Robert McKee, A Fulbright Scholar, is the most sought after screenwriting lecturer around the globe. He has dedicated the last 30 years to educating and mentoring screenwriters, novelists, playwrights, poets, documentary makers, producers, and directors internationally. Those who have learned from McKee have called him “the Aristotle of our time” because of his insight into the substance, structure, style, and principles of the grand art of story.

Peter Jackson (writer/director of The Lord of the Rings Trilogy, The Hobbit) has lauded him as “The Guru of Gurus.” For the writers of Pixar (creators of Toy Story 1, 2, & 3, Finding Nemo), McKee’s Story Seminar is a rite of passage. Emmy Award-Winner Brian Cox also portrayed McKee in the Oscar-nominated film Adaptation.

McKee’s former students include over 60 Academy Award Winners, 200 Academy Award Nominees, 200 Emmy Award Winners, 1000 Emmy Award Nominees, 100 WGA (Writers Guild of America) Award Winners, 250 WGA Award Nominees, and 50 DGA (Directors Guild of America) Award Winners, 100 DGA Award Nominees.

A winner and nominee of BAFTA for his popular Channel Four series Reel Secrets, McKee also wrote and hosted 12 episodes of BBC’s Filmworks series. He was profiled by Bob Simon of 60 Minutes for CBS news.

McKee’s articles on Story have also appeared in hundreds of newspapers and magazines around the world including Harvard Business Review, The Wall Street Journal, Vanity Fair, The New Yorker Magazine, Swiss Business Magazine, Sueddeutsche Zeitung, CBS Morning News, BBC, Channel 4 in UK, RAI (Italy), CBN Weekly News & Morning Glory (China), MBC TV, KBS & Arirang TV, Korea Times (South Korea), Kiev Weekly, Kultura Moscow, all major TV, Radio and/or newspapers of Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Germany, France, India, Israel, Mexico, New Zealand, Portugal, Russia, Turkey, Singapore, South Africa, Sweden, and Switzerland and given seminars in all of the above countries.

Since 1984, more than 100,000 students have taken McKee’s courses at various cities around the world: Los Angeles, New York, London, Paris, Sydney, Toronto, Boston, San Francisco, Helsinki, Oslo, Munich, Tel Aviv, Auckland, Singapore, Madrid, Beijing, Shanghai, Barcelona, Lisbon, Malaga, Hamburg, Berlin, Johannesburg, Rome, Stockholm, São Paulo, Santiago, Buenos Aires, Bogota, Beijing, Brussels, Rio de Janeiro, Moscow, Seoul, Istanbul, Hyderabad, Mexico City and many cities regularly.

McKee continues to be a project consultant to major film and television production companies such as 20th Century Fox, Disney, Paramount, & MTV. In addition, Pixar, ABC, BBC, Disney, Miramax, PBS, Nickelodeon, Paramount, GLOBOSAT, MNET and other international TV and Film companies regularly send their entire creative and writing staffs to his lectures.

His new book is Action: The Art of Excitement for Screen, Page, and Game.

ACTION explores the ways that a modern-day writer can successfully tell an action story that not only stands apart, but wins the war on clichés. Teaming up with the former co-host of The Story Toolkit, Bassim El-Wakil, legendary story lecturer Robert McKee guides writers to award-winning originality by deconstructing the action genre, illuminating the challenges, and, more importantly, demonstrating how to master the demands of plot with surprising beats of innovation and ingenuity.

Topics include:

- Understanding the Four Core Elements of Action

- Creating the Action Cast

- Hook, Hold, Pay Off: Design in Action

- The Action Macguffin

- Action Set Pieces

- The Sixteen Action Subgenres

A must-add to the McKee storytelling library, ACTION illustrates the principles of narrative drive with precision and clarity by referencing the most popular action movies of our time including: Die Hard, The Star Wars Saga, Dark Knight, The Matrix, and Avengers: Endgame.

Also join Robert McKee’s Legendary STORY Seminar LIVE in Los Angeles, New York & London

In an intense 3 days, Robert McKee teaches the substance, structure, style and principles of Story. Learn how to apply classical story design – the kind that has resulted in masterpieces of all kinds – to your own cinematic, theatrical or literary premise.

👉 McKee STORY Seminar (10% OFF – Coupon Code: HUSTLE)

Enjoy my conversation with Robert McKee.

Right-click here to download the MP3

LINKS

- Robert Mckee – Official Site

- Action: The Art of Excitement for Screen, Page, and Game

- Robert McKee’s Legendary Story Seminar – Los Angeles Oct 6-8 (10% OFF – COUPON CODE: HUSTLE)

- Book: Character: The Art of Role and Cast Design for Page, Stage, and Screen

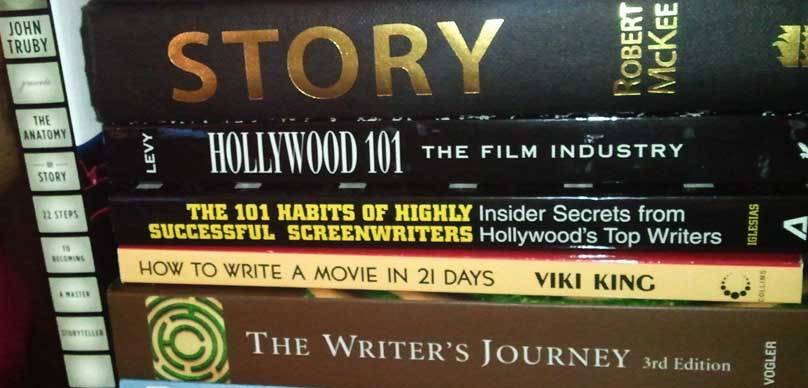

- Book: Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting

- Book: Dialogue: The Art of Verbal Action for Page, Stage, and Screen

- FREE AUDIOBOOK VERSIONS FO ALL OF ROBERT MCKEE’S BOOK HERE

- BPS 125: The Art of Story, Dialog, and Character with Robert McKee

SPONSORS

- Bulletproof Script Coverage– Get Your Screenplay Read by Hollywood Professionals

- Audible– Get a Free Screenwriting Audiobook

Robert McKee 0:00

Because whoever has it has power. And so the hero can get the MacGuffin back. And then the villain takes it back again and amending it, they can exchange this, they can lose it, they go searching for it.

Alex Ferrari 0:12

This episode is brought to you by Bulletproof Script Coverage, where screenwriters go to get their scripts read by Top Hollywood Professionals. Learn more at covermyscreenplay.com I'd like to welcome back to the show returning champion, Robert McKee. How are you doing, Robert?

Robert McKee 0:30

I'm great, Alex and you?

Alex Ferrari 0:32

I'm doing very good. Thank you so much for coming back on the show. Our last conversation, as you might might have known did very well, people love, love you and love what the way you approach story and dialogue and character. Now, in this episode, we're going to talk about your new book, action, which I when when I when you guys reached out to me, it was like, Oh, my God, he's got another book, I used to go, he's going crazy. He's just releasing books left and right. I remember story was like, for a long time, the only book and then now you're popping them out left and right.

Robert McKee 1:03

You know, in mice, my method is to teach something before I write about. And I do that, because I want to do the questions. And, and then I have to find the answer. And so I when I taught enough about dialogue. I wrote a book when I first been teaching about character for decades, I wrote a book. And and now in action, I've been doing seminars, and webinars on action for some time. So, so yeah, and, and in fact, as we speak, I am busily writing story two, oh, my but chapter three. And so it's been 25 years since I wrote story. And I learned a lot in those 25 years. And so I'm going to do a whole new version of story and come in with a very different perspective and approach. The same fundamentals. But anyway, I keep writing. I don't know what else to do.

Alex Ferrari 2:26

I mean, might as well just keep going, my friend, well, you're doing a service for this for screenwriters and storytellers around the world with your work and, and that's why I love to highlight what you're doing here on the show. So, my very first question is what is principal versus presentational genres in action?

Robert McKee 2:45

Ah, good. One is content and the other is form. Okay. So the principal genres give you content. And so you have action, the content is life and death. Then you have love stories, for example, the content the value there, of course, is love hate, you have family gross domestic grows there, the content and unity versus breakup, and, and undergoes savvy, these principle genres, crying, where the content is justice, injustice. And so you have these principles drawn into about 10 or 10 or so of them that I list. And they give you the value at the heart of the story, they give you the principal characters, they give you the principal emotion, you're trying to express and, and cause people to feel, and they give you the core scene, the essential turning point of the whole story. And so now that is his content, but now you have to express it. So now you you have to present that story. And so you could tell it, realistically, that's a presentation. Or you can tell it as a fantasy. You could put it in the contemporary setting, or you could put it in a futuristic setting or in history. You could sing and dance it as a musical and on a goat. And so you have all these various styles of presentation. And, and there's a dozen or so those and so, in principle drowner these are the rock this is the core storytelling these are the great forms the the modern epic The ancient epic consumer, these are the 1000s of years old content, what we tell stories about the course there are great principal content, genres that are about human change. And so the there are stories about the changing morality of a character. We as they move from immoral, immoral and redeem themselves, where they, and they moved from moral immoral and the damage themselves. If there's stories of characters, evolving as human beings in a positive way, becoming more complete realizations of their human potential, or you have stories for people, and just drug drugs or whatever, destroy their, their humanity. And so you have a half a dozen of these primary genres about character change. And then another character swap genres about changing the outer circumstances of a character's life, as we do in, in crime stories, and the love stories and so forth. Those are the foundations. And, and, and action is one of those action is a principal primary genre. And there's lots of ways to do action, you can do it as a fantasy, you can do it in sci fi, you can do it in realistically, whatever in history, etc. All of those presentations are, are at your disposal as a as an action writer. She's got a lot of choices, a lot of choices. And all of those primary genres or principal genres can be merged.

Alex Ferrari 7:09

Like something like Braveheart has a lot of those genres inside of that it's a romance is a love story. It's action. It's a revenge film, there's so many things in Braveheart.

Robert McKee 7:20

Yeah, it's, it's frequently merge a love story with a with an action story, where you know, the love interest story gets in the way, causes causes the protagonist that make choices you never would have had to make otherwise. And, and but, and crime, of course, crime and action get merged a lot. thrillers and action get merged a lot. And so see, all those principal genres, and they get can be mixed and merged. Mixed, meaning you cut back and forth between the genre merge means to to cause one another. And so the reason for the thriller causes you to get into action. And so that, you know, the variety that is, is infinite.

Alex Ferrari 8:19

It's endless, without question. Now you talk, you talk about the four core elements of action. Can you discuss a little bit about those core elements?

Robert McKee 8:29

Yeah, if you've seen all the principal genres have four cores. You have a core cast? What is the essential past minimal essential cast? So in a love story, is that two people we got lovers, right. And family story you got, you know, usually husband, wife and kids, right? In an action story, you've got a hero, a villain, and a victim. And those three are essential. If you eliminate the victim, there's no point than the hero and villain playing it out nothing's instead. If you eliminate the hero, then it's a thriller, because if the victim has to survive, and that's not heroic, and so you have an CMO of three core characters, then you have a core value and an action. It's life and death. Justice, injustice is the value of a crime story. Okay, but justice injustice is irrelevant. In Action. The core value of action is life and death. Whether or not laws are broken better kept doesn't matter. GN a quarterback. You have a quarry event and the quarry event in action. The most difficult scene, by far to write is the hero at the mercy of the villain weaponless defenseless back to the wall, totally at the mercy of the overpowering villain. And from a position of complete helplessness, at the mercy of the villain, somehow, the action hero has to find the resources to turn the tables on the villain and in that scene come out on top, locally at the mercy on top, and that it will that'll break your back trying to figure out their greed that seemed. So they have core values, the core value of core characters, core event, and the core emotion. Why do you want people to feel when you're writing in any of those principal genres, and in action, the emotion you want them to feel is excitement. A thriller is full of tension. Right? Because thrillers are all about darkness on figuring out who can you trust? What's really going on here? What do they want? What are they got an image all these questions, and then and you're lost in the labyrinth of a thriller. But in action, though, he's, it's there. It's happening right in front of you. And so what you're trying to get people to feel is excitement. That's why I put it in the subtitle of the book, it's not an action, the art of excitement. You try and create that that's an you know, that's a wonderful experience. And really feel the excitement of the ash. And not boredom, not you know, not mystery and excitement. So you know, the four course and and each of the principal genres that are listed in the first chapter of the book, in order to orient the the reader to the to the action. Each of those genres has those four courts. You all have Gore cast Corey motion, Cory bed.

Alex Ferrari 12:56

So when you were talking, I was I was thinking of this scene in Terminator two, which illustrates everything that you're talking about where, where you got Arnold fighting of obviously a much more superior villain, which is a t 1000. And to the point where the He's helpless against them literally. They he gets stabbed, spoiler alert, get stabbed with a giant metal rod, and he's stuck there and everyone thinks he's dead. Yes. And then he has to come back and save the victims, which is Linda Hamilton and and John Connor. Yeah, so Sarah Connor and John Connor. So in that ultimate in as I'm talking about it, I'm starting to get chills. Because it's playing in my head. It's, that's that's how good James Cameron is when he

Robert McKee 13:42

Acts out and that was that was fantastic. And they and Terminator films are wonderful. And the that is that is that quarry meant the hero at the mercy of the memory. If I tell you that action of questions is wondering is there relative var? Because I teach other genres, you know, comedy so forth. is accurate in the in the greatest demand? Not just not just in films, but in games. Right. Even more engaged in Yeah, who knows? And of course in long form television, and novels, the action genre, is it because of that, I think because of the tremendous pressures in society today. To get into an action story is a great pleasure.

Alex Ferrari 14:58

So like I was saying that that If you look at the top 10, even the top 20 biggest blockbusters of all time, even the animated ones have action in it. They all have action and then a perfect example is the latest. You know, the the Messiah that is Tom Cruise. With. With Top Gun Maverick. Yeah, I mean that movie. Did you get a chance to watch Top Gun? Oh, yeah, sure. I mean, it is. I was on the edge of my seat. I was bawling. I was crying. I was excited. That's the initial excitement.

Robert McKee 15:34

Yeah, it was great. It was just great. Those sequences OSHA fighters. Fantastic stuff. So so, you know, if somebody wants to, to find success in Hollywood today, writing action is the the widest open door there is. But it's also an ask. Why is that? It's so hard. For two reasons. One, it's been done to them. Yep. And so and the writer has to win the war on cliches.

Alex Ferrari 16:22

Can you dive into that a little bit, because a lot of people don't understand that. I'd love you just to talk a little bit about cliche.

Robert McKee 16:30

A cliche, is a great idea that someone had 100 years ago, litter. Okay, great idea. One of the first movies of all time 1903 was a was a chase across the desert, you know, stagecoach chick, whatever, right. And it was a great idea. People loved it. And, and because it's such a the the original was such a wonderful idea. It has been copied and copied and repeated and done, and done and done and done for decades. until everybody has seen it. So many times. That even though originally it was a great idea, it's now the most predictable and boring choice. That's a cliche and action. Because we have told action stories before the movies, I mean, you know,

Alex Ferrari 17:40

The Iliad.

Robert McKee 17:42

Exactly. It's one big log action piece, right. And so because we've been telling action stories for literally 1000s of years, all of these great ideas have been collected into what we, you know, we call cliches. And, in we know them all, we've seen them too many times. And therefore they are instantaneously boring. Because they sit there thinking I've seen all this before. So despite decades, if not centuries of a certain genre, the contemporary writer has to go to battle against these cliches they've got to do what kind of distort the genre requires. We've got to create a villain, not the kind we've ever seen before. They got to create a hero, but not the kind we've ever seen before. They have to create a victim but not the kind we've ever seen before that are put that victim in jeopardy, but not the way we've ever seen it before. We got to rouse that hero to action, but not the way we've never seen before. And, and and all of the strategies and tactics of action have to be worked with, but in fresh, fascinating ways. And the most difficult of all, is the Euro at the mercy of the better. How are you going to turn the tables from the position of helplessness that we've never seen before? And if so, make them take on action. Write a Screenplay write a novel or a game and bring it to the point of hero at the mercy of the villain and have that hero turntables out of the building in a way that is true to the characters, true to the setting. But unlike anything we've ever seen in quite that way before, if you will, you will, the novel will sell your script will be bought, your game will be played. I mean, because that, for those of us who love action, that is what we are looking for, to build that story to that great moment and have it it's happened in a way that we didn't see coming. But when it happens, it makes beautiful sense of surprise, with a rush of insight. So I wrote action to give writers the understanding of the genre that they need in depth. So that they tackle it. They don't they they don't just leave elements out. By mistake. They know what that what the drama requires. And I give them tons of examples. So they see how it's been done wonderfully and sometimes badly in the past. And then I you know, your push instead got it.

Alex Ferrari 21:33

Go with God. Let's see what you. So there's two things that were as you were talking came to mind, one movie that turned cliche on its head while poking fun at cliche was scream, which is an action horror thriller in a way and it was brilliantly done. But the definition of cliche of a more modern time is a film like diehard. When diehard came out, there had never been a terrorist takeover. Or if they had it was not like diehard. And then now and then now diehard and a plane diehard about diehard stadium diehard. It's everywhere now. So now it's a constant cliche.

Robert McKee 22:14

Cliche, because they are one was superbly original. It captured all of the great structure of the nature of the genre, it executed everything. But in a way you didn't see coming and didn't care, you were all caught up and destroyed. And the Mercy scene is the greatest mercy. Wives are the greatest verses scenes in action. And so then, so then it gets repeated. And it becomes a cliche.

Alex Ferrari 22:51

Right very much like what 48 hours did and Lethal Weapon did, which was the buddy cop movie. Yeah, that died down Jesus. I mean, how many movies? Since those movies came out?

Robert McKee 23:05

Well, it's easy to see why because I mean, writers are under a tremendous pressure to create something that people want to see. Investors are under tremendous pressure to make sure that their investment makes a profit. And, and so when you you know, when you can go into a producer's office and say, you know, it's it's diehard, on a runaway train, or whatever it is, well, we've had runaway trains, with all new diehard et cetera, okay. And, and you put it in certain boxes for them, then they know what you're trying to do. Right. So then they read the screenplay and see if you did did it in a fresh way. And if you turn the cliches upside down if you did it with with enough originality, that people aren't going to sit there going on it's it's dire and and a trade offs, you know, before winning the war on cliches is a hell of a thing because we are so prolific in our storytelling. And when we think about it, people today, between going to the movies watching TV at night, reading novels that they do playing games, they do spend almost as much time inside of fiction as they do inside of reality. In the 19th century, for example, how much time did the average middle class person spent in fiction per week? Well, if they were a reader, they might might read Oh my one hour a day,

Alex Ferrari 25:01

Hour to a day for like, Yeah,

Robert McKee 25:03

I'd say that's a lot. But let's say an hour a day. And, and if they lived in a city with have enough size that was a theater, where they could go to the theater once a month, that's two hours. And so you know, in a month's time, they might expand all together, if they really have 30 hours in fiction. People do that now, every week. And so the amount of time people spend in fiction has quadrupled, maybe tenfold. And so. And so with all of that storytelling, all of these elements get repeated. And they become cliches.

Alex Ferrari 26:00

You know, what's funny, I have my daughters. I have young daughters, and I watch them watch television with me sometimes. And it's so fascinating that they're so young, but yet they're able to like, that's the bad. That's the real bad guy over there. Or that's, and they're calling it, and I'm like, how are they? They are so

Robert McKee 26:20

They're calling right?

Alex Ferrari 26:22

Yeah, they're calling they're calling it almost all the time. Perfectly. Right? They're going, that's not that. No, it's the other guy. He's the real bad guy in you. And I could probably look at that movie and go, yeah, it's obvious. It's gonna be this guy. I mean, it's we've seen it a million times. But they're like, young, they're very young. And they're calling it so can you imagine when they're 2030 years old? How much content story they've gone through much more than I did. definitely much more than you did. Over, you know, as we grew up, so it's so much more difficult for the writer to surprise. That's why when something that does come out that is new and fresh, people lose their minds, and they're like, Oh, I can't see that.

Robert McKee 27:04

That's right. And that's why it's so difficult. people resort to spectacle.

Alex Ferrari 27:10

Which, which is and I want to ask you something about spectacle, because I think there's a lot of spectacle in Hollywood right now. Do you believe that? The success of like the Marvel films, which are obvious, obviously taken over the theatrical experience, pretty much if you take Marvel out of Marvel Star Wars, and Harry Potter out of out of the theaters for the last 10 years, 1015 years, we wouldn't have a theatrical business. Well, so is it because there's we've seen spectacle before. And there's been bad spectacle. I mean, really, a movie like battleship. I remember years ago, that was all spectacle, all spectacle, or Transformers 72, which is all spectacle and people are like, you know, I've seen a transforming robot before I need more. What is it about the Marvel films that is connecting with audiences? Because it's not I don't believe it's just spectacle, there has to be something deeper, I'd love to hear your thoughts.

Robert McKee 28:06

Well provided spectacle, but the, the, the visual artists who are working on those films have imaginations and techniques to execute those imaginations that are really superior to anybody else. They have simply gone up. It's like a sports team. They've gone out and got the best players at every position available in the league. And so they're gonna win every game 37 They're not right. So it is spectacle in in that day, they just do it better. So that, you know, there's you see that it spectacle on one level, that is create curiosity. It's not about outcome. How will this turn out? Because we know those stories, right in your daughters know how it's gonna turn out. Okay? It's, it's, how will they do it? In order for it to turn out. And so the curiosity is about the execution of the action. And if the execution of the action is fresh, original, and really, I believe and stunning to watch, and the music and the sound and all the rest of it, and the editing, all goes together if it creates a spectacle of a quality that we've never seen before. They can do the same old thing but they Do it in a whole new way, or in a way that is more impactful visually than you've ever seen before. So it's still doing. And that's why it's it's very successful. They've just it's challenged. Because it's not as if spectacle has no quality it of course it does. And they had no importance. Of course, that's right. I mean, Aristotle listed all the six elements of the story and spectacle was the last one. And he said the least important, but it's on the list.

Alex Ferrari 30:39

Top Gun Top Gun without those fighter sequences? Exactly. It's a fun movie, I guess. But

Robert McKee 30:47

Well, you see in the action genre, you got to take spectacle and elevate it up. Yeah, it's not number six, if number six from aerosol point of view in the theater 2500 years ago. But now, you know, it's, it's, it's, I don't even know, like, number three on Netflix. Me, you still have events to tell a great story. Character, you still have to have great characters. But then in action, that those events with those characters have to be executed. And I'm fed back that fantastically brilliant way. Surprised, surprising, pleasing. And so inaction. Spectacle has a lot of value. And, and so but you know, people go to the Marvel games, because they know that that will be a visual treat. And at hopefully, they'll do the same thing we've always seen in a whole new way. But then we'll at least don't express it in a whole new way. And so it's snobbish to look down your nose at spectacle and say, well, it's your spectacle. But it is not, it's not well done. But that's true of anything. If characters are not well done, they're boring. If it's the same damn turning point we've seen, I've been times that boring. And so everything you do have to be well done. inspectable is just one of those things,

Alex Ferrari 32:33

If Jurassic Park would have come out, and it wasn't directed by Steven Spielberg, and written by Michael Creighton, and it would have just been those dinosaurs. With a bad script. Yeah, it would probably have been somewhat successful, because of the spectacle of it. But because of the story, the execution, the people behind it, it turned into the masterpiece that eventually it became so something like Avatar, which is I think, now still the number one, I think it bumped back up after the pandemic. And number one, something like Avatar, now James is coming out with four or five, I think he's, he says he's gonna die on Pandora. This is, this is where he's going. He's not, he's like, I'm gonna be 91 doing part six of this thing. But this is, I'm dying on this hill, he said, but something like something like Avatar is, I think, almost as perfect of a combination of character, event story and spectacle. Because I remember seeing it three times in the theater because of the 3d app aspect of it. And this amazing world that they created the visuals of it. And the story was a very basic simple story that we've seen before. But it was wrapped in this beautiful

Robert McKee 33:48

Done in a whole new way. Right, exactly. The the the inspiration that that the core of Avatar, of course, is that you have a second self. And this doppelganger has Adventures is the app it's not even that it's more than a metaphor. It's a photograph of daydream. Right? Right. It's every kid's life where they dream about having adventures that you know obviously sitting in their in their living room at home, they can't hear and so avatar made that literal and so that his second self is avatar goes off and has adventures. Matrix was similar in that way. And it so that that's a wonderful idea because it tapped into an experience that is so caught you know, every every kid has been experienced. Every kid daydreams about life that they don't have and living in ventures of one kind, or another, whatever. And so the premise of Avatar was inspired. And then the execution was excellent. And then and then there's this. And this is wonderful in an action story, if you can make this work, there's a hidden truth. It's always been there for the whole story that you haven't seen, literally. But the moment the truth comes out, you go off course. And the truth of Avatar wasn't the planet itself was a living thing. Of course, and you go off course.

Alex Ferrari 35:58

Right! It Yeah. And I think

Robert McKee 36:01

That that revelation of a hidden truth makes you the crowds in the audience to go back and reconfigure the whole story they've been watching, and realize it was always there, it was, in some sense, inevitable, that these human beings would just go too far. And when they just, they want to know, that planet had a line. Okay, and they finally went over the line. And it planted a squash and like a bargain, right? And, and it and it expresses something, we really want to believe that there that nature has a greater power. And then we've been pushing nature and prodding the troops boiling nature and poisoning nature, and sooner or later, nature is going to just go squash us if we don't stop what we're doing in time. So it's a master metaphor. I was right? For the the the the destruction of the environment. And it's the environments revenge. And so that's a truth we all want to believe. And so the writing I mean, you know, yes, the directing is wonderful and all the rest but these ideas, tapping into the the fantasy life and bringing that to life and creating a you know, a beautifully told story that has a truth at the heart of it, the nature is going to have the last word. And bringing that into and I'm putting that in the in the film is, is is the reason why people like James Cameron had the great success that they have is because they and they know before they know how to write, you know, action. But it's about something.

Alex Ferrari 38:32

It always is with Jim can't with Jim's work. It's always about time you go back to Terminator. He's saying something. Terminator two, he's saying something in the abyss, which was basically a precursor to a lot of the themes of Avatar. And aliens is it's about a mother. It's about two mothers protecting their young I didn't even realize that Delete. I saw him talking about an interview because I made this entire movie about two mothers protecting their young because it couldn't just be just about aliens and people. I was like, Oh, my God.

Robert McKee 39:06

I was in Westwood. movie after westward, watching aliens. I and I was one of the greatest moments my experience in film. The Act to climax. When Ripley says I'm going back with a kid the audience almost toward the theater down. I mean, they just went nuts. I did too. We all went not with a kid and that's the Mercy see. She's at the mercy of that monster. And what's more than the monster has the big to its clutches from a position of of powerlessness, she's going back to the good old age. So, yeah, we love the genre. And when an action writer gets that, right, creates a world that's really we've never seen before. And tell that story and executes those, those great, those great turning points in ways we've never seen before. It is that you know, as a indicating the title of my book, it is the essence of excitement.

Alex Ferrari 40:41

And still, Ricky wrote one of the greatest sci fi lines of all time, get away from her ubitx Right away. One of the best lines ever written inside, right without Weston. Yeah, it's up there with may the force be with you. I mean, it's just like, it's going away for you. So the better I'm gonna say, I'm gonna say it's a little bit better.

Robert McKee 41:06

Now, it's not spiritual. No, no, no, get away from it. Get Rich, right down to the ground.

Alex Ferrari 41:21

And every one of us and everyone was watching that movie just like, oh, it was just so as we're talking, I'm still getting like goosebumps. I'm getting like, bloods flowing talking about. And that's what a good movie does. When you're explaining the movie to somebody else, and you still get excited about it.

Robert McKee 41:36

You've you've hit the mark. Yeah, that form comes like the form comes to life inside of you. All the spectacles memory, but it's a form. It's the turning point. Going back for the kid get away from me, which is the turning point, the courage of that line, or both of those, whatever. The turning point, gets your heart problem.

Alex Ferrari 42:04

Now in the book, you also talk about the action MacGuffin. Now I am familiar with the MacGuffin. So what is the action MacGuffin? Or if you can explain the MacGuffin to to the audience who might not know what the MacGuffin is. What is an action MacGuffin?

Robert McKee 42:16

Well, there's there's macguffins in a lot of stories, and there's a MacGuffin in crime stories often, but certainly in thrillers, in epics, is defined as the thing that everybody wants. And when you get it gives you power. That's the MacGuffin. It's the it's the thing with an actual physical thing. That gives you power so like in in Aliens, it's the kid right? Get into the MacGuffin monster wants the kid in order to impregnate so to speak. Human beings to reproduce right. And so it's the thing everybody wants when get it and gives them power. So it could be the secret to the to some Nicola

LaunchCode analogy.

Yeah. Any back in in certain films, Alfred Hitchcock that people credited Hitchcock with coining the term MacGuffin. But actually he didn't. He was a writer, friend of his who coined it and he repeated it. Because Hitchcock used it it became famous. It's shocking to realize you don't even have to tell him what it is. So in a film, I'm in North by Northwest, the MacGuffin is secrets. There's some kind of secret, probably a formula some, some probably for a weapon, something like that. Okay. But there's a secret and it's key encapsulated. And people are chasing after the secret throughout the movie. But Hitchcock never tell you what the secret was for what what what was what was in the secret? What what were people going to do what the secret he did deputy vital because he bought he realized it doesn't really matter. It's the thing that everybody wants, when he get it, it gives you power. And everybody's chasing after everybody wants, everybody's struggling to get it. And so from like his point of view, you're thinking, well, if all those characters want that thing so badly, it must really be important.

Alex Ferrari 44:58

So is that the action see because that's something different than the action.

Robert McKee 45:03

It's a it's a motivation.

Alex Ferrari 45:05

It's just a motivation. So you actually motivate action with

Robert McKee 45:08

The pursuit of the MacGuffin and is driving is driving the character they are pursuing the murder my God. If the Euro can get his hands on the MacGuffin, or her hands on the MacGuffin, then they can use that to defeat the villain. If the villain keeps the MacGuffin is going to destroy the world. And so the pursuit of the MacGuffin is, is driving the story. And is often that we've gotten like in that alien the MacGuffin is the victim. Although not necessarily the MacGuffin can be something quite separate from that. And so like all of these elements in story design, coming up creating a really fresh, unique wonderful truthful, fascinating MacGuffin. And, and, and, and generally speaking, generally speaking, it needs to be portable. Because whoever has it has power. And so the hero can get the MacGuffin back. And then the villain takes it back again. And the minute they can exchange this, they can lose it, they've always searching for it dropped into the ocean, and then hero and villain voted, you know, under whatever. And, and so it's got to be a thing. That's important, portable, but in, in, it can be just an idea. But it's got to be an idea that you know, that's written down on a piece of paper or whatever,

Alex Ferrari 47:05

Or someone has it. Someone knows the information.

Robert McKee 47:08

Yeah, something that you can move that helps generate sequences of the action.

Alex Ferrari 47:15

So something like written Raiders of the Lost Ark is obviously the Ark of the Covenant. In Pulp Fiction, it's the suitcase, with the mysterious light that nobody

Robert McKee 47:24

What's in that suitcase in your bed.

Alex Ferrari 47:26

He's still and Quintin won't say,

Robert McKee 47:29

Guaranteed by the day.

Alex Ferrari 47:31

It does not he's not gonna. And every time I ask him, he's like, I don't know. What do you think it is? Like, it's it doesn't matter. Doesn't matter.

Robert McKee 47:39

Everybody wants you gives you power. And you know, they said they actually you don't actually need to know more than that.

Alex Ferrari 47:49

No, that's funny, because that's one of the conspiracy theories about what's in the what's in the suitcase. It's that it's Oh, God being Rames his character, Marcel is his soul. Literally, it's his soul that they're carrying around in there. I was like, oh, that's kind of interesting. His soul. And that the little, the little bandaid on his back of the neck is where the soul got away. These are things that are like, Well, that's pretty interesting.

Robert McKee 48:12

Really.

Alex Ferrari 48:13

Isn't that a fun is enough?

Robert McKee 48:15

It's, it's wonderful. People care that much that they worry about that. It's so hard to get out of the body. Oh, after the Banu. I mean,

Alex Ferrari 48:26

fantastic. I mean, you're talking about film geeks thinking about that movie for decades, trying to figure out what that is. Right now. You also talk about action set pieces. Can you talk a little bit about what a good action set pieces,

Robert McKee 48:41

There are sequences in action. We how many different ways physically can a hero pursue a villain in an effort to rescue the victim? Right? And so there's a limit, you can go towards something right and invade that's a that's a tactic that's an action sequence or you can be quite an escape, you can rescue the victim or or not. Right or lose the whatever. And so, there are there are certain actions moving toward moving away, moving around moving through, in, in a labyrinth across a desert and so forth. There are a certain limited number of ways in the in time and space that hero and villain can interact. And, and so I go through them in the book and given lots of examples of them. And, and I make the point that the writer has to understand its limited time and space, you know has certain limitations, you can go toward you can go away, you can chase someone or BJs. And so, so once you once you, you know, you study the genre as I have, and you see the possibilities of it. And you see the way it's been executed brilliantly by storytellers in the past, that loses the colors on your palate. And so instead of sitting there just wondering, well, why, what could my hero do? And just hitting a wall? Up study isn't the tactics involved? You see, well, I have trust, moving toward moving away, moving through, chasing, being chased, etc. They're rescuing escaping their choice. And so you let those choices play in your imagination. Something like some island. I know, at this point in the story, you know, he would, she would. And it comes come to light. And so and so one of the purposes of writing a book like adding is to the front door, is to present my front door is to open up the possibilities for the reader. Say, here's the genre, here's what has been done for 1000s of years. And there are limits. And so you can go within those limits as you must in budget. That's not a straitjacket, it's just possibilities. And every one of those possible tactics can be done a whole new way to a different environment for a different reason, different characters, and I'm not sure but you have to understand what the elements of the genre that are essential.

Alex Ferrari 52:35

Now, I'd love to break in your book, you break down a bunch of the a bunch of action movies inside of your book is I love to just break down a couple of them even slightly, something like the Dark Knight. So something like the Dark Knight, which is arguably one of the best, super quote unquote superhero films in the genre ever made. Honestly, it's up there without question. And I always use someone like my wife who doesn't like superhero movies, she she puts up with them, because of me. But but when you watch something like the dark night, I was watching them like, Oh, if you just take Batman and the Joker out of this, this is just like heat. It's just a crime. It's a fantastic crime thriller like you take. So a lot of times in superhero movies, you can't do that you take the super out of it, it's over. But Dark Knight is just it really felt like Michael Mann directed it in many ways, because it was so visceral. So can you break down the Dark Knight a little bit?

Robert McKee 53:32

What makes a film like the Dark Knight, so wonderful. And this is true, then the whole action genre is the nature of the villain. The villain is the key to action. If you have no villain, there is nothing for the hero to do. If the villain is an idiot, there's nothing for the hero to do he will trip over himself. Right? Without your help. Right. And so the more brilliantly realize the villainous that forces the hero to rise to the occasion. The hero can only be as fascinating and compelling as the villain makes him makes her and Dark Knight and the Joker The joker is a fantastic villain. And his villainy is so profound, that it the the end he creates a dilemma. Villain creates a dilemma that the hero will have to solve and analyze splendid purpose But it's one of the great crises in inaction stories. And, and, and because this villain, and absolutely ruthless is is a weak word that he is so

Alex Ferrari 55:19

Submissive, submiss maniacal,

Robert McKee 55:22

And sadistic, he likes causing pain in other people. And so he creates this great dilemma at the end, where human beings will have to make a choice to live or die. And, and then that's out beyond the hero's control.

Alex Ferrari 55:45

And it's, it's also, the movie seems to me to be a story about to men's view on the world.

Robert McKee 55:54

Yeah, well, they have, they have points they have.

Alex Ferrari 55:57

I mean, Joker thinks everything should be everything's in chaos. And we're just a step a second away from completely falling into complete anarchy, enjoys that. And he enjoys that. But Batman doesn't believe that believes that. No, people are good, they're gonna make the right choice.

Robert McKee 56:12

So then the Joker creates this dilemma to prove his point.

Alex Ferrari 56:16

Right. And that's the it's a brilliant film. Which also brings me to another problem with there's a specific superhero, who I've yet to see a fascinating film made of, but it's the most famous superhero of all time, because it's the first superhero, Superman. Superman is a character and I went and I want, I'm bringing this up, because I think it's really good illustration. Batman and Superman have always been on both sides. Ones like when Stark was much more. Batman is a much more interesting character, to say the least. By far, but there hasn't been a really great and I've been I'll get a lot of hate mail for this fantastic like Superman film. Maybe obviously the Christopher Reeve film was excellent. I think Christopher Superman too was excellent in the 70s. But in recent years, that when they tried to reduce,

Robert McKee 57:05

Okay, cuz I think Superman one is brilliant, which Mario Puzo Yeah.

Alex Ferrari 57:12

Yeah, no is brilliant,

Robert McKee 57:14

He put he put Superman into dilemmas.

Alex Ferrari 57:19

Now, so why hasn't anyone else be able to do? So why hasn't anybody else been able to do that? Because in Superman one, he was fighting a villain who was superior intellectually, but not physically. And then in Superman two, he fought someone who was superior, quote, unquote, superior, mentally and physically, which was a General Zod, quote unquote, and also much more physical that three of them fighting against one right, right. So there was a there was really stakes there. And then they took his powers away. And and then he had to try to find them back. It was it was such a well done. Those are the two best Superman films, in my opinion. Yeah, besides the Richard Pryor one. The third one, which is interesting to say the least. But what was it about the first one that made that Superman interesting?

Robert McKee 58:09

Well, he had, he had a moral imperative that he owed to his father, who had told him that he must not use his super powers on earth, he must not interfere in human destiny. He's godlike in his powers, as he demonstrates by reversing the spin of the earth and turning back time.

Alex Ferrari 58:41

Fantastic by the way

Robert McKee 58:44

And he mustn't use those powers he must give. It's like you seem like often really, religious people are challenged by the question, Why does God allow evil? And the answer, traditionally has been free will. God wants you to in beings to have free will, to they can choose between good and evil. And, and that's that's the rationale. And so super, Mario Puzo called upon that same idea in Superman one, Superman is God like he has that you know, that, that power, and why would he, you know, allow evil and his father tells him, you have to allow evil, you must not interfere with human destiny. Which means that human beings do what humans beings will do. And we know that half of human beings are evil, that there's an evil side, the human nature. And if you'd like human beings do what human beings do, there'll be a lot of evil in the world. And so Superman estimate that great moral choice to keep his father's sacred commandment, or rescue the woman that he loves. And he chooses love. And, and, and breaks his father's holding command. And so it has, you know, it has the idea in Superman one is rooted profoundly in Christianity.

Alex Ferrari 1:00:44

Oh, god, yes. No.

Robert McKee 1:00:48

And Superman is a metaphor for Jesus Christ. Right, in articles. So these things really connect with people. Because it's about something. It's about moral choice. And that's why, you know, it was, there was a great one. The difference between Superman and Batman isn't Superman. If there's evil, it's really not dark. Okay, it's kind of pastel.

Alex Ferrari 1:01:27

Lex Luthor is not maniacal.

Robert McKee 1:01:29

Nobody's funny, and you know, and he's, you know, he's very fun. Oh, this bill means very fun.

Alex Ferrari 1:01:42

Otisville.

Robert McKee 1:01:45

So, but the Joker is a different thing. Joker is not Lex Luthor, Joker really is evil. And he's sadistic. He enjoys causing people to suck. He lives for because the Joker in Batman is so dark. Batman has the potential man to to create stories that are really compelling and rich. Because Superman operates in a world where evil never gets to that kind of darkness. It's more about the adventure, and the spectacle of it. And so that's why you might feel that the Superman movies are less impactful than the Batman. Because Batman is taking that that whole genre that character is drawing on the a much darker source of ability. It's not as it's not as nicely it's just not nice. Really, suddenly, those that we need are innocent victims. The citizens of Bachmann horrible people excellently give me the it's a question whether or not disabled, who cares? I'm destroying themselves. So it brings up moral question, man, that's the essence of it. That then brings up moral questions that are more profound, darker, deeper than the moral questions in in Superman.

Alex Ferrari 1:03:44

And then something like what Marvel is done with with the cast of characters that have because Marvel's doesn't have dark, dark really doesn't have darkness is as dark as the Joker. It's it's very pastel, like you say, but one of the things and people always ask me, How do you why do you think that? You know, they're so successful over these years? I'm like, yeah, we've talked about some of the reasons. But they've done something that no other film studio has ever done, which is carry characters over a decade. I mean, by the time we get to the Avengers, endgame, and Iron Man, we had been with Iron Man for 10 years and seen him in well in multiple films. And we have such an emotional connection. So you know what happens in that movie is so impactful. Because of that, and that's not done in cinema hasn't been done in cinema. Ever. I don't think I don't think anyone has been able to do that at that scale by any stretch of the imagination.

Robert McKee 1:04:42

You know, there's a secret sauce there that is it's kind of wonderful. I mean, they got you on your kids when you fell in love with those characters, right? Absolutely. Yeah. So that you know that they and they are evolving. They are revealing And in that those are the two elements. How do you create? Series? You know what, what keeps a series alive with air every day now writers are facing that problem in long form television. What will bring people back episode after episode season after season even for years, you know, and the two things, it seems to me that bring people back are revelations number one, you think you know these characters, you think you understand their dimensions and their, their, their, their strengths, their weaknesses, their whatever their natures, you think you understand that with judo. And in, in the future, there will be episodes in which there will be a revelation of who that character really is. That will make perfect sense, but you didn't see prior. So those revelations about the depth and complexities of characters that you that you thought you knew that you now you realize they didn't really know all together that fascinates. And so revelation and change you know, the these, these key characters are at the beginning of the series, and then you watch them undergo over time, change becoming better, morally worse, morally, more will willful, more weak, more whatever they're changing, usually impacts but generally for the better. And so revelation of acts of qualities and characters you didn't see before, and change in the nature of characters that you didn't see coming. Those two things keep the series alive. And and and marvellous has not got that down. And they know how to parse out revelations of character. They know how they have a vision that years and years into the future about where will these characters go. So as long as there's revelations and change, they can do it over and over and over, because it adds to the to the audience's understanding of the characters. And that is a pleasure.

Alex Ferrari 1:07:50

Right, so it's just against those a character like, you know, I don't know how much you know about these characters. But a character like Thor, at the beginning was very different to the Thor that we see now. And he, and he's become one of the most popular were at the beginning, he was one of the least popular exam characters, and

Robert McKee 1:08:07

And now, if you talk to the writers, and they said, We have no idea where Thor would go, Okay, I'm Alfred Della. I and my answer to that is well, consciously then. Alright, but subconsciously, you knew that character had potential? Yep. And you improvised. You experimented, and it turned out that who, you know, there are aspects and that's just coming out of your challenge your creativity and, and, and, you know, what fascinates revelation and change and so you're revealing and changing this character? And, and, you know, the results are wonderful.

Alex Ferrari 1:08:56

And to be fair, I mean, they had 50, or 60 years of writing or 70 years of writing millions 10s of 1000s hundreds of 1000s of stories with these characters, arcing them moving them moving them across time, over decades. I mean, Spider Man is, I mean, how many times have we seen a Spider Man story, but the latest one? Blue, you know, blue, the box office out of the water? Well, because of the nostalgia to there's a little bit of nostalgia, the old Spider Man's coming back, but that was something new. We hadn't seen that before.

Robert McKee 1:09:29

We haven't snow and there's a whole generation of the audience who didn't see it. They weren't born but that was

Alex Ferrari 1:09:37

My daughters were like, is that the original Spider Man and I go, Yeah, can we watch those movies? Okay, let's go back and watch those movies. Yeah, cuz they were like, Who's that spider man? They only know the one Spider Man. And is that another spider mite? Yeah, there's two movies of him. He did three movies. And he's the one that started at all. And it was like really? Like yeah, so they so this is and also when you build something like what Marvel has they've also an ecosystem a world of these characters in these movies. And same thing for Batman and, and those kinds of characters there's a bunch of, and when you run into, like, James Bond more, you know, an older reference of James Bond. When you watch one, Daniel Craig, you're gonna want to watch all the Daniel Craig's. But then you watch piers bras, and you're like, Oh, that's not like Daniel, right? But maybe you like Pierce Bronson. Or you watch Connery here more one of these fun things. So it's fascinating. Rob, Robert, I could talk to you for hours about

Robert McKee 1:10:32

Fun to talk about things you love.

Alex Ferrari 1:10:34

Now, tell me about tell me where are we go? When the book comes out, and where we can get it.

Robert McKee 1:10:38

Book amazon.com, the usual suspects, Barnes and Nobles, whatever. But Amazon certainly in the UK comes out on the sixth today is the second. And so in four days that it are we out. And the pre orders have been spectacular. I hope. I hope that it does what what I wanted to do is to take action as a genre, to yet another level. I want the get really creative, talented people to love the genre, not to look down their nose, not to sneer, but to love it and embrace it and see it as a modern metaphor for life and death struggle to human beings now and in the future. And that, you know, we've been telling action stories since a homer and it's not going to go away. Life and death is a core value of action. And that, that is a struggle that you know that that is eternal, obviously, so, so I comes out on the sixth. And I hope that not only the people who love action, today, but of course, all those people who could consider it, read it. And what they're going to discover is, it's a hell of a lot more complicated and more difficult than you thought.

Alex Ferrari 1:12:27

Yeah, it's not just a bunch of blood explosions and guns, that

Robert McKee 1:12:31

I will make it very clear that this is far more complex, watch more sophisticated and much more difficult than you thought. But if you put your imagination to it, you can do something we've never seen before. So, so I hope I hope all writers will give it a chance read it, see if there's something in that that attracts them. And, and I hope that, you know, in the decades to come that the book will help elevate the action genre to something continuously progressing and growing and capturing our imaginations.

Alex Ferrari 1:13:20

Now, Robert, there's one question I always ask my guests and I don't remember if I asked you this first time and I love to hear your thoughts and please it's very very difficult question I'm not sure you're gonna be able to answer it but I'm going to want to give you a shot at three of your favorite films of all time.

Robert McKee 1:13:38

At the you know, the the the the bear trap in that question is is giving yourself well why and just How pretentious

Alex Ferrari 1:13:55

How many Bergman films are going to be on that list.

Robert McKee 1:14:00

A number of them but not a number one. If, if if it was two o'clock in the morning, and I was traveling to you know, Auckland, New Zealand, full of jetlag unable to sleep. What would I hope with on television? Well, my first hope would probably be Chinatown. And if not Chinatown, then maybe Groundhog Day. So and if not Groundhog Day, the number three please god please give me godfather one, two and three.

Alex Ferrari 1:14:55

All three of them back to back.

Robert McKee 1:14:58

Yeah, that would make a nice i You know, eventually I'd get to sleep. So yeah, those those will be three my first choices wonderful film, and then they are very satisfying and that, you know, the reason I picked those three because I realized over the years, you know that when you are in that situation and you're skipping the channels, looking for something to watch. You kill time. Okay. I have seen the last half of trying to tell the last half of Groundhog Day, and the last last halves of godfathers wanting to so many time, because it didn't the middle the middle option Scott barotz. Turner, and you stop.

Alex Ferrari 1:15:58

Right, exactly. And you know, what's funny on that list, you put Groundhog's Day, which I considered one of the greatest comedies ever written. And it doesn't get the kind of attention and analysis that it should, because people write it off because it was a comedy,

Robert McKee 1:16:15

Snobbery.

Alex Ferrari 1:16:16

It's snobbery exactly but it is so brilliant. So brilliantly written. And I mean, obviously the direction and the candor and the Bill Murray and and then amygdala, I mean, it's masterful. But that was Was there a film prior to Groundhog's Day that used that idea of repeating time, like they're caught in a loop because there's been, again, the cliche is now there are multiple films like that. But I don't remember anything like Groundhog's Day before

Robert McKee 1:16:44

I can either probably was but I can't remember, I know that there are certainly time travel stories. Sure. People go back in time forward in time sideways, I don't know. But living the same day over and over and over again.

Alex Ferrari 1:17:01

Until you change as a human being never seen.

Robert McKee 1:17:04

I think that if we googled, it seems to me there's a little echo in my memory here saying back in the 1930s there was a play and not a film, but a play where somebody was living the same day over and over. And that play was probably considered avant garde.

Alex Ferrari 1:17:33

I'm looking I'm actually looking at it right now. Mirror of a hero in 1987. Wonderful O'Brien, Run Run Lola one. But that's not the same as that Edge of Tomorrow Edge of Tomorrow. But that was way after. Yeah, no, all the other ones have been after I haven't seen anything. The only one that was mirror of a mirror for here on 1987, which was like five or six years earlier. But other than that, not really. And well, obviously nothing is as good as

Robert McKee 1:18:09

It's not about living the same day three times. All right, living the same day, three different ways.

Alex Ferrari 1:18:14

Right. And that's Russia, man.

Robert McKee 1:18:17

And that's Russia. But it's not the same day over and over and that's points of view.

Alex Ferrari 1:18:23

Exactly.

Robert McKee 1:18:24

So the there are there have been stories where where time I mean, when a great was of course a period of gallows play in the 1920s Six Characters in Search about awkward so they these characters come to light that they want. They need actors to act out their lives to free them so that they can go to the next life where the next world whatever it is. So the notion of multiple realities and reliving things. That's that's not new that day. If it isn't original, it's the best anyone's ever done that

Alex Ferrari 1:19:16

It is the diehard of a repeating day movies.

Robert McKee 1:19:21

Yeah, what I love about it is I think another great favorite of mine, for example would be the verdict. Oh, yeah, it's a fantastic The reason I like the verdict. Same reason I like Groundhog Day. It's the redemption plot. The bad guy turns good story. We all hold out in our heart of hearts. Can I become a better human being? Well, I just make the same mistake over and over and over. mistreat my Self and other people the same old way over on, can I redeem myself and in stories like that, like Groundhog Day verdict redeem the character in a beautiful way. And so the the idea of redemption is very powerful.

Alex Ferrari 1:20:26

Robert, like I said, I could talk for you for hours about movies and about story, my friend, thank you so much for coming on the show. And thank you. And thank you so much for all the hard work you've been doing for these these decades trying to educate storytellers and help them with the work that you're doing.

Robert McKee 1:20:42

It's been a pleasure. I seriously I do what I love. And you know, and I've said, I'm writing this story too. I'm going to do a do love in a whole new way again, it's not so I hope. I hope people will check out action. Give it a look. And and let's try to take the genre to two higher, more beautiful level.

Alex Ferrari 1:21:16

Thank you my friend. I appreciate you.

Robert McKee 1:21:17

Thank you, Alex. Take care.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

Please subscribe and leave a rating or review by going to BPS Podcast

Want to advertise on this show? Visit Bulletproofscreenwriting.tv/Sponsors