“Screenwriting is the most prized of all the cinematic arts. Actually, it isn’t, but it should be.”

– Hugh Laurie.

This quote is perfect and a hundred percent true. When it comes to film and television scriptwriting, the writer, known as a screenwriter, has the most important job in the whole filmmaking process.

Maybe, though, you are not familiar with what Script Writing is and why screenwriters are so important.

Have no fear, that’s what we’ll dig into today.

What is Script Writing?

Every film or television show that has ever been produced first started off as a script.

The script is the film (or television show) in written/text form. Scene by scene playing out on paper.

Every action. Every image. Every line of dialogue. Every plot point. If it’s on the screen, it came from the script.

In the most basic set of terms, a script is the blueprint for the film you’re going to bring to life.

In the world we live in today, some people may think that the script isn’t the most important part of the filmmaking process (looking at you major studios). Some will say that if you can hire a talented actor, that actor can elevate a poor script into a good movie.

Or someone might have the thought that if the film can just attract an A-list director, they’ll be able to fix problems with the script.

The only issue is, a poor script will never turn into a good movie, because the script is your film’s foundation, and if that’s not solid, your film will never be strong enough to stand on its own.

With that said, on the other side of the coin, if you have a solid script, your film will only improve when you add talent in front and behind the camera.

We as an audience can overlook bad acting and crappy special effects if we are engaged with the story we’re watching. If we have a connection to what we’re seeing on the screen, we’re more forgiving for those other flaws because the story we’re following makes sense and we’re invested.

There’s no other form of writing quite like screenwriting (aka scriptwriting) because there are certain things you have to be able to do that you don’t necessarily do in another form of writing, like when writing a novel.

In a script, you must SHOW and NOT TELL.

This means, any information that you are going to share with the viewer must be done in one of two ways;

- Visuals

- Dialogue

If you haven’t pick one or the other, your script has been written incorrectly.

A lot of first-time screenwriters get themselves into trouble when it comes to this because they believe that they can write their script just like they would a novel.

That is WRONG.

The great thing about writing a novel is that you can really get into a character’s head. The writer can tell you exactly what that character is thinking/feeling. The character can express themself to the writer in a very personal way.

The write can reveal information to the reader that has nothing to do with the story but gives the story context. The writer can change perspectives and get into the heads of several characters in the story.

If you are writing a script and looking to write the script correctly, you can’t do any of that.

If you need to key the audience in on something you either have to show it as a visual, or a character needs to say it as dialogue.

Unlike a novel, which we the reader hold in our hands and read for ourselves, the script is never seen by the viewer. The viewer only sees and hears what is taking place on the screen.

Also, unlike a novel, everything written in a script has to be written in the present tense, as the action taking place on the screen is happening in real-time whereas a novel can summarize the events that have taken place.

This can make conveying information to the audience exceedingly difficult as a screenwriter and can lead to what we call “heavy exposition”.

You ever watch a film or television show and come to a moment when it feels like a character is just telling you, the viewer, things you need to know because they’re important to the story? That’s exposition. It feels forced if not done properly.

Think of your favorite and least favorite film and television shows. What did you pick as your favorite? What did you pick as a film you hate? If you analyze things closely for a moment you’ll realize, that while you might hate or like a film because of an actor, or who directed it, you’re remembering the film as a whole based on the story it told.

If I were a betting man, I’d say that the difference between your favorite film and a movie you hate, comes down to the story, and that is all on the screenwriter and how he wrote his/her script.

Script writing has many elements to it and can take a while to learn how to do all those things correctly. It can take even longer to become good at it. But it is also one of the most rewarding writing mediums there are.

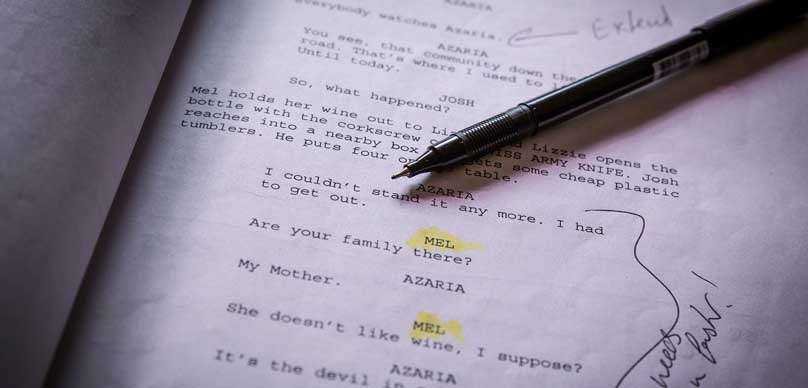

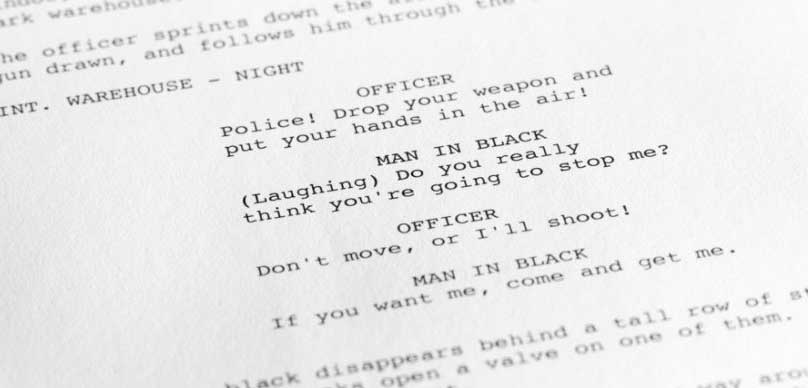

I’d like to close out by writing a little scene to show as an example of what I’ve talked about here today when it comes to writing a screenplay compared to a novel, and how you SHOW in a film and TELL in a novel.

First, we’ll write a very quick scene as if it were inside of a novel.

Novel

Mike paces the room back and forth. He’s covered in his own sweat from having just come from the gym, a place he goes every day for at least two hours.

As he paces the room, a familiar face, Jill, enters the room with him.

Jill’s face, filled with a giant smile. She looks at Mike slightly confused having not expected to see him at this moment. She’s very thankful that she decided to come to the living room by herself.

Just moments earlier, she told her boyfriend, the man she’s cheating on Mike with, to not come out to the living room with her to investigate the noises she was hearing. If he would have come with her, Mike would certainly find out about her cheating ways.

“I didn’t think you’d be here till later tonight”, said Jill. “I was feeling restless and just had to see you right now”, Mike replied.

Jill starts to get butterflies in her stomach. What could Mike need to see her right now about? Does he know she’s cheating on him? She starts to lose her smile as she waits to hear what else Mike has to say….

Now, let’s write this small scene like we would in a screenplay and not a novel. Remember, all the information we need to convey must be in visuals or dialogue to tell our story.

Screenplay

INT. HOUSE – LIVING ROOM – DAY

Mike, paces the room back and forth. He wears his gym gear, holds a large,

almost empty, bottle of water. His face covered in sweat.

He stops pacing as he sees, Jill, joining him in the room.

Jill greets him with a big smile on her face.

JILL

What are you doing here?

Jill looks slightly behind her where the bedroom door is slightly cracked. We see a

shadow on the wall moving around. Appears to be in the shape of a man.

MIKE

I was feeling restless and just had to talk to you right away.

Jill’s eyebrow slightly raises. Her smile starting to fade away.

JILL

(nervous)

About what? Is everything okay?

Mike stops pacing the room. He looks towards Jill. He goes to speak when…

he sees the shadow from inside the bedroom with his own eyes.

MIKE

I knew it!

As you can see, we wrote the same exact scene as in the novel, except we didn’t tell the audience any information. Instead, we used visuals and dialogue to tell all the important information to the audience.

We do not tell the audience that Mike has been at the gym for hours. We show that he’s wearing gym clothes, he’s sweating, and almost out of water. As the audience, we can take this information and figure out what it must mean.

Personally, this is an aspect of screenwriting that I LOVE. Finding the right way to share information with the audience. The more you learn the art of screenwriting the more creative you’ll find yourself presenting the information.

Spoiler

Transcription: So recently, I’ve been writing a lot more often having to get into that sort of narrative feature realm more often than I usually do. A lot of you know that last year I did write my first feature with there comes a knocking. But recently, I’m having to dive into that even more sometimes, even on a deadline. So that’s got me thinking a lot about my process and how I get into that creative realm and what I do to keep myself there and moving forward.

So I wanted to talk a bit about that today, not about the ones and zeros of what actual structure is, or the different types of structure will mention it. But we’re not going to dive into that. So less on how to write and more on how to start writing. And to do that, I asked my friend Ricky stop to help me out on this episode, because he has a similar sensibility to myself. And he just finished writing and directing his first feature starring Idris Elba. So he had a lot of really good ideas that I wanted to bring to you guys as well. So I’m gonna let him start it out.

So guys, my name is Ricky stob, from neighborhood film company. And I’m going to share some tips for you on how we break story when we’re starting out of script. So the first thing that is absolutely terrifying for every single writer out there is facing the blank page. So what we do is we don’t make it blank, the first thing I like to do is actually build a file system, I’ll open the script up, I’ll put the title on, I’ll put my name, I’ll put the date, I just like to be able to see that I’ve started, you know, having little, little goals to make you feel like you’re making progress makes the spirit feel good. So that’s something that we do, we just set up the script. And we like to see that, you know, someday soon, there’ll be 100 pages after that first page, but it just feels good to get started.

I really love that idea about just putting something on the title page, just getting something down on paper to feel like you’ve gotten started, I think that’s such a great way in. And to be clear, at this point, what I’m talking about is breaking a story for a concept that already exists, which is what got me thinking about this episode to begin with.

There’s just this concept that people are interested in. And now I have to break this story. And for me, that means shower time, there’s something about the shower, that is really just such a perfect idea how I think it’s the white noise of the water, the fact that you can’t touch your phone, you can’t look at social media, there are no distractions, it’s just you and your thoughts.

And the main thing that I’m cracking at this stage is who is this about? Who is that person? What are they going through what will change in them and how for me, this is a massive guiding force and figuring out my beginning, middle and end since the character and the theme of the story is going to be what drives that inevitable ending.

Those things are what will lead you to that moment when you say, of course, this is it, it has to be this because it ties perfectly into your story, character and theme. But I’m also just thinking about any and all ideas that revolve around this anything that pops into my head, a line of dialogue, a moment, a set piece, a trailer moment, an image that enforces theme, all of that, and then I will log it in using Evernote and voice recording on my phone, whatever I have available at the time of just chucking it into there, and I’ll collect it into a space later.

A lot of the time, I don’t even really go back and look at that unless I’m stuck. It’s just getting these ideas turning in your head. And the ones that you remember are the ones that stick and end up in the final document. And of course research is a big thing to help me from getting stuck. So if I’m writing something in a courtroom, I’ll go watch a bunch of courtroom videos, I’ll read articles about that. And reading those real life things real situations will really give you a lot of ingredients to start cooking up some other ideas you wouldn’t have had otherwise. But once you have all these ideas down, you know your beginning, middle and end, then what

the next thing we do is we have some very, very practical resources that we rely on to start filling those pages. I think the biggest problem for a lot of writers is that they have these big, beautiful grand ideas, but it’s so hard to take them from your brain and actually put them onto the page. And so there are some really practical resources out there. I’m sure you know, you’ve heard of structure and outline and all these things. But what are the actual resources people are using? Well, I’m going to show you what we actually use.

So there’s a book you’ve probably heard me talk about, I think it’s amazing. I don’t know this author, Blake Snyder, but this book is awesome. And it’s so so simple. And that’s why I love it actually is it takes the really complicated ideas in my mind and helps me funnel them through this prism and say, Okay, how do I take a complex idea and make it simple for film? You know, there’s a great analogy that I think someone told me once I don’t think I made it up but they’re saying what makes films great is not their structure.

You know, just like what makes a T shirt great is not a structure. Every t shirt has a hole for the head, two holes for the arms and a hole to get your body in. But changing that structure putting two holes for two heads that don’t exist does not make the T shirt better. What makes a T shirt great are those little intricacies that are delicate and specific to your voice.

Not the structure of the Actual shirt. And so what I like to do is take the structure of the film off the plate. And what’s really great about the book save the cat is it lays out very simple structures for all kinds of different movies. And if your movie is a, you know, let’s say it’s a fish out of water story, it tells you all the tropes and things that are typically involved in those types of stories. And then you can apply your idea and put it into those into that format.

Now, this might seem to a lot of you, even as I say, and I remember finding the book is like, Oh, it’s gonna make my story so generic. But again, that is not what makes your story unique. What makes your story unique is your vision, your characters, your voice, the people you see in this world, the way that you paint that world, the way that it flows from beginning to end, the way that you uniquely craft them. That’s what makes your story your story.

structure can be a dirty word for people. But the truth is, every film has a beginning, middle and end. And that is a structure no matter what way you cut it. There is some form of structure to every film that you watch, we can get into the structure in another episode and debate all about that.

Like Ricky, I’m also a fan of structure or mile markers, as he called it in our podcast points that you know, you want to hit and knowing these points are a great guide, at least for me, when trying to walk through that beginning desert wasteland of the blank page save the cat does something like a three act structure, I believe and 15 major beats to hit I read it around 2010 and forgot all about it.

The ideas from that book stuck in the back on my mind. And we’re a springboard to my own process. For me, I’m usually thinking more in terms of 6x x one, A and B two, A and B, three, A and B. And this is especially useful for me in the active desert like Ricky, I do split the second act up as well, because I think it makes it pays better and it makes it a less daunting space to travel.

Now this process might change the way that I found my way through in the last few years has evolved overall and changed a bit depending on story too. But at this point, building out the structure. As far as tools go, I’m still in Evernote, although slugline two was just released and full disclosure, I am friends with one of its creators to Auschwitz. But this new version has a way of outlining that I really love.

So I think I’ll be moving off of Evernote and into slugline too for that part of the process going forward, since you can create your acts and beats and easily move things around. It’s pretty badass. So I’ll put a link to that in the notes.

Again, at this point, I’m building out my beats where I think they should fall in the axe. And I’m still not touching the script yet, since I don’t like to actually start writing until I have all my major beats built out where I can see them, rearrange them pitch those ideas to people and watch their reaction and so on. Ricky does something similar here too. But his is more of a physical thing.

Not something like Evernote will throw up tons of ideas literally onto a wall on the note cards. And we’ll ask ourselves, you know, what are what are all the ideas that are in our heads because I like to empty my mind so that the ideas that are in my heads are now physically written down. And for me, it actually creates a mental space where I can fill it with some new concepts because I, I feel like I’m holding on to them if I don’t actually write them down. And so we start by doing that. And then we literally take with save the cat and some other structural devices that we’ve had, we actually work in a four act structure. So that essentially the second act of a three act structure is broken into two acts.

For me, what that helps alleviate is most scripts die in the middle. Because if you think of a three act structure in 120 pages, that means the first 30 are the first act. The second act is 60. And the third act is another 30. But that doesn’t actually make sense to me. So well we also do is, you know, myself and my writing partner, Dan, we always try to keep our scripts under 100 pages if we can.

So if you break out for x, that’s 25 pages practice makes the script move a lot faster. But I’m going to show you something actually. So we write down every single scene in beat of the movie, as we can conceive it. This right here, you can see this, that right there. That is literally every single scene of concrete cowboy. And as we go through writing, we have every single scene written down.

What also creates an enormous level of satisfaction is once you’ve written a scene, you get to highlight the section on the outline. I know this is like super dorky and nerdy, but it feels so good to get to the end and have all your scenes highlighted because that means you’ve written all your scenes.

So now I’m finally writing the script, right? Wrong. Again, this might not work for everyone but my writing is rewriting and I like to do that from the smallest stage up. So my idea dump turns into a rough act map showing the major points, which then drill down further into the major beats. And of course at this point I have the character I know who they are, what they want and what they need.

So now with that built my major beats turn into scenes and I started a rough treatment, a very concise telling of the whole story from beginning to end with the intention of landing all of the ideas and tone of the main piece. So this ends up usually, for me landing somewhere between 13 and 20 pages, but it encompasses the entire story.

What’s great about this is it lets me see if the story is working in a very simple way. And I can show trusted friends to get some feedback on these ideas. Of course, at this stage, you need to be extremely careful who you show, The boat is still on rough waters, and you’re likely not fully confident in it yet, so the right feedback is key. But after that, I take that treatment and start turning it into the script, I copy over what I have placing an under proper scene headings, and I start rewriting and filling things in.

For me, this keeps me from ever feeling overwhelmed at that beginning point from ever feeling discouraged by that blank page. Because I’ve already filled it in before I even started. It’s a psychological trick that I do to myself, but it seems to be working really well. So by the time I start actually writing the film, I’ve already done a ton of work. And the writing gets to be a fun playground of ideas and construction. But it all starts with filling those beats or mile markers.

I think having those little goals, those super small mile markers, pays huge dividends. Because eventually, you know, if you’ve done this every day, for weeks and weeks on end, you’ll see that you’ve taken this big idea that’s been sitting in your head for so long. And you’ve made practical steps of progress to put it on the page. And the biggest part is you’ve got to get out the bad ideas for the beautiful ideas to flourish.

Like, you know, writing is rewriting everyone says that, but that part of the process you have to enjoy is just got to get your ideas on the page. And so really, you know, whether it’s save the cat, whatever app structure you like, figure out the the designs of structure that work for you and your spirit and your writing. And, you know, go forward and write with us.

Although Ricky and I are both talking about features. This does work for short films as well. Although my personal process for short films is a little bit different. There’s less work in the front end involved before I start getting writing. It’s not as detailed before I start into the actual script.

There’s no treatment involved when I’m doing just a short film, but to also say the obvious, we’re absolutely not saying this is how you should definitely do it. We’re just saying that these are the methods that have been working for us if thinking about structure doesn’t help you throw it out. If the idea of six acts sounds ridiculous to you, then ignore it.

What I think is most valuable about getting other people’s process is getting bits of ideas that might work for you and helping Matt to refine your own process or just not feeling alone because you’re hearing other creators like yourself dealing with and navigating the same things you are what matters is the destination, not how you get there that is completely up to you what works best for you find the process that helps you get writing and helps you continue writing and this episode wasn’t about detail on structure or the story ideas.

Like I said before, we may do that in another episode for this, I really just wanted to focus on the process of getting into the process. Because again, it’s what I’ve currently been going through professionally in the last few years, I’ve had to build out this process for myself very quickly. And so far, this is what’s really helped me continue down that path and get the work done.

So hopefully you found it interesting or it’s useful for you. And if you want to know more about process our podcast is back like I’ve been telling you guys last two episodes, we put up a really great and talk a lot about process, especially when it comes to writing. So definitely check the link in the notes for that as well. And of course the contest is over.

We’re gonna start going through everything. And of course announce the winners next week and announce one more contest. So if you weren’t able to get involved with this one, you have another chance. We’ll be announcing that next week as well. So until then, don’t forget to write, shoot, edit, repeat

Julian is a published writer, lecturer, and screenwriting story consultant with extensive experience in scholarly writing.

Julian is a published writer, lecturer, and screenwriting story consultant with extensive experience in scholarly writing.