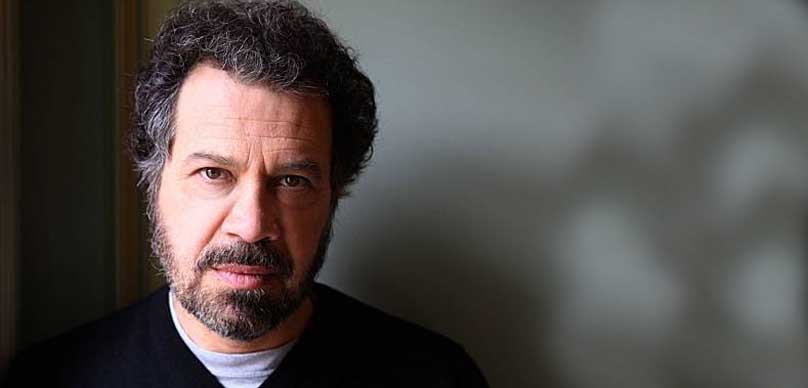

We have been on a major roll lately on the podcast and this episode keep that going in a big way. Our guest on the show today is writer, producer, and director Edward Zwick. Edward made his big shift from his childhood passion of theater to filmmaking after working as a PA for Woody Allenin France on the set of Love and Death. He then moved to California in the summer of 1976 and has since forged a respected name for himself in Hollywood.

Edward Zwick is a multiple Academy Award, Golden Globes, and BAFTA award-winning director, writer, and producer.

Faced with the fear of going to law school during his first five years in the industry if filmmaking didn’t work, Zwick cards turned and launched him into projects that are now some of the most critically and commercially acclaimed in the business. His work spectrums the comedy-drama and epic historical genres. You can see just some of the films he written and directed below.

About Last Night, Edward’s directorial debut was about aman and woman who meet and enter a committed relationship for the first timedespite their personal problems and the interference of their disapproving friends.

He next tackled his first historical drama, and definitely not his last, the Oscar winning Glory.

This is the exceptional story of America’s first unit of African American soldiers during the Civil War and the young, inexperienced Northerner who’s given the job of training and leading them. Based in part on the actual letters of that young officer and brought to life with astonishing skill and believability.

Legends of the Fall: This epic romance follows a man’s fight to come to terms with himself and a family struggling to preserve its simple way of life. Taken from Jim Harrison’s popular Novella, LEGENDS OF THE FALL tells the story of three brothers and the beautiful, compelling young woman who irrevocably changes each of their lives.

Courage Under Fire: A soldier discovers how elusive the truth can be in this first major film about America’s role in the Gulf War. Lt. Col. Nathaniel Serling (Denzel Washington) was the commander of a unit during Operation Desert Storm who mistakenly ordered the destruction of what he believed to be an enemy tank, only to discover that it actually held U.S. soldiers, including a close friend. Since then, Serling has been an emotional wreck, drinking heavily and allowing his marriage to teeter on the brink of collapse.

As a means of redeeming himself, Serling is given a new assignment by his superior, Gen. Hershberg (Michael Moriarty). Capt. Karen Walden (Meg Ryan) was a helicopter pilot who died in battle during the Iraqi conflict, and the White House has proposed that Walden be posthumously awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Serling is asked to investigate Walden’s actions on the field of battle, but he quickly discovers that no two stories about her are quite the same; Ilario (Matt Damon) says Walden acted heroically and sacrificed herself to save the others in her company, while Monfriez (Lou Diamond Phillps) claims she was a coward who was attempting to surrender to enemy troops.

Meanwhile, reporter Tony Gartner (Scott Glenn) is hounding Serling, trying to get the inside story on Walden and on Serling’s own difficulties. Matt Damon lost 40 pounds to prepare for his role in Courage Under Fire, which resulted in a potentially life-threatening illness for the young actor.

The Siege: When a crowded city bus blows up in Brooklyn and a campaign of terror begins to make it’s bloody mark on the streets of New York, it’s up to FBI special agent Anthony “Hub” Hubbard (Denzel Washington) and U.S. Army General William Devereaux (Bruce Willis) to find out who’s responsible and put an end to the destruction. Together, they face explosive danger at every turn when they team up towage an all-out war against a ruthless band of terrorists.

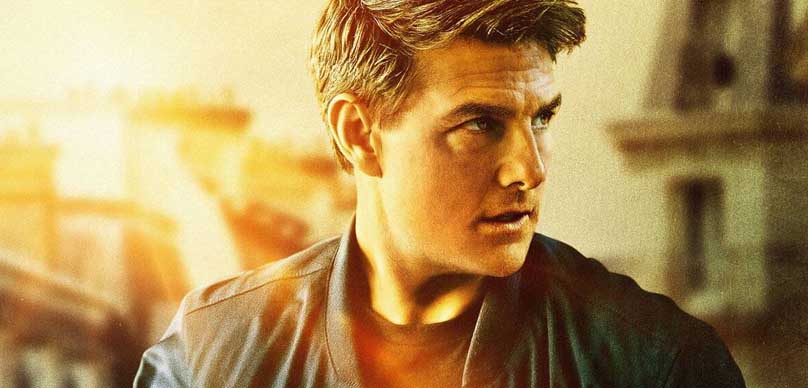

The Last Samurai: Tom Cruise stars in this sweeping epic set in Japan during the 1870s as Captain Nathan Algren, a respected American military officer hired by the Emperor of Japan to train the country’s first army in the art of modern warfare.

As the Emperor attempts to eradicate the ancient Imperial Samurai warriors in preparation for more Westernized and trade-friendly government policies, Algren finds himself unexpectedly impressed and influenced by his encounters with the Japanese warriors, placing him at the center of a struggle between two eras and two worlds, with only his own sense of honor to guide him as The Last Samurai.

Blood Diamond: An ex-mercenary turned smuggler (Leonardo DiCaprio). A Mende fisherman (Djimon Hounsou). Amid the explosive civil war overtaking 1999 Sierra Leone, these men join for two desperate missions: recovering a rare pink diamond of immense value and rescuing the fisherman’s son, conscripted as a child soldier into the brutal rebel forces ripping a swath of torture and bloodshed across the alternately beautiful and ravaged countryside.

Jack Reacher: Never Go Back:Ex-military investigator Jack Reacher (Tom Cruise) leaps off the pages of Lee Child’s bestselling novel and onto the big screen in the explosive thriller the critics are calling “taut, muscular, gruff and cool”*. When an unspeakable crime is committed, all evidence points to the suspect in custody who offers up a single note in defense: “Get Jack Reacher!” The law has its limits, but Reacher does not when his fight for the truth pits him against an unexpected enemy with a skill for violence and a secret to keep.

Edward even won the Academy Award® for producing Shakespeare in Love.

Shakespeare in Love’ showcases a young Will Shakespeare as the up and coming playwright of the time, but he has been disastrously struck by the bane of the writer’s life – writer’s block. His comedy “Romeo and Ethel, the Pirate’s Daughter” isn’t going anywhere and the playhouse is under threat of closure.

What Will needs is a muse, and she appears in the form of the beautiful and betrothed Lady Viola. The path of true love does not run smooth for Will, but the joys and tragedy of his own life find their way onto the page in a moving, witty and spellbinding tale.

The list goes on. Edward has had a remarkable career so far and still has much more to give. Speaking to Edward was like sitting in my persona filmmaking masterclass. We discuss ho he made the jump from a low budget comedy to epic historical dramas, his creative process, navigating Hollywood, directing some of the biggest movie stars in the world and much more.

Prepare to take notes on this one tribe. Enjoy my conversation with Edward Zwick

Right-click here to download the MP3