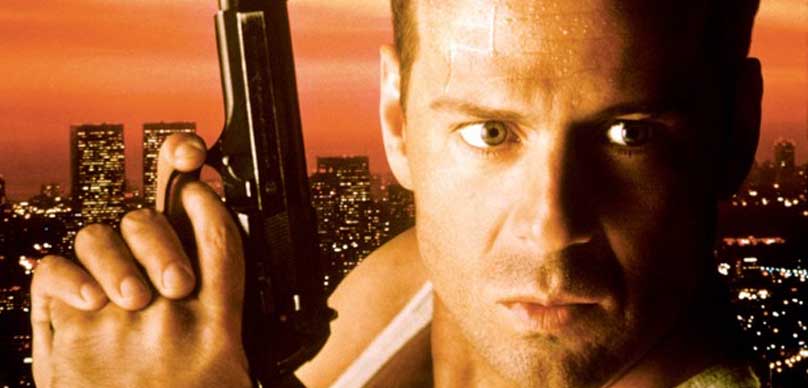

BUTCH CASSIDY AND THE SUNDANCE KID (1969)

Screenplay by William Goldman – Read the screenplay!

ALL THE PRESIDENT’S MEN (1976)

Screenplay by William Goldman – Read the screenplay!

MARATHON MAN(1976)

Screenplay by William Goldman – Read the screenplay!

MAGIC(1978)

Screenplay by William Goldman – Read the screenplay!

“William Goldman is, by far, one of the most popular storytellers of our generation,” says Sean Edgar, an author.

Stated above is one the millions of great testimonies people around the world have to say about the iconic writer, William Goldman. Though his name may not ring a bell with people who are not the within the entertainment industry, but it is definitely a household name anybody who works within the industry.

William Goldman, one of the most successful and prolific novelists, playwright and screenwriter ever, was born on August 12,1931. His fiction novels became popular in the 1950s and after then he ventured into the into the world of writing screenplays, for which he won so many prestigious awards including two Academy Awards(firstly, for the western Butch Cassidy and Sundance Kid in 1969, and then for All the President’s Men in 1976)

His books on the craft of screenwriting are legendary and a must-read for any screenwriter.

- Adventures in the Screen Trade: A Personal View of Hollywood and Screenwriting – Amazon

- Which Lie Did I Tell?: More Adventures in the Screen Trade – Amazon

- Four Screenplays with Essays – Amazon

- The Big Picture: Who Killed Hollywood? and Other Essays – Amazon

William Goldman was born into a Jewish family in Chicago. His father, Maurice Goldman, was a businessman whose successful business eventually went south due to his alcoholism. Maurice later committed suicide when William was still in high school. Consequently, William and James, his brother, were left alone to cater for their mother, Marion Goldman, who had a hearing impairment.

William Goldman obtained his BA degree from Oberlin College in 1952. Afterward, he joined the army as a typist and was sent to the Pentagon as a clerical officer in 1954. After he was discharged as a corporal from the army, he went to Columbia University for his master degree. Meanwhile, in his spare time, he resorted to doing what he loved the most – writing short stories – and strove to get them published.

According to William Goldman himself, he said he began writing after he took a creative writing course at his alma mater. It should be noted that, initially, William did set out to be a poet and novelist but not a screenwriter, which he was later well-known for across the globe today.

Before he started his career as a screenwriter, William Goldman had had five novels in prints and three plays produced on Broadway. His debut novel was TheTemple of Gold, which was a success. Marathon Manwas the thriller he wrote after the death of his first agent, prior to which he focused on serious literary works.

His writing career to a sharp turn in 1964 when an actor, Cliff Robertson commissioned him to adapt the screenplays for Flower for Algernon, which was renamed Charleyand for which Cliff won the Academy Awards for the Best Actor. Having seen the job well-done by Goldman, Cliff had him rewrite Masquerade, which was Goldman’s very first screen credit.

William Goldman spent eight years researching Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, his first original screenplay and sold it for a record $400,000 in the late 1960s. Afterward, he used several of his works as the basis for his screenplays such as the Princess Bride, All President’s Men and so on, except his novel No Way to Treat a Lady which was translated by somebody else. One of William’s most popular un-produced works is a pirate adventure, The Sea Kings but it was scrapped because the budget was way too high.

One of the greatest creative confessional ever written about the entertainment industry is was Goldman’s Adventures in the Screen Trade, which opening sentence

“Nobody knows anything”

was the most famous personal quote line ever written by Goldman. The idea of the title actually came from Dylan Thomas’ collection of stories titled Adventure in the Skin. The book was an interesting exposition on how the Hollywood entertainment industry works and contains virtually everything an intending writer needs to know about the industry. The book explained how the success of a film is affected by the stars, the producers, the writers and other professional players associated with.

It also tells the story of each film in the life of the great screenwriter, William Goldman and then finally, the book went on to give a step-by-step, comprehensive exposition on how one of William Goldman’s masterpieces, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, was made with a full presentation of the screenplays. The book was actually about Goldman’s feelings about his business. He wrote the screenplay of the Butch and Cassidy and the Sundance Kid while he was teaching creative writing in the Christmas vacation of 1965-1966. All studios he showed it to rejected it except one, the 20thCentury Fox, which finally accepted it.

Then the 20thCentury Fox embarked on the project of the filmmaking. The filmmaking was directed by the George Roy Hill whom William Goldman considered to be the greatest and most prolific director he has ever worked with. The movie stands out as Goldman’s biggest success commercially ever. After the production of the Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid film, he began – perhaps motivated by the success – to more novels and screenplays.

Often, he would tell his daughters, Jenny and Susanna, bedtime stories and on one fateful night, he asked them what the title of the stories they wanted him to tell them, and then one said “Princess” while the other said “Bride”. And that was how he got the title for his superb novel, the Princess Bride in 1973 and shortly after then, he wrote the screenplay for the novel. According to him, that is the only novel really likes. Perhaps the likeness was a kind of emotional attachment to the work which would be, most likely, as a result of the anguish of mind he experienced because the work took an unusually long time.

William Goldman disappeared from the limelight in the entertainment industry for almost a decade after writing to Mr. Horn in 1979. This was, definitely, not because the stream of Goldman’s creativity has dried up but because the self-financed producer, Joseph E. Levine, he was in a screenplay writing a contractual agreement with, could not finance the budgets of the filmmaking, so none of these works was produced during those years.

On the other hand, Goldman too made a lot of efforts personally to get other studios and producers to help him produce some of them, but that too was to no avail. Meanwhile, he continued to write several other books, one of which was Adventure in the Screen Trade which finally became a best seller.

Fortunately, he was able to secure a job with Creative Artists Agency (CAA)in 1986 and within a month he was offered the rights to adapt An Invisible Man, memoir authored by H. F. Saint and, luckily for him, the film was produced.

However, his first real comeback movie was in 1987 when one of his novels, the Princess Bride was produced. In 1990, he was also commissioned by Rob Reiner, director/producer, to write the screenplay for Misery which was adapted from a novel authored by Stephen King. He continued to write popular screenplays in the 1990s, namely Maverick in 1994, The Chamber in 1996, the Ghost and the Darkness in 1996, and Absolute Power in 1997. He also co-authored the screenplay for the General’s Daughter with Chris Bertiloni in 1999.

At the dawn of the new millennium, another of Goldman’s memoirs was released titled Which Lie did I Tell? It reflects the usual honest, down-to-earth style characteristic of Goldman’s literary works. In the book, he explained all a writer need to know about the screenwriting business and how to thrive in the business.

Goldman is prolific not only in the art and craft of screenwriting but also in novel writing. The following are some of his many works:

Theatre: Blood, Sweat and Stanley Poole (with his brother James Goldman), Misery, A Family Affair.

Screenplays: Masquerade, Harper, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, The Hot Rock, the Stepford Wives , All the President’s men, A Bridge Too Far, Misery, Year of Comet, Chaplin, Indecent Proposal, Last Action Hero, Maverick, Malice, The Chamber, Dreamcatcher, Wild Card, Absolute Powers, The General’ Daughter, Wild Cat, Dolores Clairborne, Heart in Atlantis, Twins, The Ghost and The Darkness etc.

Novels: the Temple of Gold, Your Turn to Curtsy, My Turn to Bow, Soldier in the Rain, Boys and Girls Together, No way to Treat a Lady, The Thing of It Is…, The Princess Bride, Magic, Marathon, Tinsel, Control, The Color of Light, the Silent Gondoliers, Heat, Brothers, Father’s Day, Control

Non-fiction and memoirs: the Season: Candid Look at the Broadway, Adventures in the Screen Trade, Hype and Glory, Which Lie Did I Tell? Wait Till Next Year, the Picture: Who Killed the Hollywood etc.

Short stories: Something Blue, Rogue, the Ice Cream Eat, Till the Right Girl Comes Along, Da Vinci, the Simple Pleasures of the Rich etc.

Almost 50 years career as a professional writer, Goldman has won awards to his name including two Academy Awards(both for Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid and All the President’s Men), two Edgar Awards, he also won the Laurel Award for screenwriting Achievement in 1985.

William Goldman is indeed one of the greatest American screenwriters of all time.