board. And, you know, I'm happy to be a guy behind the camera anyway. But, but career moves, you know, the this Rose Red project never happened. So I Didn't direct for another three years after having directed this massive success. So

Alex Ferrari 35:05

insane, that's insane. But to be fair, you know, being under the wing of either Stephen King or Steven Spielberg, not again, not a bad place to be in,

Mick Garris 35:13

I wouldn't change it for anything. luckiest guy I can imagine.

Alex Ferrari 35:18

It is it is pretty remarkable. And I know so many people are trying to break into it's like larceny, we're trying to break into the business. It's always like, I had a hacky, and I got a break, and I gotta get through the back door. Like it's, it's always something along those lines. Talking, and I'm sure you've come across this to talking to the people you've had on your show is things that happen a lot of times, it's just the right place, right time, kind of its right place. right time. There's, and all you could do is prepare you were waiting for 33 when when Steven showed up, and but you would have been preparing for that moment. All your life, essentially, yeah,

Mick Garris 35:55

it's not only right place and right time, but it's also the ability to deliver what people were looking for. And to be a person that people want to work with. Again, you know, if I were a producer, looking for a screenwriter, and I had some egomaniac pitching me in my office and telling me how to do things in the white, I no matter how good the story is, I don't know that I'd want to go through that process. But, you know, it's it's the ability to deliver to, you know, I was very lucky in that. At the time, I was confronted with Steven Spielberg, and I'm interviewing him on location for The Goonies, they were looking for something that I was capable of delivering, and that they saw, at the same time, my agent had sent to his people, a spec script to read. And so while I'm in Astoria, Oregon, while Steven Spielberg is in a story, Oregon, someone in Universal City is typing up coverage, saying they should hire this guy that he just spent time with. And, you know, the timing could not have been more fortuitous. And the good news was, there was material to back it up. That didn't come from me, but came from his development, people saying, take a look at this guy, we you should hire him. And I happened to be in front of him the day before he got.

Alex Ferrari 37:23

Now would you agree? You know, you've been in this business a long time. I've been in it over 25 plus years, you know, hacking away as well. I've dealt with people, the best advice I could give anybody trying to get into this business is don't be a dick. And I think that I think that is a mantra that a lot of filmmakers and screenwriters don't understand and you are a personification of it. Because it was because of you being so you know, you're able to work and connect with people like Steven, that he hired you again and hired you again. If you were if you were a dick, and that first that first pilot that you were writing the first episode you were writing at Kathy Kennedy and Stephen would have called you up like, do you want to be a story editor? And if that experience wouldn't have gone? Well, there's no batteries not included in your career could have gone on a completely different trajectory. Just by being obviously you have that talent and being able to provide the service that you said, you can write that nice is really something that a lot of screenwriters don't they underestimate how important because would you as a as a filmmaker and a producer, work with someone who might be slightly less talented or experienced, but wonderful to work with, as opposed to a much more superior writer, but just a complete ass? Well, no, I'd probably write it myself. But it's a general.

Mick Garris 38:47

Yeah, but no, that's probably true. I mean, I'd much rather write with somebody being if it's for me to direct. I'm going to write the last draft anyway. Sure. But yeah, you want to work with people who you respect their talents and their abilities, as well as being able to sit in a room and bounce ideas back and forth and have a good time doing it. You know, everything about making movies is incredibly difficult. And so the more fun you can have doing it, often it reflects now, it is often said that the hardest movies to make are the ones that come out the best. And that's not really true. And you can feel the camaraderie of of when a creative group is clicking with one another. But another thing about about screenwriting, is that spelling matters. It is literary, you know, it's, yes, it's a blueprint. And the the extreme example of that is Walter Hill shooting script for alien, which is just so spare and sparse and all but also, if you're writing a screenplay. You're not just laying down a blueprint. And first of all, you're not telling a director how to direct his shots. You know, that's not part of the job. But you are engaging the reader in the same way you would engage the reader of a novel, you want the descriptions, not only to just be guy goes in store sneezes, buys a box of Kleenex, you know, you, you want to embroider it with language that compels you. And it's not just strictly a schematic, which a lot of people feel it is. So being able to write well, writing fiction is a really good practice for writing screenplays, too, you know, Stephen King, you want to turn every page because he engages you, the humanity of his prose, the, you know, he writes very sparsely. But it is woven in such a way that it compels you to turn the page. And a screenplay needs to do that, too. It doesn't. It's not there just for an actor to mark in yellow marker, his dialogue, and not read the descriptions scenes in the scene in between. But those descriptions have to be compelling, they have to be interesting, and they can't just be nothing is harder for meter action movie script, where you're describing lots of action scenes in detail. I can't do it, I can't get through it. But, you know, anything that draws the reader in, whether it's fiction, or or screenwriting is the most important thing, you know, if, if, if writing had never been invented, if a camera came first, no one would have ever invented the written word. To take it down to, to cast it into history. But we have developed an ability to tell stories in engaging ways and the use of words. And grammar matters if I'm reading a script, and the first five pages have 42 typos and your and your are used improperly and things like that, I feel like I'm reading someone who is an amateur. And you want something that is more compelling than that.

Alex Ferrari 42:27

And also I have heard it referred to as the sea of white, you want that page to be a sea of white as much as you can be yet. But yet, especially in the descriptions, and I've said this many times on the show, I equate it to being a haiku, you got to really get a lot of information in with very sparse words. But you have to make it interesting for the reader, the shooting script could become something else. But the actual script that a reader reads a producer reads as a direct reads has to be that kind of thing that pops, but you can't, you can't spend

Mick Garris 43:00

it by, okay, go ahead and give you a description but make it captivating. You know, make it funny, make it really propulsive, you know, and I tend to fully capitalize important words in a script, whether it's introducing a new character or not, you know, I will make sure that you don't miss those important words they stick out.

Alex Ferrari 43:22

Right? It's it's, you don't have the luxury of writing a page on how that tissue feels. Right? where a lot of I've read a lot of scripts that do that, that the writer just like sits there and like, it's a 240 page script. Okay. You know, it's it's though,

Mick Garris 43:40

I'll tell you a story about Batteries not included. This, I felt my life was on the line. This was the biggest opportunity anybody had given me write a feature for universal and amblin and Steven Spielberg. My first draft was 140 pages. And beefy. Yeah, very. So I turned it in Ohio. It was a while before I heard back from Stephen. And then, you know, he called me into the office and I'm being dead honest here in painful ways. But he said, You know, it took me three sittings to read this script. And that's not a good thing. So but that was the best thing anybody could have said to me, and he did it. Because he wanted me to learn. He wasn't criticizing me. But he was telling me I'd fucked up. And so I took it to heart and I took it home. And I worked on it. I worked on brevity and I tightened it up and made it much better brought it in at 110 pages, and it got the green light. So I had learned my lesson, and it's a lesson that has stuck with me ever since.

Alex Ferrari 44:54

Now, you also worked with Stephen King, on the shining mini series, which is has a lot of being the shining. movie adaptations have a lot of lore behind it because of Stanley Kubrick's version and, and Steven, Mr. King finally came out and said, I despise it. I hate what he did with it. And I think that just two different things. I mean, Steve Stanley just did what he wanted with the material. Well, Kubrick did a Kubrick film and right not a king film,

Mick Garris 45:25

not a kenotic King film. And there's a big difference between them as artists. Kubrick is very cool. And King is very warm. The writing is all about the humanity. But also it's a very personal book to King. When he wrote it. He was a drinking alcoholic. And it was all about alcoholism and the guilt he felt for actually hurting his child breaking an arm of the character of jack Torrance, his child in a drunken rage. And so here he is recounting something that's personal to him. I I'm sure he never broke one of his son's arms. But, but he knew that there was a boiler that was gonna blow inside of jack Torrance, because he'd been in that boiler too. And so Kubrick turned it into something very chilly and very Other than that, and it became an iconic horror movie. But it was not a good adaptation of a Stephen King book. And that novel is one of my favorite novels of all time. And the good news was that Stephen King himself what after the success of the stand, ABC said to King, what do you want to do next? Anything you were all there? And he said, you know, I'd kind of like to do the shining like the book. And he wrote the script himself. And it's one of the best scripts I've ever read and certainly ever had my hands. And so because we had done so well with the stand together, and become friends on that, he trusted me with this three years later. And we were able to do something really special with that, too.

Alex Ferrari 47:03

Yeah, it was, it was remarkable. I love watching both versions and seeing the distinct differences between between your version and Stanley's version. And they live as different pieces of art in different ways. There's no glare on the same shelf in the video store. If we may go back to kids or kids just Google video store, you'll see it Yes. Very, very cool. Now, there was a there's a project or a film that you wrote that I don't think you thought and please correct me if I'm wrong, I didn't think you would think it would have the legs that has has had, nor the the love that has come from it. It was just Hocus Pocus. It's become this classic Hollywood Halloween film, but it's a Halloween family film. It which is pretty,

Mick Garris 47:57

which is pretty amazing to hit the you know, it was not particularly successful. Whatever came out, it was a very mild success, right. But over time, and it really started with the Disney Channel. They started running it on Halloween, and then ABC started doing it. And every year it gets bigger and bigger and bigger. And people keep asking about a sequel and all that that's finally about to start production, right. And the merchandise. It's the biggest Halloween movie in history.

Alex Ferrari 48:31

And bigger even bigger than Halloween.

Mick Garris 48:34

Yeah, I would have guessed. You know, on, on Halloween day on free form, they show it back to back 12 times on that day. And every day of the month of October they show it

Alex Ferrari 48:47

and my children finally just watched it. They're not there. They're young. They're young girls. And we watched it on Disney plus, because it came on Disney plus and we watched it and I hadn't seen it probably since the video store days. It's just I see clips in it, but I hadn't seen and I said they're like what is so much fun. It's just like a fun and like, Oh my god, they're making a sequel and they're all coming back. Oh my god.

Mick Garris 49:11

Yeah, great. Well, and it's it's again, I was hired to do that because I was working with Steven Spielberg at the time. And the producer, David Kirschner who came up with the idea designed all the characters and everything had just done an American tale for Spielberg and amblin. So it was to Spielberg guys getting together with, you know what Disney wanted. And at first, Steven was interested in being a part of it, that it was like, oh, with Disney. Now we're going after the same audience and they were very competitive at that time. So it was almost a collaboration with with Spielberg, Disney and sorry, my gardener is

Alex Ferrari 49:55

it's all good. It's all good. It's all good.

Mick Garris 49:57

It's not to me, but that's it. Thank you But, yeah, it's amazing to hit with something that you go out on Halloween night and you see children dressed as Billy butchers and the Sanderson sisters, and they carry their big book, you know, the book of spells. And it's like, I helped create that thing. You know, this thing exists partly because of me. And it. It's really humbling.

Alex Ferrari 50:28

Yeah, it's something that just lives on and on and on. And you've, you know, you've been a part of things that that have shelf life, I think Hocus Pocus arguably, is the is the thing that holds like it's just hold, it's been going on and on and on, and on and on.

Mick Garris 50:43

Absolutely, absolutely. in it. You know, I have had the fortune of having worked on things that were not successful initially, that became either cold favorites are much more successful in their afterlife than in their first lives, you know, critters to shows in theaters and festivals every Easter and on television and stuff. It's one of the few Easter horror movies and you don't see critters one revived, you see critters to revive. And psycho for was only on Showtime when it came out. And you know, it was written by the same guy who wrote psycho one. And, you know, it has developed a love and the stand. Huge, and it still maintains its its power and to be able to create something. Popular culture is very much of its moment. It's not meant to last forever. But fortunately, I've been involved in some projects that have had a very long shelf life and a shelf life that continues to grow. And so maybe it's better to have flops, that becomes

Alex Ferrari 52:00

I mean, the residual payments become better later, I guess.

Mick Garris 52:03

Yeah, I wish. You know how residuals work. They shrink every time.

Alex Ferrari 52:08

I know. But is it like Seinfeld? Where you get a penny? You get 1000 checks that are petty? Yes. Yeah. And the stamps are more. Yeah, that's something that a lot of a lot of writers think that. I think and I'd love to hear what you think about it, because I think things have changed so much over the last 10 years is you mean before I mean, I've known a lot of people in the gills and that get those residual checks. And they do get smaller every year. And but then it boosts up when a new new release comes out. Like oh, it just hit HBO. Okay, great, Greg, okay, just a video. But in nowadays, with streaming and everything, it's not what it was once before. So I think a lot of young writers coming into like, Oh, I gotta get that sweet, residual residual money. Like we're gonna live in the life like Seinfeld and friends. And I'm like, I don't think that even exists anymore. I think that's that, that kind of residual, like, I mean, for instance, those guys, oh,

Mick Garris 53:05

yeah. pay TV and theatrical and that sort of thing. And network television broadcast, cable television, those residuals live on. But in streaming, you know, Netflix doesn't pay residuals, even for their original programming. So you got to make a big deal upfront. But I don't know what I would do if I were a new filmmaker starting out, because there are movies made by filmmakers you would know and films you've seen, and that you know, that you like, that are familiar, where those filmmakers can't make a living off of what they get paid to make them for. You know, it's in the world of streaming, it's hard to separate the wheat from the chaff. You know, who knows, from a little thumbnail on amazon prime, if it's good, or if it's not, and, you know, Netflix will produce movies that they don't promote, and just say, let's see what happens, see if they hit. Or they'll make something like birdbox, which connects in a big way. But the residual thing, you know, if you want to write or make movies, you have to do it out of a passion, and out of a true desire to to be a creative force. Because if you do it to make money, you're in the wrong business. Anybody who sets out to make money making movies is in it for the wrong reason, and they're not gonna make it

Alex Ferrari 54:33

right. What's that saying? How do you how do you become a millionaire in in the film business? Start with a billion. Yeah. It's, it's, it's so true. And I've had so many so many filmmakers over the years come to me like Well, yeah, you know, I'm gonna make this money and that money I'm like, honey, Sir, this is you. You are so in the wrong you know? Like, do you want to Do you run into this? I mean, I'm sure you've spoken to screenwriters coming up screenwriters and filmmakers over the years? Do you see a lot of that a lot, I call it a lottery ticket mentality where they think the next movie is gonna give them you know that they're going to get Steven Spielberg's eye, and he's gonna come down and do all this stuff, or it's going to hit Sundance, or it's gonna get me an agent that's going to give me a million dollar on my next spec, or do you see that mentality in people you want to,

Mick Garris 55:24

there's still enough of that happening, that it's, it's, it's worth, you know, don't give up a dream if your head if you've been pounding your head against the wall for 20 years and have never sold a screenplay, chances are good, that it may not happen. But then it might, you know, I've just reworked a movie that I wrote, I wrote a screenplay 30 years ago, called Jimmy miracle. And I've always thought it was the best movie idea I ever had. And Spielberg loved it at the time. But it wasn't a movie whose time had come. And it's a period picture takes place during the Depression. And so I thought, maybe I'll write it as a novel. And I rewrite it now and then. But I came up with an idea on how to completely revamp it. And keep all of the elements that made it exciting to me, but gave it new elements that made it even more exciting to me. And almost immediately it's been optioned, and we're taking it out to the studios next week. So you know, it's, you got to keep at it as long as you can stand. But if it's been 20 years, and you haven't been able to do it, then do it. Not, you know, don't live at your mom's house, mowing lawns in the hopes that you're going to make it as a screenwriter, if it hasn't happened for 20 years, go ahead and get your job as a lawyer, you know, finish school and, and do that. But, you know, a lot of times I wrote more when I was working a day job than I do working full time as a writer and filmmaker. But it's something it doesn't cost you anything to be a writer. And you know, it's a great hobby, regardless of whether things get made or not. I've written a lot of spec scripts that have never been made, or optioned. And that's just part of the game. But I get to be a better writer each time I do it.

Alex Ferrari 57:30

Now, there's one other project I wanted to talk to you about, which is I generally don't bring up short films on this on this show. But I mean, you worked on ghost. It was a famous short film, starring the late you're not that well. I mean, quote unquote, short work, starring the late great Michael Jackson. And your collaborator was also the late great Stan Winston. And and Stephen King. And oh, that's right. Stephen King was involved with that as well. So I mean, talk about a trifecta of icons, each of them an icon and you're working. What was it like collaborating with, with Michael Jackson, Steven and, and Stan on this, and the show for which I remember was not released in the States. While we're a long time. Yeah.

Mick Garris 58:24

I think it premiered on Halloween, like, two years after it had been made.

Alex Ferrari 58:29

Because I wanted to watch it. Yeah.

Mick Garris 58:32

It was an incredibly troubled production for a number of reasons, including the obvious ones. But Michael went to Stephen King, he said, I want to make the scariest movie ever because he had so much enjoyed making thriller in which I am a zombie, by the way, oh, I mean, what you should

Alex Ferrari 58:49

have led with that make

Mick Garris 58:52

very delete. But so I was shooting the stand at the time. And King had written a draft for Michael. And he'd recommended me as the director to Michael. And so I met with Michael and we hit it off great. He was very sweet. And so we started production and we shot for two weeks. It was originally going to be the end title song for family Addams Family Values. And once we were shooting, we shot for two weeks and never got to the musical number yet when you work with Michael, you worked on Michael time and it didn't have much to do with a 24 hour clock or even a 30 day calendar. So, you know he was great and hard working but it was really slow and two weeks into the shoot. Michael didn't show up the next day. And suddenly we started hearing about this scandal that had happened that none of us believed because Has anybody who'd worked with him could not believe that this was going on. And, to this day, I don't know what the truth of his of it is. My only experiences with Michael were really good ones, we became friends. But, you know, if he did what it said he had done, it's the worst thing in the world. And if he didn't, it's also the worst thing in the world. But he disappeared. And it turned out he was in Thailand. And then we were going to finish it in Japan and my line producer went to Japan and shipped all of the sets we'd been working on to Japan. And then they were shipped back it, it didn't happen for three years. And then Michael said, Okay, I'm ready. We're gonna do it now. Make it's gonna be great. It's

Unknown Speaker 1:00:48

gonna be fantastic.

Mick Garris 1:00:50

And it's been a very good, very good impression, Bella. Thank you. But I was already scheduled to do the shining with Stephen King next. And so I said, Michael, I can't just keep putting this off. I have a hard start date. And you don't. So I, I think you should talk to Stan Winston, they were friends. Stan is a very was a very good director. He had done pumpkin head at that time. And so I said, you guys are friends. He's doing the special effects. Anyway. You should ask him and he he did. And so I had shot two weeks worth of stuff. Including a lot of the visual effects stuff that stands company did digital domain Stan and Jim Cameron's company. And so Stan took it over and it was great. It was everything but the kitchen sink. It was a 35 minute movie that was originally going to be a seven minute music video at most a 15 minute video, but you know Michael ended up paying for the whole thing ended up costing $15 million the most expensive music video in history. And it was a blast but I would love to seen it through from beginning to end but that just though I wouldn't have been able to do the shining

Alex Ferrari 1:02:12

and I'll tell you I had the pleasure of going to stand studio visiting Stan studio while he was still alive and I didn't get to meet Stan but I got to go they took me through the entire studio and that that board room. Oh my god that boardroom for everyone listening the boardroom had the Terminator the predator an alien every like Tom Cruise's. Let's start from Interview

Mick Garris 1:02:36

with the Vampire all that Christopher Lloyd holding his head. Yeah. Facing stories episode.

Alex Ferrari 1:02:42

That's right. All of that stuff was it was two stories. I remember to two floors of all these things looking down on you. Oh my god. How cool is it to have meetings in here? Lucky, lucky people. Yes, absolutely. Now I'm gonna ask you a few questions. I asked all of my guests. What are three screenplays every every screenwriter should read

Mick Garris 1:03:05

every screenwriter should read well alien to see just how concise it can be. Anything by Preston Sturges to see just what what dialogue can be at its best. And you know, Billy Wilder in an eye all diamond as Sunset Boulevard is a great example. Now, none of those are contemporary. You know, I think some of the Tarantino's writing is amazing. He's not the best speller.

Alex Ferrari 1:03:34

But when you turn to you know, it's it's okay.

Mick Garris 1:03:37

It doesn't matter. Because his dialogue and everything is so great and the ideas are big. And, you know, most people will say, don't write a dialogue pay scene longer than four or five pages. He can give you 15 Great, great pages of dialogue. And he savor every word.

Alex Ferrari 1:03:58

You're in like Inglorious Basterds. I'd like that scene in the in the basement with all the Nazis that that was like 20 minutes. Amazing. 20 or 30 minutes of the movie was just that scene. It's it is it is truly, truly remarkable. Do you appreciate just as as a viewer and as a filmmaker, people and filmmakers and screenwriters who take the swings at bat? They might not always connect, but they take the big swings.

Mick Garris 1:04:25

Absolutely. You know, I think Jordan Peele doing get out was great. And then when he did us, he took bigger swings. They didn't connect as much. But it was great to see him make the attempt to do go beyond what he's already done. And yeah, I mean, obviously my favorite films are where it works in every level. But I love creative. There's is a couple of filmmakers named Aaron Morehead and Justin Benson, who write and direct their own movies and they take big fantastical swings, and they more often than not connect. And it's, it's really fun to see adventurous movies. And, you know, I'm not a fan of franchise movies, particularly within the horror genre. It's a, you know, I want to see somebody, I want to see the next David Cronenberg, you know, somebody whose films are so iconic clastic that they couldn't be made by anybody else.

Alex Ferrari 1:05:28

Right. Exactly. And, I mean, and carpenter, obviously with how that Yeah. And and Well, I mean, the list of things that john has done. Oh, yeah. Yeah, absolutely. Now, what advice would you give a screenwriter trying to break into the business today?

Mick Garris 1:05:45

Write, and write and write and write, and the you need to be represented. But you need to write something that's not just good, but reflects a personality that nobody else has. It needs to be something an agent's taking home 30 scripts every weekend. And most of those scripts, he's not going to get further than five or 10 pages. And you need to galvanize your reader, and make that reader excited that he's reading a movie that not only is really great, but is something he feels an audience will come to see that he's not looking for an art film, although there are great commercial art films, you know, you're talking about a medium that costs millions of dollars to do it, right. And you're not just masturbating with a camera, we're doing something for an audience, not for yourself. Now, please yourself first, and please the audience as well. But if you imbue your writing with your own personality in a personality that stands out from all others, and makes your script, even if it's audacious, even if they don't buy the script, they look at it and go, this is a writer we should meet with who might be right for such and such a project. So it's just do the best that you can in the most original way that you can to differentiate yourself from the other 29.

Alex Ferrari 1:07:13

And then it is it is true that and I think a lot of screenwriters and filmmakers don't understand this is that they need to understand what their secret sauce is. and lean into that secret sauce. Don't try to be Tarantino cuz you're never gonna be Tarantino he's already Tarantino, right? You're never gonna be we really have a Nolan. We already have a carpenter, you can be inspired by them. But you have so but you have to be you have to have that secret sauce. And that's the only thing in the marketplace that nobody else has. Right?

Mick Garris 1:07:42

Yeah, I mean, your main your main target, is to get them to want to keep turning the page. Make your scripts readable.

Alex Ferrari 1:07:56

Excellent, excellent advice. Now, what is the lesson that took you the longest to learn whether in the film industry or in life?

Mick Garris 1:08:04

Well, in life, I think there are still lessons I haven't completely learned. But as far as the film industry goes, I mean, it's always going to be up and down. You can do something huge, like the stand and not work again for three years. You know, same. It's, it's every bit as hard. The second, third, fourth and fifth time out is the first time maybe the wheels have been greased a bit in that people know who you are or know your work. But you have to keep proving yourself and you can't rest on your laurels because those were out real quick.

Alex Ferrari 1:08:43

And finally, three of your favorite films of all time. Okay. Dead Ringers. Oh, great. Cronenberg. Yes. Great writer Frankenstein. Yes. And Raiders. avastar. nice combination. That's a good that's a good movie night. That is a good movie night. They'd have nothing in common. Yeah. Now, where can people find watch your show and then consume your content, sir.

Mick Garris 1:09:15

Okay, my podcast post mortem with Mick garris is on Apple podcasts and every other podcast app around. We interview do interviews every other week. And on the alternating weeks, we do post mortem ama where you can ask Nick anything, and we solicit questions. I'm on Facebook at post mortem with Mick garris Mick garris pm on Instagram and on Twitter. And we'll keep things alive that way all the time. You'll know what's coming and when we're asking for questions from the audience,

Alex Ferrari 1:09:50

and all that stuff. And I will put that all in the show notes. Mick, thank you so much for taking the time for the show and dropping your knowledge bombs on My tribe today so I appreciate

Mick Garris 1:10:02

all right, always a pleasure. Thank you

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

Please subscribe and leave a rating or review by going to BPS Podcast

Want to advertise on this show? Visit Bulletproofscreenwriting.tv/Sponsors