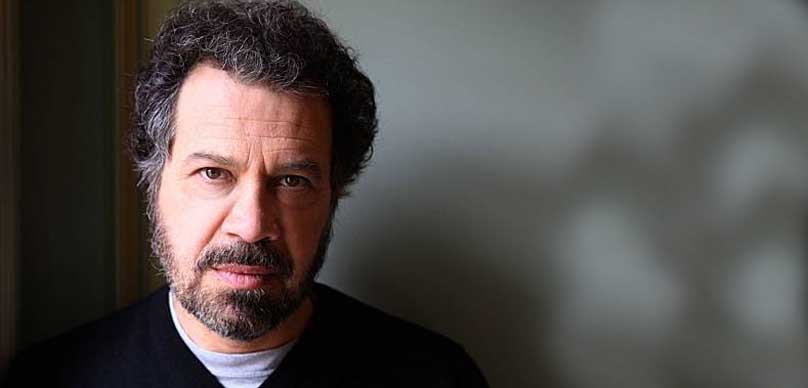

We have been on a major roll lately on the podcast and this episode keep that going in a big way. Our guest on the show today is writer, producer, and director Edward Zwick. Edward made his big shift from his childhood passion of theater to filmmaking after working as a PA for Woody Allenin France on the set of Love and Death. He then moved to California in the summer of 1976 and has since forged a respected name for himself in Hollywood.

Edward Zwick is a multiple Academy Award, Golden Globes, and BAFTA award-winning director, writer, and producer.

Faced with the fear of going to law school during his first five years in the industry if filmmaking didn’t work, Zwick cards turned and launched him into projects that are now some of the most critically and commercially acclaimed in the business. His work spectrums the comedy-drama and epic historical genres. You can see just some of the films he written and directed below.

About Last Night, Edward’s directorial debut was about aman and woman who meet and enter a committed relationship for the first timedespite their personal problems and the interference of their disapproving friends.

He next tackled his first historical drama, and definitely not his last, the Oscar winning Glory.

This is the exceptional story of America’s first unit of African American soldiers during the Civil War and the young, inexperienced Northerner who’s given the job of training and leading them. Based in part on the actual letters of that young officer and brought to life with astonishing skill and believability.

Legends of the Fall: This epic romance follows a man’s fight to come to terms with himself and a family struggling to preserve its simple way of life. Taken from Jim Harrison’s popular Novella, LEGENDS OF THE FALL tells the story of three brothers and the beautiful, compelling young woman who irrevocably changes each of their lives.

Courage Under Fire: A soldier discovers how elusive the truth can be in this first major film about America’s role in the Gulf War. Lt. Col. Nathaniel Serling (Denzel Washington) was the commander of a unit during Operation Desert Storm who mistakenly ordered the destruction of what he believed to be an enemy tank, only to discover that it actually held U.S. soldiers, including a close friend. Since then, Serling has been an emotional wreck, drinking heavily and allowing his marriage to teeter on the brink of collapse.

As a means of redeeming himself, Serling is given a new assignment by his superior, Gen. Hershberg (Michael Moriarty). Capt. Karen Walden (Meg Ryan) was a helicopter pilot who died in battle during the Iraqi conflict, and the White House has proposed that Walden be posthumously awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Serling is asked to investigate Walden’s actions on the field of battle, but he quickly discovers that no two stories about her are quite the same; Ilario (Matt Damon) says Walden acted heroically and sacrificed herself to save the others in her company, while Monfriez (Lou Diamond Phillps) claims she was a coward who was attempting to surrender to enemy troops.

Meanwhile, reporter Tony Gartner (Scott Glenn) is hounding Serling, trying to get the inside story on Walden and on Serling’s own difficulties. Matt Damon lost 40 pounds to prepare for his role in Courage Under Fire, which resulted in a potentially life-threatening illness for the young actor.

The Siege: When a crowded city bus blows up in Brooklyn and a campaign of terror begins to make it’s bloody mark on the streets of New York, it’s up to FBI special agent Anthony “Hub” Hubbard (Denzel Washington) and U.S. Army General William Devereaux (Bruce Willis) to find out who’s responsible and put an end to the destruction. Together, they face explosive danger at every turn when they team up towage an all-out war against a ruthless band of terrorists.

The Last Samurai: Tom Cruise stars in this sweeping epic set in Japan during the 1870s as Captain Nathan Algren, a respected American military officer hired by the Emperor of Japan to train the country’s first army in the art of modern warfare.

As the Emperor attempts to eradicate the ancient Imperial Samurai warriors in preparation for more Westernized and trade-friendly government policies, Algren finds himself unexpectedly impressed and influenced by his encounters with the Japanese warriors, placing him at the center of a struggle between two eras and two worlds, with only his own sense of honor to guide him as The Last Samurai.

Blood Diamond: An ex-mercenary turned smuggler (Leonardo DiCaprio). A Mende fisherman (Djimon Hounsou). Amid the explosive civil war overtaking 1999 Sierra Leone, these men join for two desperate missions: recovering a rare pink diamond of immense value and rescuing the fisherman’s son, conscripted as a child soldier into the brutal rebel forces ripping a swath of torture and bloodshed across the alternately beautiful and ravaged countryside.

Jack Reacher: Never Go Back:Ex-military investigator Jack Reacher (Tom Cruise) leaps off the pages of Lee Child’s bestselling novel and onto the big screen in the explosive thriller the critics are calling “taut, muscular, gruff and cool”*. When an unspeakable crime is committed, all evidence points to the suspect in custody who offers up a single note in defense: “Get Jack Reacher!” The law has its limits, but Reacher does not when his fight for the truth pits him against an unexpected enemy with a skill for violence and a secret to keep.

Edward even won the Academy Award® for producing Shakespeare in Love.

Shakespeare in Love’ showcases a young Will Shakespeare as the up and coming playwright of the time, but he has been disastrously struck by the bane of the writer’s life – writer’s block. His comedy “Romeo and Ethel, the Pirate’s Daughter” isn’t going anywhere and the playhouse is under threat of closure.

What Will needs is a muse, and she appears in the form of the beautiful and betrothed Lady Viola. The path of true love does not run smooth for Will, but the joys and tragedy of his own life find their way onto the page in a moving, witty and spellbinding tale.

The list goes on. Edward has had a remarkable career so far and still has much more to give. Speaking to Edward was like sitting in my persona filmmaking masterclass. We discuss ho he made the jump from a low budget comedy to epic historical dramas, his creative process, navigating Hollywood, directing some of the biggest movie stars in the world and much more.

Prepare to take notes on this one tribe. Enjoy my conversation with Edward Zwick

Right-click here to download the MP3

LINKS

- Edward Zwick – IMDB

SPONSORS

- Bulletproof Script Coverage – Get Your Screenplay Read by Hollywood Professionals

- Audible – Get a Free Screenwriting Audiobook

Alex Ferrari 2:37

We have on the show the legendary Oscar winning filmmaker, Edward Zwick. Now, Edward has directed and written some of the most influential films of the past two decades, starting with about last night. Glory, Courage Under Fire, legends of the fall, the siege, Last Samurai, Blood Diamond, defiance, jack, Reacher and many, many more. He is also the producer of the Oscar winning Best Picture, Shakespeare and love. He's also the creator and executive producers of shows like Nashville 30, something and many more. I mean, the list goes on and on. I was humbled to sit down with Edward and discuss his career, his creative process when he's writing and directing how he directs legendary movie stars like Tom Cruise, Leonardo DiCaprio, Morgan Freeman, and Denzel Washington just to name a few. I was absolutely in awe of, of Edward while we sat down and discussed his his craft and the way he did it, it was awe inspiring to say the least talking to Edward. It was like sitting down in a master class of cinema. So I cannot wait to share this episode with you. So without any further ado, please enjoy my eye opening conversation with Edward Zwick. I like to welcome to the show Edward Zwick, thank you so much how you doing my friend?

Edward Zwick 4:21

I'm doing as well as can be expected given the circumstances of all of our lives.

Alex Ferrari 4:26

Amen. My friend event it is a weird and wacky world that we live in nowadays. And I mean, we've been locked up for a while now. And I'm sure for directors even. It's like your projects on hold, can we can we not shoot?

Edward Zwick 4:44

There's of course, all of that. I mean, I am also a writer. So social distancing. And that kind of sheltering in place is too familiar to those of us that that have to write so I mean, a bit of that.

Alex Ferrari 4:59

Yeah. I'm a writer, and I've been in post for 25 years. So I completely understand. So before we get started, how did you get into the business?

Edward Zwick 5:11

Oh, man, it's, it's a bit of a tale. I began, you know, working in the theater as a kid.I even began directing theater when I was about 15. And on through, I went abroad to France on a fellowship, after college and in the fellowship was to work with experimental theatre companies, Peter Brook, and Irianda Skien. But the truth is, the whole time, I had, you know, had a desperate love affair with movies. But it was a it was a, you know, a passionate fan and a viewer, I didn't really know much about the technology, I'd never really learned exposure. I took stills, but I had, you know, I couldn't read a bolex or work of a viola. And so I, I just didn't, I thought it was somehow, you know, forsworn, because I'd spent all my time in the theater, but through an odd set of circumstances, very odd. I had worked for a magazine when I was in college called the New Republic. And while there, I had had a correspondence with Woody Allen, because he was writing for The New Yorker at the time, those occasional pieces. And we had asked him if he wanted to give us some pieces as well. And he said, Yes. And so he was briefly published in the New Republic that year that I was there. So when I was in Paris, I had heard he was shooting there. I was walking down the street, in Santa Monica prie. And I saw him walking toward me. And I did something that I would never dare do now. Particularly knowing you know, how shy he really was, and is, and I just went up, introduced myself, and I said that he and I had corresponded. And I said, I was around and I was on fellowship money. And would it be okay, if I could just come by the set some time and see what he was up to? He said, sure. But actually, what he said was call me at the George V. And I thought, Oh, well, he's blowing me off, you know, which is fine. And I called him he said, Oh, no, come on by. And I did. It turned out that really, he was very lonely at the time, he was one of the few people when a few Americans there. And I spoke English, but I also spoke French. And within a very short time, he offered me a job to work on the movie as a PA slash assistant, which I did. Right. And, and the he actually was very kind he took me to, to Hungary with them, it was a movie called Love and Death. And, and then, that was really it. Except that he was exceedingly generous. He just suffered my ridiculous questions. And let me just observe, I was despised by the French crew, because there I was talking to the director, which is absolutely forbidden in any kind of hierarchical thing and, and yet, he was quite willing to, you know, indulge me. And and so that I had done something actually in college that Joe Papp had seen, and I had a sort of half assed opportunity to go back and maybe work at the Public Theater when I got back to the United States after this year. But I decided instead that I was going to do it, like so many people before me that I was going to sort of reinvent myself in the movies. And I applied to the American Film Institute, from from France, and it was a very early time there, it was not a it was a very small, not very known circumstance there. And I sent them reviews of plays, I'd done I tend some some things I'd written and I sent them some songs I'd written and for some reason I got in, and I came to Los Angeles in 1976. I think never having been to California, not knowing anybody, I arrived it was you know, about 180 degrees and there the hills were on fire, and nothing

Alex Ferrari 9:31

much has changed.

Edward Zwick 9:32

And I thought that I had made a terrible mistake, having left this this apartment that I'd been subletting in Paris and, and, and and went to the American Film Institute did very, very badly my first year would go home and just cry myself to sleep facedown on the mattress every night. But somehow, by the end of the first year there I had somehow managed to slipped by, and was one of the people asked to come back the second year and make a short film, which I did. And he did no good for me whatsoever. But I,

Alex Ferrari 10:11

you know, was that was that was that Timothy and the angel?

Edward Zwick 10:14

Yes, it was, it was it won a prize at a Chicago Film Festival meant nothing except, you know, some, you know, little plaque that I still have. And but the I had two years of the kind of demystification that you need when you first come here, when you understand what people mean when they say these things to you and and that whole nomenclature of Hollywood and development and you know, those horrible critical phrases that that development executives know, and you have to learn the translation. And probably the most important thing that happened is it Marshall Herskovits. And I met, he was there also as a director. And we became friends. And more than that, I think, after we left film school, because there is no, you know, continuing education, I think we remained each other's friends, but also became each other's teachers in a way. And finally, we began to get some kind of work, and it was horrible. The other would be willing to tell the other person it was horrible. And we would try to analyze why. And that relationship began and continued up, day in both and informal ways. At the same time, I met a guy there named Steve Rosenbloom, who cut my student film who'd never cut anything before. So we figured out that Viola and, and then esteem back and, and, and he has cut everything I've done since as well as having several Oscar nominations. And and I don't know, it was just that sort of that cauldron, that that very serene moment where you actually form certain relationships with people who are actually willing to tell you, you're full of shit. And, and you admit your aspirations to each other. And that's sort of how it began.

Alex Ferrari 12:23

Now, with when you did your, your, either your first short film or even when you apply to, to, or went to LA for the first time, what was the biggest fear you had to overcome? Because a lot of a lot of people listening might have not even taken that first step to walk towards the path of following something that they're passionate about. And they have something blocking them. What was that? Was there a fear? Or did you just go gung ho?

Steve Hodgins 12:47

Well, well, I mean, to be true, really honest, and my father had gone bankrupt when I was in college. And I had applied and had been accepted to law school. So ironically, when you get accepted, I don't know if it's still true now. But in those days, when you got accepted to law school, they and I had gotten this fellowship, they gave me a, what's it called, there was the, the possibility of coming back the year after, or they were able to attenuate my acceptance. And so I had that thing, that piece of paper. And my greatest fear is that I would have to go back and go to law school, because I just, I really had no wish to do it. I applied because I was scared. And I was a middle class kid who thought I had to somehow have something to fall back on. And I guess, you know, that continued for several years, because while I was starving and mooching off my girlfriend, who was willing to, you know, let me stay in her this little rented house. And, and I was, even if for years after that, when I was a script reader and the various things that I did to try to make money, those people who had graduating and clerking for supreme court justices and going to work for white shoe law firms and making a shitload of money and really advancing to the world and I was not as none of you right away. And so there was a, you know, a certain period of time, I would say, the two years of film school and maybe two or three years thereafter, where I was struggling,

Alex Ferrari 14:26

where as you would and and for people listening today, when you were trying to become a filmmaker, it was not the cool thing to do. Nobody really even knew what a film director did.

Steve Hodgins 14:37

Really, sort of true. I mean, I mean, look, I went to I went to an Ivy League school and particularly there I mean, that the couple years before me that I went to Harvard and the guys from the lampoon had come out, and you know, Doug, Kenny, and and and those guys. They had not yet made movies, but they were finding their way here. I seem to remember seeing Animal House like the first year that I actually was there. I don't remember Animal House what year it was. Was it about 77? Is that a good guess? 70?

Alex Ferrari 15:12

Yeah it was rough. Yeah, it was like mid to late 70s. Yeah.

Steve Hodgins 15:15

I think in any case, it was not an acceptable thing. There wasn't a mafia of people all from the same school who had come out here and, and there had never been film courses in the school that I'd gone to. And so it was all very, very new. But when I lived in Paris, all I had done was go to the movies, I probably should have spent a lot more time a lot more time, you know, doing the work I supposed to have done which is working with experimental theater companies, but the cinema tech was their only luck while I was still the head of it. You could spend four francs which was $1. And you can see three movies at a six o'clock and at eight o'clock and 10 o'clock show at the Cinematheque and that would be the Festival of Truffaut or it would be Antonioni, or it would be you know Zoo or Kurosawa and or Indian American films to and Paris, which few people know is probably the best revival city in the world. So they would have a John Ford Film Festival, or they would have a no Preston's Burgess festival. And that's every day, we just go to the movies. So my point is that, that I was there, and I at least had a sense of what I aspired to. I didn't know how to do it. And I did work at ASI, and I listened. And when all the fancy people would come in, tell me about their experiences. I thought I was paying attention. But then when I would try to go and do the work, it never resembled what Sidney polycon been talking about, or, or what Roman Polanski was talking about, as he talked to the students. And I, I just wasn't getting it. And I felt despairing about that. And, frankly, it wasn't for several years of just doing work that was mediocre. And until one day, the penny dropped, and I can't really explain exactly why it happened when it happened. But something was revealed to me about the relationship between what I wanted and what the cameras saw. What I wanted to say and what people said it the actors in their mouths and how stories were told and and and and really it happened like Helen Keller at the pump, I don't know if you've ever seen.

Alex Ferrari 17:37

Of course, of course. Yeah.

Steve Hodgins 17:38

The moment when, when she's got Patty Duke is there and she's pumping in she goes water just oh, Lord. Oh, and suddenly, at that moment, suddenly she can understand language. And for me, that was some language. And, and from then it was a very, very fast trajectory. After very little trajectory, it then began to really gather steam.

Alex Ferrari 18:03

But you struggled for years until that moment happened. And just

Steve Hodgins 18:08

Yeah, I would say the aggregate was was certainly certainly five good years of struggle. And by struggle, I also mean self loathing, of getting an opportunity to write something and then seeing it was bad. And even when I got an opportunity to do a television movie, finally, it was bad. And then the next one was just as bad. I mean, I mean, I'm not sure that they knew at ABC, or even the producers how bad it was, but I knew how bad it was compared to what I was trying to compare myself to.

Alex Ferrari 18:40

Sure.

Steve Hodgins 18:41

And I was embarrassed by it. No, better.

Alex Ferrari 18:45

No, there was. I mean, I've been a fan of yours for a long time and with your filmography, but I saw you on a DVD of this, this this little known amazing acting, directing the actors course called the Nina foch course, because

Steve Hodgins 19:03

Ah,

Alex Ferrari 19:04

can and and I saw you there and and, and of course, George Lucas was in there. There's like a ton of amazing directors who Nina really helped. And I, when I first launched the new film, hustle, I was probably one of the biggest sellers of our course, as I sold tons and because I took it, I'm like, No, I got to promote this to to an audience. And I love that course. But you actually I took the video course you actually took her course. Right?

Steve Hodgins 19:30

Yeah. I mean, there are a few people that mark you I mean, I was lucky enough to have several good teachers in high school and certainly one or two in college but she she just was so radical. I mean, you know, I've I know a little bit about Brando's life and because Anne's life and, and and what who Stella Adler was, and and and what effect she had on people and um and and Sandy Meisner, and and Nina was a student their's, and she took their gospel and apply and then really translated into her own understanding because she too had had a more Hollywood experience. She had been a contract player for Louis Mayer in the in the 40s. And she had then been, she worked with George Stevens and William Wyler as a coach.

Alex Ferrari 20:26

Yeah, then she worked with Kubrick and I think sessile made a million.

Steve Hodgins 20:30

I think something like two mil, she used to tell the middle story. She had the best stories of anybody. But she was also unbelievably tough. Yeah, she was unsparing about what the calling was of directing. And not just directing the actor. But but but storytelling. And, you know, the funny thing, when you have a great teacher, pay attention, you don't always get it right away. What happens is that, at least for me, a year later, or five years later, you'll find yourself in some situation, and then something will happen. And then you'll say, Oh, that's what you meant. And then a whole reservoir of things that will still have been in you will then be available to you, because nothing really leaves if you're paying attention, it's there, it can be called upon. And I think for me, that I just needed to have some thought sort of practical application of doing a thing for it to then be somehow internalized. But once I had done it, and even done it badly, and I maintain good teachers doing it, well, I was able then to reference what she was talking about. And all the things that she talked about, in terms of how one elicits a performance from an actor, how one uses behavior, how one really breaks down a script, it became something that I then took in and applied some of whatever my own experience had been been to try to make it my own. But, but she was she was really formidable. And and, and believed in it as a calling or believed in it as a you know, like a race to it

Alex Ferrari 22:34

almost like a priest.

Steve Hodgins 22:35

I was gonna go there. And I thought at least you said the pretentious part about it. Yes, I think that's true.

Alex Ferrari 22:42

And, and she was I mean, she was a formidable in the, in the DVD and the video course that I saw, I could only imagine being in the room with her. Yeah, it was amazing. I really was. She She was remarkable.

Steve Hodgins 22:54

Now, really, she would really take you apart. She had played the they created something that if I called the narrative workshop, where you would show something that you had shot and we all worked on tape at that time shot at single cameras, if it were film, broke, cut it ourselves. And the exercise was like a Communist Chinese self criticism session, where you have to show the film to your peers, and you're not allowed to speak. And they just tell you what they've seen.

Alex Ferrari 23:24

Oh

Steve Hodgins 23:25

And you have to sit there and fucking take it. And then and then you do some kind of that that repentance thing that you know the Chinese, I am guilty of the sin of pace, I am guilty of this kind of indulgent sort of session.

Alex Ferrari 23:44

That must that must have been amazing. Now, you, you You did a movie in the 80s, which was at least one of those classic 80s movies, which is about last night with Rob Lowe and john Belushi and, and Demi and Elizabeth and it was such a wonderful film. Last night, one of those amazing 80s films and it's a very small, I mean, that's small but it's it's a comedy. And then from from a controlled more controlled comedy you go to glory. Right? How the heck did that convert? Like? Was it an agent? Was it the script? What like what like, how did you get that gig because generally speaking, you don't go from romantic comedy to Epic civil war movie.

Steve Hodgins 24:28

Yeah, it was it was one of those again, flukes. Um, I will say that I had obviously studied American history. So I had a very particular interest in it. I had about last night and had the good fortune of doing well. It's a movie that was made inexpensively made a lot of money for the studio. So they were predisposed to be interesting what I might be interested in. When I said that you can imagine their response was the same as yours. But there's a guy named Jesse Jansky, who had actually been to college with me who had gone to work at that studio. So I had a personal connection with one of the executives there. And two things, they said to me finally, as I, as I first worked with Kevin, john, when they were considering doing it, I was involved with a producer named Freddy fields, who's a very sort of legendary character for any number of reasons in Hollywood, as a producer, and then having created what is now ICM, but um, we found out that there was going to be a reenactment of the 100 and 25th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg taking place on the field with the reenactors. And there were going to be 1000s of men, maybe three or 4000 men on the field that day, July 4 125, years after 1863, that would have been 63. A, it was like 89, something like that. And we convinced them to give us $25,000 or $20,000, whatever it was, where I could go with a friend of mine who's a cameraman, and another cameraman we picked up in New York, and Freddie and me to go on to that field, and just shoot what it might look like. And I didn't know what I was gonna see when I got there. But I read about these reenactors. And we went there. And we had to put on the union uniforms because he wouldn't let anybody on the field who wasn't actually in the reenactment. But there we were running around, is 100 degrees in Gettysburg in this mid summer. And we we shot hot, several 1000 feet of film. And I brought it back to LA and Steve Rosenbloom, who was not yet an editor. He was actually an assistant. But my my close friend, we took the film, and at night in the cutting room, when he was done with his day job, we snuck in there and we cut the film together and put it to music and put together about couldn't have been more than a five or six minute reel. But it was magic, because it was the dust would come up and the horses would go through and these cannons would go off. And, and and there was no narrative,

Alex Ferrari 27:23

right? But it was a sizzle. It was a sizzle.

Steve Hodgins 27:26

I invented the sizzle, apparently,

Alex Ferrari 27:29

apparently, because I was like this is the most amazing sizzle I've ever heard of.

Steve Hodgins 27:32

Exactly. And so we did that. And showed it to the studio. And the one thing the studios are sub are subject to and this is I think explains the sizzle. Which is Oh, well we're incapable of imagining it. But if you show me something that is in fact there, maybe maybe that makes it makes sense. I mean, I I find this sizzle to be a little bit offensive when someone's taking my film and 10 other directors films and saying that they've done it. But that's how it's gonna be because God helped them if they could do it the same way. But, but that was one thing that happened and they looked at it, they went, Wow, that's pretty great. They said to me, we will make this movie for a certain budget, if you can get Matthew Broderick to agree to do it. Now, Matthew Broderick at that point had done Ferris Bueller. He's not exactly the most logical, you know, choice to play in this kind of movie.

Alex Ferrari 28:35

Right.

Steve Hodgins 28:37

But that began in a bit of a conversation with Matthew and and some real hesitation he had about doing it and having to win him over to that idea. But the good news was they said basically, if you could get Matthew Broderick to do it, then all the rest of those guys, you know, those black guys, you know, well, you know, you'll you'll take care of that.

Alex Ferrari 28:59

Yes, it does a couple guys, whatever, whatever doesn't matter, which which, you know, amazing, amazing.

Steve Hodgins 29:04

It's an amazing story. Because I mean, I had known Denzel, because the year before we had started 30 something and, and, and Denzel was, I think he was they're still doing Sandy elsewhere at the time right away.

Alex Ferrari 29:17

That's right. He did say nice.

Steve Hodgins 29:19

And I'd seen Morgan do something that bam. And Andre Brower was still a senior it was still in. Still in his final year at Julliard. He had never done anything before. But it it bespoke something that's, I think, also interesting to talk about which that their approach to it was essentially as a white savior narrative, No, man, and that's what they wanted the movie to be. And therefore there was a lot of a lot of pressure put on me to really lift up that character of Shaw and talk about his how he was trained and where he was born. And it got there and there was literally, but two reels of film and, and really to put the burden of the narrative on him. And I had to write a lot of it. And in fact, as we started, I had to shoot a bunch of it. But it became abundantly clear that when I started rehearsing with the guys in the tent with Denzel and Andre and Morgan, Jimmy, that there's that was, that was the story that we shot that first scene and looked at it in dailies. Or let me back up for a second when I looked at the stuff with Matthew alone. And it looked like a kind of bad movie for television, because it was arch, and it was stilted. And it was just something you'd seen before. But when I started realizing what these guys had, it just all revealed itself to me. And I began to write more for them and figure out ways that there would be other scenes in which they would have figured even more prominently in the plot. And so that when I finally showed the movie to the studio, I cut the first two reels, I literally began with Matthew Broderick, on that field in that letter, and he meets Morgan Freeman, you know, three minutes into the movie, when he's lying there on the field, and starts meeting the other guys, you know, six minutes later. And the movie became what it became, which is not to diminish anything that Matthew did, or or to diminish his import, and, and, and, and his performance. But these guys were in a state of grace. They were they were representing something that I could only imagine or humble myself in front of.

Alex Ferrari 31:54

Yeah, and, and, and from what I when I saw the film, I mean, all I all I can remember from from the back of my head is Denzel just, it's just Denzel, I mean, Morgan and everybody else. And Matthew was great, but it's just Denzel. You just saw, he became Denzel and glory, like he became

Steve Hodgins 32:14

Yeah, in a relationship with us where we made several more movies together. But, but one thing we will say also, and this is how I tried to make that transition. And I think this is really important to say.

I know that about last night was you know, people in rooms talking and 30 something we should come right after at the regional Mirage the same time was the same thing. But I shot so much film, meaning in that movie, and in those 40 episodes that had preceded this I'm like a lot of the directors that became really great directors, who shot to Reelers, you know, George Stevens who had shot you know, a Mac senate and and john Ford, who had shot you know, crummy westerns and all that shooting film, cutting film, doing it, figuring out what makes a scene work was, again about gaining a kind of Felicity and, and, and the kind of chops as a jazz. You know, trumpeter might fingers scales as a pianist might. And one more thing, which is I went back to some of the Masters that I had so loved. And I think I watched Ron and Kaga Boucher, and the Seven Samurai 100 times. Because what Kurosawa did with those movies, he did not have a lot of money, and we didn't have a lot of money for glory. He showed me how to fill that frame and how to stage that in depth and how to give the impression of scale. And I, you know, stole mercilessly from his technique, even though it was different, you know, period and whatever. And I would have, I could afford, you know, four days in the movie where we had six or 700 extras or five days, right. And I figured out how to space those shots, when I needed them through the different aspects of the story. So that then when I only had 200, or even 100, and Phil inserted those shots into the bigger shots in your mind as the audience you're there among the 700 or 2000 of them, because you have to remember there was no CGI,

Alex Ferrari 34:47

none at all in

Steve Hodgins 34:48

All camera. It's all in camera. We couldn't we couldn't duplicate and tile and do any of those things.

Alex Ferrari 34:56

That's amazing. Now moving forward in your in your career. I've noticed that you worked a lot on the upcoming. Yeah, you've worked with a lot of up and coming. actors, like from Denzel. You know, Brad Pitt, Matt Damon encouraged to fire, you have a heck of an eye?

Steve Hodgins 35:17

Well, I mean, I thank you. And and I do, I am proud of that. And by the way, I would include, um, Claire Danes, and Evan Rachel Wood in the Intellivision, too, I think it's, it's, it's freeing, frankly, is that would go back to the theater and, and having some confidence in my estimation of who an actor really is, and who he is for that part, as opposed to what his reputation might be, or what other movies you might have seen. of, I would like to think that I would cast unknown actors as movie stars, and I would try to cast movie stars as actors that trying to find some equalizing of the voice and, and ask the same thing of both of them.

Alex Ferrari 36:08

Now, how do you know how do you sculpt those remarkable performances? Because throughout your filmography, I mean, you have amazing actors, obviously, but but use your films for specifically this, the performances are so sculpted, how do you work with them? How do you kind of come up with these from Leonardo and Blood Diamond to to Tom and Last Samurai? And these kind of films, like their performances are? So there's depth to it? How do you sculpt a great performance? Um,

Steve Hodgins 36:42

I think it begins with a kind of trust, that has to be earned. And I think that comes out of some set of conversations that begin, and they begin very early. Sometimes it's doing the research together. Sometimes it's doing physical things, you know, Denzel and I, I mean, the guys, even all of them in the tent, as they were learning how to, you know, load a musket and do drills with with the, with the reenactors, or Tom working with the sword or, or drinking Jagermeister, with Leonardo with guys who had been in the South African Defence Forces. There's a building of vocabulary and, and trust that that's part of it. I think there's also a commitment to honesty, about not bullshitting an actor or a movie star, about what what they're doing and not being the person whose job it is to suck their cock, but rather to really demand something of them, right, because you've done the work and, and, and the truth is, they want to do the work. And, and I think, obviously, over time, when you've done a certain number of performances, actors might come there, knowing that you might have some notion of what you're doing. Right and, and how to get them there. But by the way, you evoke Nina. And, and, and, and there's a very, very good example of something that I might things I might have heard her talk about, when I was 22. That then, when I found myself at 35, in these relationships with movie stars, or 45, those, that's when a lot of that stuff came in handy. Because, you know, she had worked with mighty Clift, and she had, you know, understood that, that that, that actors and actresses were a very particular breed. And there are very specific kinds of issues that you could understand that they have to deal with. And, and you could be sensitive to those. And then one other thing, I think, and that is maybe it's going to sound a little bit woowoo. But I think the directing, kind of directing, and I believe there's a certain amount of exchange that happens, a kind of my experience of the material first say as a writer, or even breaking it down just as a director of someone else's work, but that as I approach it, I want to understand the nature of the experience that the actor is going through. And when I go and talk to that actor, somewhere in me, I'm also communicating to him or her. What I believe the nature of that experience to be, and it might be the tone of my voice. It might be a touch on the shoulder. It might be my posture, it might just be the intensity and the sweat. I don't know what it is. But I think that there is some willingness to go deep. And to understand where that actor wants to get to.

And to create an ambience where that actor can be comfortable to discover something. And to feel like they have the time to discover it, a lot of what you do as a director is to is anti entropic push away all the entropy of life of noise and traffic and pressure and your watch in the end, is to give them at least the illusion that they have a safe space,

Alex Ferrari 40:46

Right

Steve Hodgins 40:47

which they can create. And, and something that I that I talked a lot to Steven Soderbergh about when we work together is creating a circumstance in which the default is truth. And just to say, the script and what you're asking the actor to do, is to not make some ridiculous transition into lines is not to have to give along expository speech for no reason. To have a costume that feels right, to have a set that feels like it's real, to not ask them to not to stage things in a way as to be arbitrary for the camera, but to have let life in to that process. And as a director, however much I prep, there's no substitute for me sitting there and letting them play an experiment and discovering myself even things I might not have known, because there is life happening in front of me. And if you can create enough of that, that the actor feels as if, as if they're cheating. As as if there's just life happening. And by the way, when you read about it, and you read about what the gift was suddenly of Kazakhstan and Brando, or, or James Dean or, or, or, you know, different actors, that was the Revolution, the revolution was was bringing life onto the stage and in front of the screen that was not very different than the life we know it to be. It's just that life put into extreme circumstances.

Alex Ferrari 42:34

And I think I think the two words that really sum up the performances I've seen in your films is depth and truth. Is there is that there is just, there's substance, it's not it's not it's not a veil, very thin performance, with all of them. Because some actors, you know, movie stars, in some movies, they're Oscar caliber. Other Other times, you just like what happened. And it happens with that happens with every artist in every field. But but but there's a consistency in your work. And that's why I wanted to ask you that question.

Steve Hodgins 43:09

Well, I mean, I think it's also it's also who you're surrounding them with, yeah, what are the nature of the words, you're asking them to say, you know, I listen, I I have found at times that the hero of a production has had been the, the, the costume designer, yeah. Or the prop man. Or, you know, the skinny knife that Brad has, and legends of the fall that was the built and that somehow becomes this, this thing and I and obviously, the the DP who creates this universe, everybody, if you're if you have those magnificent people, they are also creating this edifice on which the performance then can rest, but the edifice is already higher up and the performance is already lifted in some way. So it's, it's, it's, it's about everybody else, too. And of course, not me. I sometimes think that it's the hair and makeup, people who are in the trailer, who are the first people to see that see the actor in the beginning of the day. And the last people to see them at the end of the day, that are as instrumental in giving them that sort of confidence to to go out there like on a, you know, those umbilical lines that the guys go out on a spacewalk, you know, out there, they're out there in zero G, and you're back behind the camera with a cup of coffee, but but they're out there and they have to feel like they're like they're being taken care of and supported.

Alex Ferrari 44:39

Now, another another theme I've seen in your films is just the massive scale of many of your films. It's just so many like very, you know, just very epic films from legends of the fall to The Last Samurai to glory. As a director, how do you work with such a massive Live, not only crew, but just the 1000s hundreds, if not 1000s of people that might be in front of the lens sometimes. How can you like because I look, I have a, you know, when I'm directing, I'm directing a scene, I'm directing a scene with four or five people in a room. And you just try to keep hold of two or three cameras, and making sure everyone's you know, just trying to take the narrative. How can you even grasp that man?

Steve Hodgins 45:23

I know this, this is gonna sound a little bit fatuous. But I think it's it's just as hard to direct a scene with five people in a room as it is with 500. I think, you know, when you have 500, it's, it's about your canvas. What what is on your palate? And and in some odd way, there's more to photograph when there is 500 people out there, right? There's there you can juxtapose what's that that meyerhold phrase, neither, you can never be too close nor too far away. I mean, you have the you have the long shot, you have the great scale thing, which then juxtaposes to a close up you have, you have a kind of palette that is exciting. Action, certainly, particularly action where there is stakes that are emotional, where you're not looking at action for its own sake, but you're actually following the story. And that action has a purpose with that story that you're telling me that individual actor or that set of actors. And part of it is the thing that I never thought I would be well suited for it always having a certain amount of patience. I mean, you know, there, there have been there have been days when you arrive, it's 530 in the morning. And then about five hours later, six hours later, the ad says, okay, that's lunch, and you haven't got a shot. When, and, and, and, and Okay, and you know, you're getting written now it's three in the afternoon, and you're convinced that you're going to get fired, and you're going to have to lose student days, you have to get some confidence that you're going to then accomplish when you do those things, the things that you want that you've got the number of cameras, and then you've got the right shots, and you've done a shot list. I mean, II don't do shot lists of people in rooms and talking and whatever. But on those things, you damn well better have your shot list because you're not coming back there, you know, with 500 extras the next day?

Alex Ferrari 47:23

Yeah, so like, it's kind of like that old, that old story of john Ford on a script. The Indians take the fort. Like it's literally one line, but it took two weeks to shoot. And I'm assuming once you move that machine to reset that machine, that's another day, almost sometimes,

Steve Hodgins 47:41

there's so many great stories about that I won't bore you with and there's there's a great one about David lean, and they're setting the the the, the attack on aka but you know, without the camera without filming the cameras and, and, and there's, um, what was I gonna say there was another thing that reminded me of, of I, you know, yeah, you just have to that that's a real, that's about a kind of redundancy. I read a now something really weird has happened to the visual on the front, okay. I am I there's a book that I read by Rick Atkinson called the army at dawn. He's a Washington Post reporter about and it's about the Allied it was part of a trilogy about World War Two. And it's about the invasion of North Africa, which was an utter failure. And it's about all the preparations they had to do to create amphibious landings. Well, they'd never done them before, what is an obvious landing, they had invent the amphibious craft, and they had to understand about supplies and all of this. And it was about the redundancy of checking and rechecking and having these endless meetings with all of the departments and making sure that everybody's on the same page and, and being honest about you can and can't accomplish. And what they discovered when they did the landing, is they got it all wrong. But they never could have done D day if they hadn't fucked up so badly in North Africa. And so part of it is also making really stupid mistakes, as long as you then don't make them twice,

Alex Ferrari 49:27

then that's pretty much filmmaking. Not one one part of filmmaking that is not really taught in schools very often. And I know I felt I've had to deal with it I'm sure you have to every director has ever had to deal with it. Is the inevitable politics of being on set the hierarchy dealing with politics of actors or crew or studio or producers. Can you talk a little bit about how you as a director deal with those, those those panels Tick moments, which, when you have a group of people, it's going to happen.

Steve Hodgins 50:03

Yeal. well, you've you've mentioned, you know, by those seven people you've mentioned, if you if you triangulate them, you've mentioned about 49 different relationships, so, so maybe more, so I can only I'd have to talk about them somewhat separately. Um, the one thing I would say is I have over time, come up with a kind of an analog to what a film set is. And, and, and, and because it's not a startup, and it's not a team. It's not a business. It's this, a group of people all coming together with a common goal. But the goal is ephemeral. The goal is a story. And I think of it a little bit like the sort of like the sailing ships in the 16th century. Everybody on that ship is a master, the ship's carpenter, the sail maker, the cook, the navigator, everybody is really is an expert in what they do. Um, and at the front of the ship up in the in the in the prow of the ship is some guy with a big long beard, blown back by this spray in the wind. And he said, I don't really know the way, right, he has idea. But somebody's got to say that. And all the rest of them are probably capable of being that guy who's up there, but they don't want that gig. They're perfectly happy being in their own depart, doing their thing as experts, and also grumbling that the son of a bitch up there doesn't know what he's doing. But, but they're wonderful people, they might film people on a set are funny as shit, they are capable of working in long hours in inclement conditions with crummy food. And, and, and, and, and there's a love there. And there's a commitment to this thing. And it's, it's romantic, it's a beautiful thing. So generally, I find a crew to be just the best part of it are all that now, when you fold in the actors who have their own little world and their own set of issues, they have to be that they have to be dealt with in a very particular way. So as to be able to keep that separateness to a certain degree and be able to have the focus and the concentration that they need. But you'll also find that if actors are not in gratitude for their opportunity, or not aware of what's happening, they could lose a crew to an actor could get a crew to do anything for them. Or they could have a crew that's working against them. And it's all it's often a factor of what their nature is, you know, a little bit have a little bit of sensitivity on their part or kindness or awareness of what other people are going through goes a very long way. And and vice versa. Because a crew could sabotage an actor just in some very subtle but very unhappy ways.

Alex Ferrari 53:19

And when No, and I think the same goes for directors like it if you don't, I mean, I've had crews, I see I've been on sets where the crews are completely against the director, either in either in television, because television is even rough. And that's a whole other conversation. Yep. But in a feature world, they come in and if you just a little bit of kindness, saying hi to them, saying thank you, you know, all those little things, making sure that they that they're fed on time that these little little things go such a long way when you get when you're at our 12 and you need them to go another 30 or 40 minutes. Totally,

Steve Hodgins 54:01

totally and, and also I listen, I started I was very young, when I started really directing. I mean, I was maybe 26 wives, and I would do some of these shows at Universal. And those guys, you know, they had been working for 35 years, they've done 1000s of hours, right? And even when I started making movies, it became very clear to me that the dolly grip I was making my third movie so I shot six hours of film and he shot 600 and when I would start to say Okay, now we're gonna put the camera over and by the time I point he was already moving the dolly over to where the camera was going to be because he knew so so the part of it was actually surrounding myself with people who really knew much more than I did and trying to pay attention and really ask you know, dumb questions and and and try to listen

Alex Ferrari 54:57

their absolute absolute absolute

Steve Hodgins 55:00

When you when you try to then factor into the executives, and oh, yes, that's that's a whole other story about you know, yeah,

Alex Ferrari 55:08

that's another podcast, that's another podcast. Now, um, have you ever had to deal with an unprepared or difficult actor? And if you have what do you as a director? If it's a star, if it's a bit player, if it's if it's a secondary supporting character? How do you deal with that as an actor, as a director to keep the engine going?

Steve Hodgins 55:34

You know, I've dealt with actors who were too anxious to do well. And that's something you deal with. But when you deal with an actor who's not prepared, was drinking at lunch? At the bad scene, and I'm not sure I handled it very well, I'm not sure I even knew what to do. Because there's not much you can do. I suppose if you're in the position to fire someone, you can. But you also know that when you fire someone, you're also hurting yourself. Because the they're not going to necessarily say, Oh, it's fine. We'll go back and reshoot all this, and we'll give you all the time back, it'll inevitably hurt you in some way. I think there are two things. One, there are a lot of us, I think, who are perfectly willing to call each other out of the blue. And I won't mention names of guys who called me. But I could tell you that I have presumed to pick up the phone and call another director and say, before I work with this guy, I've heard something just talk to me, tell me honestly, this will never go any further. What am I looking at? What am I up against? Because that's the kind of honor among thieves. Yeah, if they've had a bad experience, they don't want they don't want you to have a bad experience. Directors, ironically, are very, are very supportive of each other, we may be competitive in some, in some industries mind as to who could do a better film, but any director who's been through it more than once, or has a life in it has real compassion for for their peers. So I will call people and they will call me and so that's one failsafe to avoid that thing happening. And only once I've been forced to use an actor that I didn't want to use that I heard stuff about. And it almost ruined, I think it actually did really hurt the third act of one of my movies, and I will not mention who that is, but it was, it was bad. And I hated it. And I should have fought it harder. It was because the movie was going out way over budget and that needed, they felt they needed another star and it was just a bad scene. So that was that. Um, but the other thing is, try to if there's a way that you know, you're not gonna get a movie star to read for you. Right? But you can, but you can try to spend time with them. And, and even though it seems awkward, really try to talk honestly and get the measure of who that person is. Because people will tell you who they are. I mean, there's, if you really listen, when you anybody in life, when you beat them, they want you to know who they are. And, and and if you can get past your own anxiety or your or your expectations, you know, I need this person to be in my movie, therefore, I'm going to like him. Right? In fact, what they're saying is crap, or what they're saying is terrifying about, you know, their, their entitlement or their, you know, pomposity, or, you know, they're ingratitude things that really make you crazy. You end up if you end up casting that person, then you get what you deserve.

Alex Ferrari 59:04

We'll be right back after a word from our sponsor. And now back to the show. Amen. Amen. Very, very, very true. Now, in Last Samurai, which by the way last summer is one of those movies that if it's on, it's a it's a remote throwing kind of throw away the remote kind of movie for me. Like if it's on wherever it is, in the movie, I just stopped Okay, I'm in I'm in and I'm, it's one of those films for me. I absolutely adore it. I also am fascinated with Samurai culture and cemetery history and I haven't recorded our autograph. In in, in the it's, it's on the wall in the back. I'm, I've got my samurai sword in the other room. I mean, I'm in so that's why when I saw that trailer for the first time, I was amazed. Some there's so many things in that movie that we could talk about, but The fight sequences in that film are so wonderful and so amazing. And I know Tom, from what I hear from other directors I've talked to who've worked with him, and also just the legend. He is a serious, committed, professional actor, and he wants to do everything himself.

Steve Hodgins 1:00:20

Yeah, I mean, yeah, there. Um, I would say, there is only one shot in that movie that Tom did not do. And that's when the horse that he's riding in the final charge takes a fall. Right? Right. Because, first of all, the insurance company would never let us do that. And I would never let him do it. Because the guys who did it were the gypsies from Spain, from zingaro, the great horse circus, who were the greatest writers in the world, and who had trained with those horses for four months before then. But he wanted to, but he wanted to do it. Oh, I'm sure and by the way, he's riding in the charge. He's, I'll tell you what he's in. He's in the charge on the on foot when the two armies come together and hit each other. Oh, he's in that shot that. But But what I remember is, is it was February, we didn't start shooting the movie. We till like September, October. So in February already, I remember he was renting a house someplace on the west side, and like, there was a tennis court there. And I went to go see him one night, and it was foggy, cold. And it was nine at night. And I remember walking down to the tennis court, and he is out there with a sword guy working out. And that's seven months before we shot the movie. And, you know, some of the learning Japanese. And I mean, you know, there was a great guy, a guy named Nick Powell very talented stunt guy who was really good with sword. But I also found that a lot of the Japanese had their own you know, experts and they had shot a lot of Samurai movies. And and there were there were some guys on that on that field of there were 700 Japanese who came to live in New Zealand with us, when we made that movie even created a village with our own doctors and diet and whatever. But there were guys on on that field who had been in those carousel movies. So and and there are certain guys in those battles, who must probably who die about 100 times, I think that it's

Alex Ferrari 1:02:46

as good as good stunt people. Do you just put another wig on them? Get them out there again.

Steve Hodgins 1:02:51

But But I do remember that literally. It was a kind of ghoulish exercise, certainly in that final battle about saying, okay, okay. What's another way to kill someone? How many ways are there that I could devise to kill someone? tell you another interesting thing. You probably like we there's the scene when that when the samurai first come out of the mist and they charge and they're on horseback and horseback week week, we built an app that's an animatronic horse. It was a million dollars to build a horse. That is probably only in about 28 seconds of film.

Alex Ferrari 1:03:36

How is that? That doesn't make a lot of sense ROI wise. Like there's not a really good return on investment or is there? I

Steve Hodgins 1:03:42

mean, seriously? No, it does. Because in the middle of this remarkable season, you have your movie star, doing things that you would never let a movie star do. Okay, horse rearing, turning sword bending, twisting to an end then getting t boned by another horse and going over.

Alex Ferrari 1:04:04

I guess you're right. I guess you're right. You're absolutely right.

Steve Hodgins 1:04:06

There's no other way to do it. And you save yourself. Okay, this whole sequence is going to be five minutes. If you got 30 seconds of that movie star doing that in the middle of it. It's probably worth it in a movie that cost $130 million. That million dollars was well spent. Yeah, but true.

Alex Ferrari 1:04:26

That's amazing. So like so that sequence that fight sequence in the in the back alley, the when the samurai surround Tom and that the way you shot that in the way that the timing and the slow mo and the way he the way he was thinking like the images. How do you approach a scene like that?

Steve Hodgins 1:04:44

Yeah, I am. I I read a I read a book by john McPhee talking about Arthur Ashe, and I think it might have been osuna playing a tennis match in the 60s. And it's a brilliant analysis of, of sport, but also competition and I remember him time trying to break down a tennis stroke into the composite motions of every change the weight and and and a vision and timing and and what the human brain might be capable of doing and understanding all at once. When you see a player in hang time twisting and reverse the ball and then going opposite Elio, since you know, things that are or I once had a cat, that I slow motion and dropping the cat from higher up upside down and seeing the cat come and find his feet with a kind of gyro ability that he would have. So the idea was to say, how would it be possible for someone because you know, in Samurai movies, when you see it, they're doing it, but it's very fast. And you're taking it on faith? That that's how it would have been. But I said to myself, okay, is there a way that we could literally break it down and see it, and do it in the reverse? Usually, what you do in action, or at least what I seen before, with action is some action starts in it immediately goes into slow motion

Alex Ferrari 1:06:33

Right?

Steve Hodgins 1:06:34

And that's how it happens. And I said to myself, well, what happens if we do it, and then find a way to then go backwards, and almost like that, that, you know, he's been training? Right. That's, that's why this makes so much sense. And when you're, when you're training it, you know, you train and you train and you train, and they try to say to you, and the whole theory of that was, which is what coaches used to say to me, if you did well, oh, man, you were playing out of your mind? Yeah, you're playing out of your mind. What does that mean? The zones are opening, you're only reacting,

Alex Ferrari 1:07:14

Right?

Steve Hodgins 1:07:15

So this first show him playing out of his mind, almost been unaware of what he had done. And then go back and almost to recapitulate it, in that penultimate moment, that leads up to the last moment, that was the whole theory. But Tom, I will say, Does every, and those guys are swinging, they're not they're not sharpened swords. But if one of those swords would have hit him in the face, or in the arm, that would have been, you know, the, if not the end of a career would be the end of a couple weeks of shooting. So, so imagine the amount of time that he spent rehearsing that with those guys to do that. It done all I wanted to show it all in one take first.

Alex Ferrari 1:08:05

Yeah, and that and the reason why all of that works so beautifully is because it works into his character. And that's what I love about that action sequence. It is it is a statement about what the character is gone through. It is not just an action sequence to look cool, which is fine. And there's those those stories in those films. But in this your action sequence are actually telling is a storytelling aspect. It's not just look how cool you swing a sword. It I mean, I believe I'm not interested in action for its own sake.

Steve Hodgins 1:08:36

I mean, I like it sometimes. So this is not who I am. I, if there's a reason. If something is accomplished narratively in it, then there's a reason for it to be in the movie. And sometimes that's a by design. It's great if you can reveal anything through behavior, rather than through exposition. And in this case, it It literally begins with that first scene with the character playing YuGiOh hero hero Yuki sanada when Cruz refuses to, to, to lie down, and get up, he's trading that stick Oh, so good. But it's a progression. And even that scene, by the way, which we did in the rain, which made it much more dangerous hurry for him. It happens to be a master. But that to have slipped if one of them slips at that moment in that wet, sloppy mud. That's just, you know, right out. So

Alex Ferrari 1:09:43

it is it is again and if anyone listening has not watched last time. Please do yourself a favor and watch it because the actual sequence is the story. I mean, I cry at the I mean, you're just tearing at the end of that. It's just so emotional and so well done. You go to something like Blood Diamond, which is again, another dis. I mean, it's not a war movie, per se, but it is a war movie. You know, there is definitely elements in that. And that's one thing I wanted to ask you. There is something I've noticed in your filmography as well, is there's a theme, a lot of the stories you tackle are deal with war, and even even pawn sacrifice about Bobby Fischer is a internal and external war of one character. So what draws you to that kind of material? Because it started way, way early with glory.

Steve Hodgins 1:10:37

I don't know.

Alex Ferrari 1:10:42

Because, I mean, you do see you sort of pattern, right?

Steve Hodgins 1:10:45

Yeah. I mean, look, I'm not the first dramatist to realize that, that in those extreme circumstances, you can find great story. And you got to go back to you know, let's start with Homer. Right, right. Right. And then and then the aliens are pretty good one.

Alex Ferrari 1:11:03

Time, it's okay. It wouldn't, it wouldn't have a good box office opening,

Steve Hodgins 1:11:06

I'm just gonna write and Shakespeare did, okay. With, with several different wars. And, you know, I mean, I, you know, in those moments, obviously, things are simplified. Yeah, the nuance of care, I had done plenty of ambiguity and ambivalence when I was doing 30 something and doing little, you know, modern, you know, behavioral comedy. But with this, there's an opportunity to juxtapose that kind of emotionality that's at the same, it's not strange to see that at the same pitch. Because that's the world that it's in the outside the external reality matches the internal reality there. So it doesn't seem stupid. For that to be at a certain depth of intensity.

Alex Ferrari 1:12:00

Now, the siege which is, by the way, one of my wife's and mine favorite films, which is he she adores that film. Um, she's the one thing I want to ask you there, it's an eerie Omen to 911 like you did that in before 911. How, how did you come up with that story? Because, I mean, imagine when you, you know, when you experience 911, you're like, oh, Mike, Oh, my God. I mean, it's Yeah,

Steve Hodgins 1:12:24

obviously, that certainly was a but

Alex Ferrari 1:12:28

comparing it to your to your story to your film, you're like, Oh, my God, this is? Wow. Well,

Steve Hodgins 1:12:32

I would say two things. One is that I was reading a lot about Europe, and what Europe was going through with terrorism. And, and I have a number of friends who went into government, and whom I could talk to write out what they anticipated. Because a lot of times, what seems like it's happening someplace else, is inevitably going to happen here. And I you know, and, and, and, and that only gets faster and faster. We look no further leaving in the pandemic, you know, which Oh, that's gonna be just over there. No. It is. It is one world in that regard. And, and so, I guess I was paying attention. I wasn't prognosticating. I was trying to pay attention to what was happening in the world. And, and I just felt that that was coming here. And by the way, the guy two people helped me on that script very closely. The first was Larry, right. Larry, right, who then wrote the looming tower. He's one of the greatest journalists of our day. And he wrote this book about the pandemic. A year ago, before this all happened. He's a, an amazing journalist who's paying great attention. And the others men omis, who's a friend and a great writer, he was actually I think he wrote a couple of the Indiana Jones movies and and he's a politically very savvy guy. So it was, you know, I had help. And I also had helped by talking to people from the, the the FBI, CIA, counterintelligence, Task Force, Task Force and and talking to people who were, you know, experts in the field of hostage negotiations, and at every stage, you know, if you're, I mean, I did have some experience at the very beginning of my life as a journalist, and I still hold on to the understanding that there's no substitute for talking to people and know what they're talking about. Especially if you bring a movie star with you.

Alex Ferrari 1:14:54

That always helps is what you're saying.

Steve Hodgins 1:14:56

Yeah, it really does. You mean then i would i would be there with the CIA with Annette Bening and and and and then would they would have stonewalled me at the minute she walked in it was like, Oh, wait, let me show you this secret document from like,

Alex Ferrari 1:15:12

what do you want to know who shot JFK? Like? Exactly.

Never underestimate the power of the star power of movie stars and trying to get anything done in this town in general. Now, you you have been, you've been a writer from for most of your career actually, I think it was in most of your career you've always been writing and you write most of you work that you direct. And then also you write scripts that are are, are that are not something that you direct. What is your writing process? Like? How do you get into it? Because arguably, directing 500 horses, taking a hill is probably easier than looking at a blank page. Yeah, I

Steve Hodgins 1:15:57

think that's a fair way to put it. I mean, I know that when I'm writing, I'd sure rather be out on the set with 500 horses, but I conversely, when I'm out there with 500 horses, I sure wish it would like to be back someplace else writing.

Alex Ferrari 1:16:11

It's, it's Yeah, it's always that yeah. So but what is so what is your process? Do you start with character? Do you start with plot? Is it Do you like what is that process for you?

Steve Hodgins 1:16:22

Hmm. I mean, I mean, I I do believe I mean, I mean, sometimes there are simple things I know when I when I started writing Blood Diamond. I Chuck Leavitt had written a very interesting script that really didn't have much to do with what we were doing but it was set in the time of you know, that the conflict diamond you know, moment and but I kept thinking and thinking about the story would be in as reading a lot of books and reading a lot of articles and talking to people whatever. And I came up with a phrase and the phrase was the child is the diamond. And like that, I put that on my like on a post it note and if you think about it, um, you know, the the the Solomon Vandy character is looking for his son. Leo is looking for the stone, Jenny Connelly is looking for a bus story. And somehow, the idea that the each had these goals were started it all spinning in my mind as to as to how one could, it's sort of a john Houston sort of plot really, where these different people have these different agendas, and they come together and, and apart. That's conceptual. And part of it is conceptual, I think, certainly, for samurai, no, Marshall and I, and john Logan, we've had because john Logan and I did the first drafts together. The idea that a man would end up turning against everything that he has been trained to do and believe in and fighting to the death for it.

Alex Ferrari 1:18:20

Right

Steve Hodgins 1:18:21

is a concept. Yes. How does that man get from that place to that place? And then we talked a lot about Samurai culture. We talked a lot about Zen. Um, so that's part of it. But the other part, I know is going to sound it's kind of sounds kind of hokey. But what's a movie that I really want to see that nobody else is making?

Alex Ferrari 1:18:46

Okay

Steve Hodgins 1:18:47

Can I entertain myself? Can I can I give myself the experience of doing this kind of doing this movie? Because while you write a movie, you are living it. And in fact, maybe the best performance of it is the one that nobody sees. It's the one that only you have been able to imagine and see in your mind. Because it's inevitably going to be reduced by compromise of money and time and performances,

Alex Ferrari 1:19:14

right.

Steve Hodgins 1:19:15

Is there any way that I can, you know, just sort of re imagine my experience of being a kid in the movies or that person at the Cinematheque at 22 years old? Just just been, you know, hypnotized by, by a thing that that really interests me.

Alex Ferrari 1:19:38

Fair enough. And that leads me to the next question. What drives you as a storyteller?

Steve Hodgins 1:19:48

Oh, look, you early in this conversation, you use the word calling?

Alex Ferrari 1:19:58

Yes.

Steve Hodgins 1:19:59

So I'll throw it At the end, I'll say, I'll say, I think that there is purpose. And I think there is value. In trying to hold a mirror up to our society, I think the storyteller had a role in the primordial cave cave, trying to explain to everybody why that saber toothed Tiger came and took that child away that day, or what that Eclipse meant, you know, that we've, we've, we've had a role. And it may be just to make people laugh, and it may be to to deal with their fears. Or it may be even to explain their own ambivalences or to give them language for something that they don't have. But but there's there is something of a ministry in it. And I and I do think that the reason that certain movies are memorable and others are forgettable is that the movies that are memorable, somehow dig into those personal secrets and, and internal workings of the mind and of the heart that that people want to explore. And they want to start with it. And when we are in movies, we are weeping for ourselves, we are weeping for those characters, but we're weeping for the parts of ourselves that identify with those people in that moment that have something of them or have experienced something, or will experience it. I had a conversation with James Newton Howard yesterday, who is a some wonderful composer with him. I've done several films. And he said, You know, people say they, they, they they, they make movies. Because they want to explore something they've experienced. He said, I write music, to experience something that I've never felt.

Alex Ferrari 1:22:06

Right.

Steve Hodgins 1:22:07

And that was so beautiful to me. It's very honest. And he and I want to have an experience. And and and then I want to offer it to other people. And that's a whole other way of sort of turning it around.

Alex Ferrari 1:22:21

Fair enough. Now I'm gonna I'm gonna ask you a few questions. I ask all of my guests. If you could go back and tell your younger self one thing, what would that be?

Steve Hodgins 1:22:34

Be? be bolder,

Alex Ferrari 1:22:37

take more chances. Take more chances. You'll be okay. It's okay. Yeah, don't be so scared. Yeah. I'll agree. I'll agree with you that I feel like my 20s were a complete waste. Yeah. Now, what advice would you give a filmmaker trying to break into the business today?

Steve Hodgins 1:22:59

Well, I mean, it's kind of remarkable in that, you know, with it with a consumer HD camera and, and avid for Mac and, you know, some you could make anybody can make movies now. I mean, I saw you actually had Shaun Baker on your show once before. Yeah. And, and and his first movie, and even a second. I mean, you you know, he, I think that it's not nearly so much about technology as it is actually coming to understand why you have any notion of telling a story. You know, what is it? The i i've never, yes, there's a whole world of people that, that make movies, because that's cool. And that's a comic book. And, sure, God bless them. And it's fine. It just, it just, it just does not, you know, my jam. But, but you've got to have something to say. You've got to, I would say, for a filmmaker, it's not just to look at other films, but to try to look at life and to read books about psychology and politics and science. And I think it's curiosity for the world about how people behave and how the world behaves. I just don't think it's about trying to figure out where to put the camera. Or, or or you'll you'll be, that was, by the way in going all the way back what I watched with Woody Allen, when I first was 21 years old. He didn't know any of that stuff. They were people I realized he was a writer who has somebody wanted to say and some of it was funny, and so it was emotional, but he had people who could help him learn that and he learned it and I loved it too. But I'd like to think that there were things that I was interested in beyond the process of making the film. I love the making of the film. And we've talked about that today even. And it's, it's delicious. But it's actually what's gonna give a film some kind of substance is something in it something worth saying.

Alex Ferrari 1:25:27

Now what is the lesson that took you the longest to learn whether in the film industry or in life?

Steve Hodgins 1:25:36

Boy. Yeah, I guess I would say that, when I was really young, and beginning, certainly in the, in the industry, that I thought that I was making movies, so as to get something else was to get fame or money or sex or, and some, some validation that I didn't get in childhood. And, and so so so my process was fraud, my process was contorted to some degree. And, eventually, and it took a while, I realized that, Oh, actually, it was the doing of it. That was the gift. I made movies, because I really liked doing it. I did it, for the joy of it. And, and, and the reward. It's not the credits on IMDB. It's not anything because they're all going to be forgotten. Like, everything is forgotten. It's it's, it's the the reward is the those relationships and the memories of, of the struggle, and, and the defeats and the triumphs, but to have the experiences that is that is the thing that that I have.

Alex Ferrari 1:27:08