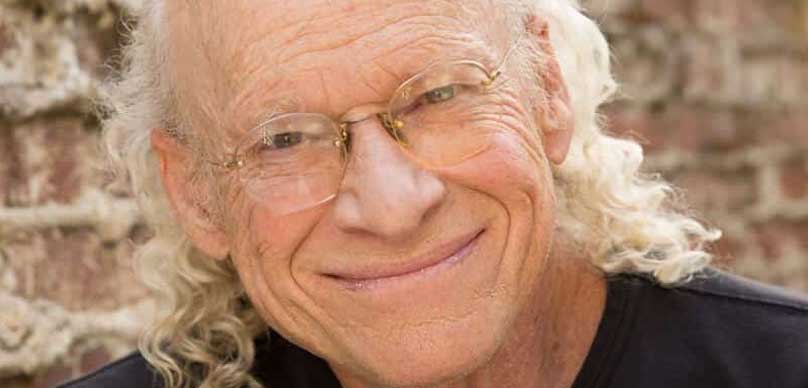

Our guest today, is expert storytelling educator, author, and UCLA professor, Richard Walter— bestselling author of Essentials of Screenwriting: The Art, Craft, and Business of Film and Television Writing. He recently retired as Professor and Interim Dean of the UCLA School of Theater, Film, and Television where, for more than forty years, he chaired the graduate program in screenwriting.

The amazing thing about Richard is he has been the instructor of some of the most amazing screenwriters in Hollywood history. A handful of them has been on the show, including Sacha Gervasi, Jim Uhls, the writer of Fight Club, and Paul Castro, just to name a few.

He’s written scripts for major studios, television networks, and even wrote the earliest drafts of George Lucas’s American Graffiti. Talking to Richard in this conversation was essentially sitting front row at a masterclass of storytelling and screenwriting.

It was an absolute treat talking to Richard. Not only has his work been appreciated in the US but in other parts of the world, conducting lectures in London, Paris, Jerusalem, Madrid, Rio de Janeiro, Mexico City, Beijing, Shanghai, Sydney, and Hong Kong.

He complains that L.A. has relentless good weather which he says, ‘Is not writing weather’, yet, in 1988, he released his first instructional book Screenwriting: The Art, Craft, and Business of Film and Television Writing (Plume). This was followed a decade later (2000) by his debut novel Escape from Film School, which tells the sprightly tale of a young man who makes it in Hollywood without ever leaving film school.

Richard is one of the few OG writers who have studied, and taught through the evolutive eras of screenplays and screenwriting in Hollywood. With his wealth of knowledge, he released his third and most recent book, Essentials of Screenwriting: The Art, Craft, and Business of Film and Television Writing. In this one, he shares the secrets of writing and selling successful screenplays for aspiring screenwriters.

It contains highly coveted lessons and principles from Screenwriting with material from his companion text, The Whole Picture, and includes new advice on how to turn a raw idea into a great movie or TV script and sell it.

Besides his outstanding career, we chatted about his love for Spike Lee films, we talked about screenplay structuring and many more. It’s been an absolute treat talking with Richard.

Enjoy this epic conversation with Richard Walter.

Right-click here to download the MP3

LINKS

- Richard Walter – Official Website

- Richard Walter – IMDB

- Book: Screenwriting: The Art, Craft, and Business of Film and Television Writing – Amazon

SPONSORS

- Bulletproof Script Coverage – Get Your Screenplay Read by Hollywood Professionals

- Audible – Get a Free Screenwriting Audiobook

Alex Ferrari 0:43

I'd like to welcome to the show Richard Walter, how you doing Richard?

Richard Walter 3:31

I'm doing well. And thank you I'm happy to be here.

Alex Ferrari 3:34

Thank you so much for being on the show. I mean, we've been trying to get this going for about a year now.

Richard Walter 3:39

My fault

Alex Ferrari 3:42

but I've always wanted to have you on the show because a lot of my former guests have been your students like Jim boules was your student I think Paul Castro as well and a bunch of I mean to me I mean the list goes on and on of your ex students

Richard Walter 3:58

That was my teaching assistant. And I also brought him in to teach from time to time after he had graduated.

Alex Ferrari 4:07

Yeah, exactly.

Richard Walter 4:08

I am I am blessed in crossing paths with with artists like that. I consider myself very, very fortunate.

Alex Ferrari 4:17

Yeah, exactly. So I've always heard about you through my other guests and then when I did research on you like I gotta get Richard on the show and we just one thing led to another my schedule your schedule technology, but we're here now and we are

Richard Walter 4:28

we're gonna get the students might you know, my dad rest. His soul was a musician and quite a successful musician, the bass player primarily in the classical repertoire, but also jazz and pop, and it was primarily a performing player. But he also was the bass department at Juilliard. The outstanding a world class music conservatory needs to say that if he was working with musicians have limited talent That'd be okay. You're still reaching, you know, you're still working with people who are trying to be creative, who are reaching and stretching and taking risks, you know, with their lives. And that would be an expansive even though they're not going to, you know, become successful professional musicians. Being part of supporting creativity in that way is an affirming expansive experience for the treating the structure. But more better. He is to say, if you're going to teach artists, you might as well teach the best scientists in the world. And that's what we have at Julliard, he would, he would tell me and that's what we had at UCLA when I was there. And I'm sure Still, we still do. And it is a blessing to, to work with writers of such skill, as the two names you just mentioned, have been guests on your own show full Castro and GMOs boy, by the way, made a film that was produced by another student was Lewis. He, you know what, but we we butt heads with these students. They compete with us, they challenge us and they keep us fresh. They keep us from getting into the kinds of ruts and grooves that you can get into in a freelance community, like the screenwriting community in Hollywood. So I am the lucky guy in that in that equation.

Alex Ferrari 6:16

Yeah. And you? I mean, you use the chair and obviously teach at UCLA is famed screenwriting program. When I when I've heard I was hearing about it, I think even from Coppola went to UCLA. So I mean, even back then, I mean, you see, there's obviously there's USC and UCLA and NYU but UCLA screenwriting, it was unpair. Yes.

Richard Walter 6:37

Yes. I am, myself a Trojan to I went to film school. at USC. In the 60s. George Lucas was my my classmate. We call that the Lucas era, but I'm told George calls it the Walter era. Just joking, just like to say we were the first class to move on from the academic community to own Hollywood except for George, who owns Marin County.

Alex Ferrari 7:07

Pretty much and I've been there I've been to Marion County, he

Richard Walter 7:10

it's funny his the ranch is on Lucas Valley Road, but that was Lucas Valley Road 100 years earlier. You can't make this stuff.

Alex Ferrari 7:19

There. Yeah. When they were looking for it when they're looking for property from what I saw. They were like, did like which ones should we pick? And George like? Well, I think we should pick the one on Lucas value.

Richard Walter 7:31

In any event, yes, there are, I think three major film schools and it's UCLA USC and NYU. People that a if I will argue with me, I think asi is a great institution. Some people say Columbia, you know. But yes. In screenwriting, UCLA was number one, not according to me itself suffering of me to say that, sure. But you know, the New York Times the LA Times The Times of London, and those are just the times is also the Wall Street Journal. They they identified the UCLA pro writing program as as outstanding. And I like to tell the writers there that we the faculty, whenever we would meet them in the fall, the new class and have orientation, I would always tell them that, you know, that the faculty sitting on one side of that, this table, and then the room was filled with the new students. And I would say we sitting here and we faculty at this, on this Saturday, but we are the second most important people in the room. The most important people in the room are the writers, we can't be better than our writers we intend on Oh, we rely on them. Not just predominantly, or largely, or to some extent, completely and totally 100% to make and sustain our reputation. So the first challenge in a screenwriting program is getting the writer if you you know, we can we can supply all sorts of things, but you got to bring your own talent.

Alex Ferrari 9:01

And that's one thing that I always I always tell people is like talent is is great. But it's not enough. It's never enough. Because there's a lot I've known a lot I'm sure you've met a lot of talented writers out there. I've known a lot of talented people, but talent without hustle talent without work ethic. It's useless.

Richard Walter 9:20

Just like I said about the student speed. Faculty being the second most important people in the room talent is the second most important quality that you have to have if you're going to if you're going to succeed as a writer refreshing you got to have this discipline. And what is discipline? I'm not sure what discipline is but here's the measure of discipline I'm you know, my 13th on a Casio this guy they they jumped in. They stole this guy's half million dollar watching from a restaurant in the Beverly Hills. I don't think anybody's my Amazon delivered by Amazon for 13 bucks. Yeah, but the point is, it's how much time will you give to this How much time would you get to this script? How much time will you give to this career? People don't quit. You know, people don't fail in Hollywood, they sort of just just drift away. It's a question of staying in the game, I recommend everybody that you'd be as lucky as you can. And that seems you're laughing and it is kind of a joke, but it's only a kind of a joke, because the truth is, you can affect your luck. And how can you do that by staying at the table? You know, if you're around the table at poker, everybody gets the same cards over the night. Come on. It's how you play those cards, how attentive you are, how disciplined you are, to your strategies and wielding them and stuff like that. So it's really about putting in the time and I will tell you, I see more writers defeat themselves by hiring, you know, john wooden, very, maybe probably the most famous name associated with UCLA. used to say, be quick, but don't hurry.

Alex Ferrari 11:00

Yeah, that's a great quote. Oh, my be quick, but don't hurry. It's apt. It's absolutely true. And I mean, I've been, you know, I got to LA around 12 years ago, and I already had, you know, some experience and

Richard Walter 11:11

where did you come from

Alex Ferrari 11:12

Miami, Miami, so it was a smaller market. But I'd already made my bones I had been directing and, and doing post production, everything. So when I showed up, I showed up with a wealth of experience already. But the first year here, I learned more than the past five there, because of the caliber of people I was working with here. And I've been here now over 12 years. And it is it is something that you do like being here, you just get opportunities that you just wouldn't get elsewhere. Not in before and we can I don't want to get too deep into the weeds on this. But before you had to be here all the time. Like there was no other options. Really, if you weren't New York, you could be in New York, maybe but not really la was the place to be. Yeah, but But now, LA is you don't have to be here, you could maybe go Atlanta, you maybe could go to other areas of the of the US and also of the world. But LA is always going to be LA in one way, shape, or form. But you don't have to do it as much as it used to.

Richard Walter 12:11

You know, Los Angeles is the world's most creative community and all platforms and all formats and all media. I came to California, I'm a New Yorker, I'm a Queen's boy. I was living in upstate New York. And I was going to continue, I've gotten my master's, the summer of 66. And I had about six weeks to kill before going back to get my PhD. back east, and I'd never been west of Cleveland. So a little along with a buddy of mine, I got into my VW Beetle. And in three days we got to the coast. And I was planning to be here about three weeks but I I fell into film school at USC and I never, I never really looked back three years later, that was August of 69. Three years later, my wife and I, and all this I'm sorry, that was 66. Three years later, August of 69. My wife and I went on holiday we just motored we wanted to go up to the Redwood National Park. We were still relatively new to California and really dazzled by this dazzling state. And we went on Indeed, we went as far as the quad dunes that the Oregon California border. The first night we got to San Francisco and stayed overnight with a friend and from my friend's house I call this was a Saturday night. I called water merge who was a classmate of mine at the UFC and a huge, famous and winning sound man and the editor amateur. He's a famous editor with a very famous book on editing blink of an eye. He's also this is a little less known to the film people but he's also an amateur astrophysicist. And amateur in that context is not a pejorative, it means he's he's not formally trained, but he's known all around the world for theories that he has regarding orbits of, you know, planets around suns, for example. And I mean, this guy is just a giant. He lived at that time on I say, a houseboat with his wife just off the the shoreline at Sausalito in the Bay Area. Just the other side of the Golden Gate Bridge. And the previous time that we'd been up to San Francisco we had a lot of friends there and we used to go up there a lot we'd had a big party on Walters boat. So I called him up that night. I said anything any action going on? He said nothing tonight on the boat but tomorrow's a few of us are getting together for brunch at a place called the Trident and eatery along the water in Sausalito. So we we invited us and we we joined them there so there was nine people my wife and I the other seven included an Oscar is a woman who would would win an Oscar for editing. Her name was Marcia Griffin along with a writer, he was not there but Richard Chu. And she won the Oscar for editing Star Wars. Scorsese's Alice Doesn't Live Here, I believe it was. She was also her husband is also there, George Lucas.

Alex Ferrari 15:23

Right. It was Yeah, she also helps with Star Wars.

Richard Walter 15:25

Right sitting next to him. Caleb Deschanel, very famous cinematographer, but probably better known now for his very successful daughters who are actors. With with Caleb is the guy whose name is a little less known, less well known, but a wonderful fellow in a very successful producer David Lester. He produced most of Ron Shelton's movies, Bull doormen and so on. did a lot of line work wonderful guy. So there's Marcia Griffin, George Lucas, Kevin a Chanel. And David listed also Walter merchant, his wife, Aggie, also, john malleus. He's known as three years.

Alex Ferrari 16:11

what's what's it what's what's witness, Mr. Spielberg? Steve wasn't there. Steve Spielberg was

Richard Walter 16:16

six months later, I get a call from Jerry Lewis. I believe it or not, when I went to sc Jerry Lewis came on to teach a directing course. And I ended up being his teaching assistant. He called me six months after that meeting at the trade end, in Sausalito. The phone rings and it's Jerry Lewis, I still can't believe that ringing phone and it's Jerry Lewis calling me. And he said to me, he was he shooting a movie at Warner Brothers. And in December in January, this was actually about like, the October November was a few months after the Sausalito dinner and a few a couple of months before he shot the movie. And it was looking for dialogue director, somebody to work with the actors, run them through the lines and this and that he works with certain actors who are amateurs and he needs and he wondered if I could refer him to somebody if I knew anybody might be good for that. So of course, I said to mobile, what I mean, and and he said to me, of course, that's that's what I hoped you would, you would say. So suddenly, there I am, you know, heartland really brand new, not yet full out, even out of film school completely. And I'm the dialogue director on a major animators on a movie, you're talking about the things that happen to you when you're in LA. And when you actually mix with mixed with people I used to tell people, it's actually an advantage to be from out of town. And I even know writers who would mask their addresses. I know one writer who had who made it appear as if he was in living in Tennessee. He thought it was sexier and niftier to be somebody other than yet another writer from the San Fernando Valley, you know. And the truth is, unless you were actually working in TV, on a staff situation, you did not need to be, you did not need to be in town. Again, if you're in television, either on staff or even a freelancer in those days, you need to be available to pitch. And you could I knew a guy in love. Eric tarloff, who lived up in Berkeley and would come down you know, I mean, I used to, I lived in Queens, and I used to take the, what we call the BMT, the subway into Manhattan to go to high school, Stuyvesant High School in Manhattan. And nobody ever gave me a glass of tomato juice on the train, you know, like, on the plane. So it really didn't matter where where you are. And to no small extent today it doesn't either, except that the big thing in television now is really in the business is staffing Did you get staffed on a show, and stamps do meet regularly daily around the table and so on. So you do need to be in town? Yes, there are some productions like that going on in Atlanta and other Vancouver things. However, it's still pretty much centered here,

Alex Ferrari 19:12

right? And I always tell people that, you know, when you're starting out, if you can afford to get out here, it's probably best because you got to do some time out here. make those connections, make those relationships, establish yourself. And then then if you want to leave, but almost everybody as far as screenwriters and filmmakers, almost all of them except for maybe some of the famous New York guys like Spike Lee and, and Marty and I think even Oliver Stone was out here as well. But some of the day they are everyone spends time out here building those relationships, taking those meetings until they established themselves, but is definitely something that young riders should take a look at.

Richard Walter 19:50

Yeah, I mean, I expected to be here for three weeks and here it is. I'm gonna give it the salary so I'm gonna give it another 54 years and it's still hasn't worked out for me back then. The truth is, I grew up in New York, everybody hated New York, it was a very much, much criticized place. And New Yorkers never defend New York, you know, to live there, that's your problem.

Alex Ferrari 20:18

I was reading. I was raised in New York.

Richard Walter 20:20

Yeah. Somebody, you know, tells a story to a Londoner that maybe they're there. Something happened to them that was was untoward. And I say, Oh, so sorry about that. That's most unusual, you know. Sorry. Yeah. But if you if, if it were in New York, and they say, yeah, that's not you know, what they've done on my monitor, they threw her on the train and nobody's trying to convince you. Nobody's trying to recruit you to move there. I stayed in LA because it's the greatest place on the planet. I'm right now. I'm looking at the snow capped mountains across the valley. Culturally, artistically, creatively, there's not a more more fertile ground for that anywhere on the on the on the planet. It's a hugely diverse communities are shifting I grew up in and, and the only thing I don't like about LA is the relentless good weather. It's not writing weather. You know, this is why the Irish, right so well, I believe, we never we never every once in a while we were at UCLA, we would admit an Irish writer, somebody applied from Ireland. I worked with an Irish writer who wasn't the genius. And I'm sure it's because of the rain, you know,

Alex Ferrari 21:40

there it is. There it is. Now, so speaking of, you know, young writers, you obviously worked with a ton of young writers in your program. What are some of the biggest mistakes you constantly saw young writers or writers who are just starting out make

Richard Walter 21:54

young writers make the same kinds of mistakes that old writers make? I want to say something about young writers. So we are the the program that I taught was a for the most part was a master Fine Arts, a graduate program. So most of the writers were a little older, and then we actually tilted I had a pro age bias. I like to bring in older rather than younger writers, people who had experiences that are worth writing about other than the funniest prank they ever played on the Resident Advisor in the dormitory. So yes, it's true. I lectured to undergraduates. But it was not a typical class. It was generally people were more among undergraduates at a at a college. But people were generally more mature. The single biggest mistake writers make including this writer who's talking to you is we write too much, too much language, too much description, too much dialogue, too many pages, the scripts are too long. I like to you know, I'm I'm a retired college professor, I was over 40 years doing that, and I kind of have an occupational hazard. If we could call it that. I can't help myself. I sometimes just stop people in the street and give them a pop quiz. So here's one for you and anybody who's watching us, don't worry, it's just mobile choice three answers. How long should a movie be? Should it be a too long be too short? See just exactly the right length? The answer is be too short. If you're on a vacation, and you're ready to go home, then you were there too long. You should be reluctant to go you know, last summer there was a racial reckoning and a lot of protests all across the nation. A lot of people were carrying signs that said enough. exclamation point. Did they mean enough? No, they meant too much. You know, somebody says Enough already. They mean they don't mean enough they mean they mean too much. Right? So if you're if your film is ready to end then it's it's too late. I'll also say this and I think this is sort of original with me the the three act structure it's it's our song never called structure just got the beginnings middles in and and and that applies not just to the beginning, you know, is the beginning is the part before which you need nothing. And the end is the point after which you need nothing. When I tell that to audiences, and the classes I usually take a pause then because I wait for somebody to say what yours is that you just told me that the big there's nothing before the beginning of something after the end. I have a dog that knows that. And yet I see movies, right? That stopped before the big let's go on after the after the end. I am a spike lee fan. My favorite movie my spike is actually x i think it's it's the the Malcolm biopic. Then A Washington I think underappreciated what a terrific actor he is a lesser actor would have been chewing the scenery but that's, that's not the way Malcolm was. But any event, one of the spikes really, really good early films. I think the one that made his reputation is do the right thing and do the right thing at the end it ends you know, Danny Aiello is the pizza owner and spike explain mukhi who works in the shop, it's one of the few establishments in the neighborhood that had offered a job to anybody and the brothers industry to that they're resurrecting that, you know, they're they're, they're, they're in an interaction, they're, they're writing they're losing they're they're burning. And spike mukhi is trying to figure out what to do and he finally decides to join the should he protect the pizza are, you know, guy, his boss and independent entrepreneur trying to scratch out a living there? He doesn't seem like a really evil die. Why burn down his story, you know, on the other hand, it shouldn't be with the brothers and and joining the movement and so on. And he did and he chooses the latter. Spike says he wasn't endorsing violence, he was just asking the audience to, you know, decide for itself what's the right thing, I'll give him that. But it's clearly the end of the movie and it doesn't need it fades out, you know, he's he throws the the trashcan, trashcan through the plate glass window, and it fades out. Now you can expect the credits to rolling and now it fades back in and this spike. And then a yellow, the pizza owner, the store owner, side by side and and they're having a discussion. And there's a croal from from Dr. King about non violence. And then there's a crawl from Malcolm about violence. And I'm waiting for a crane to lower Ted Koppel or

I don't know if that couple of names that they pick anymore. But he was a he was a like a news anchor who would moderate and facilitate discussions. And so I mean, this is going on and on after the after the point before which you you need nothing. I'm arguing that not only to home movies have places before which you need nothing. And places after which you need nothing but so also the new parts of movies for example scenes, even parts of parts like lines of dialogue. I remember, I was talking before about the Meili, as I mentioned my old classmates to classmates, George Lucas, chameleons, john, as he became very successful. Went to direct I think it was his first movie. And it was the first movie that he's gonna direct he had written some very successful movies. We wanted to direct and so he was directing Dylan ger and kill injure starring Warren Oates. rest his soul Warren gone now decades, not only a very good actor, but a really, really nice man. miss him every day. So john put together the rough cut, I wasn't even a rough cut was like an assemblage of the movie. And he invited a bunch of us in former classmates, half a dozen, maybe eight people, including George. And I remember to, you know, to look at the film and to comment on him on it and give them advice. And remember George saying, john, you don't need to show the cop pulling up. Turning off the you know, hand turning off the ignition, getting out walking across noggin, you can jump around, you can move around in ways that that maybe in the earlier days, you could not audiences, the more savvy and now they're they tip HIPAA to the to the literate, they're more literate, or cinema literate, or they hate to use the word cinema. Let's call it movie literate. And likewise, that applies even to lines of dialogue, you know, any line of dialogue that starts with, with, you know, or I've been thinking or I think, or it seems to me, that's before the beginning. Or at the end of a line, your main character might say, Monica, and I really mean that, you know, that people say to me, and I'm always saying no, no, that's after the and that is after the point after which you need nothing, by the way that test for that is very easy. You just imagine it's not fair does it? If it still makes sense, you didn't need it? If it all goes to hell than then you need it. And it's just so easy to know what to do. It's hard to do it. Because of the reason we said earlier takes a bunch of a bunch of time to do that. So once again, people will say to me, when I'm telling I'm telling you know, you got an urge you got vocalized pauses, um, or, I mean, or I'm thinking all of those kinds of things. I'm like that I you know, the way people people talk to this played on the language the I'm like, yeah, so I'm like, and he's like, and I'm like, and he's like, so somebody will say, I'll tell people No, no, no, no. You know, get rid of And you can guess what they said to me, they say, but that's the way people really talk.

Alex Ferrari 30:07

We'll be right back after a word from our sponsor. And now back to the show.

Richard Walter 30:16

Well, is it the way people really talk? Absolutely. Yes, it is. So what's wrong with that? Well, two things are wrong with that. The second thing first. The second thing that's wrong with that is you don't need to go to the movies to hear the way people really talk. You just go out

Alex Ferrari 30:31

on the street. No One No One talks like Tarantino's characters. No, but

Richard Walter 30:36

I mentioned Jerry Lewis, you know, if you say, Hey, hi, how you doing? You know, Mazel. Oh, pretty good. You know, I am now taking walks. We've been in lockdown for a year, I can't tell you enough for a retired professor. The question is, How does he know the difference? You know, the, you know, for a writer, it's, it's a terrific excuse not to go swimming. I'm a swimmer, not to go to physical therapy. I go to physical therapy. I have arthritic issues. I'm just kind of kind of liking that actually actually liking the isolation and, and, and so on. But I mentioned Jerry Lewis, if you asked, when you when I take walks around the neighborhood, and I see. Hey, hi, how are you? Nice to see you night. Yeah. Oh, yeah. Hi, you know, kind of masked and distance and everybody kind of greeting each other. If you say that to Jerry Lewis, of you, Hey, how you doing? He said, Well, I have a rash on my crotch. The truth is that you do not need to go to the field of the pay that for that second of all, but first of all, the way people really speak violates the single most fundamental rule in all of it's the only rule you ever really had at UCLA. You can do anything you want. As long as you don't violate this rule. And I can say the rule in three words, right? Here it is, don't be boring. The way people release because boring. Hey, how you doing? Oh, not good. Boy, you believe that it's really clouded and thank God it has been so dry here. Now we've had a number of drop lab like yakka kid to teach every single line of dialogue that any character speaks in Alliant has to in a screenplay has to move the story forward. It's just as simple as that, again, very easy to understand. The question is why does it really do this? And and the answer is they just will not give it the time. Somebody said to me the other day, I gave the agent. I gave it to the agent two weeks ago in under two weeks to blink of an eye. Now. Somebody said to me the other day, this is my fourth three, right? Well, one of the most you mentioned the gym owners you mentioned, Paul Castro, I certainly rejoice in in being able to brag about about having worked with a lot of really, really famous writers. Now, of course, I'm not bragging, I'm bringing them out, bragging about them. One of the most successful writers I've ever worked with is David cap. Oh, yeah. He EP EP, he's so famous now that people pronounce his name correctly. It's not cope. It's a cap. And he says this, he's written several, at least three pictures to Stephen, maybe four. He wrote at least two of the Jurassic Park's he wrote War of the Worlds. And and I mean, it's just the gigantically successful writers also very good director. And David says, The secret of his success is 17, the number 17. And what does it mean by that? I mean, that's the number of drafts that he goes through. before he's really, really, really ready. So once again, you want to succeed is right, he got understand two things, essentially. One is that and a lot of writers don't get this a screenplay is only two kinds of information. It's an elaborate list of only two, only two kinds of information. Anybody want to know what they are, they aren't what you see and what you hear. From the point of view of the right it's what the actors do and what they say. From the point of view the right I mean, there's a lot of sound in a movie, but from the point of view, the writer it's almost all dialogue. I can't tell you how many times I see descriptions with somebody remember something describes how they feel what their mood is interior internal mental processes and what what does that look like? Your hair we realize is that the gun is that when I'm sitting in a movie theater, looking at a screen, the job of the writer is to replicate for the reader of that script, the experience that will be had by somebody sitting in a movie theater watching it unfold on the screen. So You can tell me the reader that Joe realizes that the gun is in the nightstand. You know, at the motel when I'm trying to imagine somebody sitting in a movie theater looking at the screen, how are they getting that? So that's the first thing you got to recognize. It's just sight and sound. By the way, in final draft, the Rolls Royce, of

screenwriting software is creating a Richard Walter template, you know, you can get different templates if you want to write for the script for the Simpsons, you can go to the template list and menu and hit Simpsons it'll come up or like, the Simpsons office likes it, you know, what they want from me. And among other things it's going to have is in descriptions, wide margin, if, if there's a word like realizes, thinks, remembers, feels any internal mental process like that, it's going to be highlighted, do you really want to? Do you really want to sell That's amazing.

So the trick is, again, first of all, only sight, the sound, what we see and what we hear and don't say we see. Because if it's in the wide margin, we see, right? That means we see you don't have to say what what you don't have to say, you don't have to repeat yourself. You don't have to repeat yourself. You don't have to repeat. If I say that three times, and yet I see I see repetition and the script to go on. But much worse than that. So that's the first thing sight, sound. And next thing I've already said palpably, measurably whatever half happens has to move that story forward. And that's it. If you'll do that, it doesn't matter what the scripts about doesn't feel close genre. Doesn't matter what happens. It Matter of fact, you can even have nothing happen. And if it's integrated, that is safe, it moves the story forward. Even nothing happening. Will will attract an audience and work effectively in a screenplay. Now how can that possibly be that nothing I will give you an example from from a writer that I worked with years ago, he's only won two Oscars for Best Screenplay. I'm talking about Alexander Payne. My favorite picture by Alexander is about Schmidt. I think it's jack Nicholson's best work in his entire career. And the very opening of that picture, it's Omaha office building, we're in an insurance office. And there's jack nicholson playing Schmidt and he's sitting at the desk. And he sitting Stockstill is not doing a thing. And he's all alone in there. And he's saying nothing to anybody on the phone or in person, there's nobody there. He's just sitting there. And we have a little bit of time, in which apparently nothing's happening. I mean, if nothing happens for three, four or five seconds, that's a long time. And it's longer than that. But during that time, we'll get in a look at the office. And we see that all the graphics are off the walls, we see that all the shelves are clear, we see that the desk is absolutely bare, we seen in the corner of the office, stacked up very neatly cartons, packages, boxes, that obviously contain all the stuff that used to be on the shelves and used to be on the walls and so on. Clearly, just looking at this, we see that this man is retiring. There's no motion in the same except for one thing, there's a round clock with a sweep, second hand, and that second hand is ticking off two seconds, and is about 25 seconds to go until it hits five o'clock. It's just 25 seconds before five o'clock, and he just sits there. And then when it hits five o'clock, he just gets up and walks out of the room. And that's the whole scene. So it's kind of a scene in which nothing happens. But Wow, how much information do you get in that scene with supposedly nothing happened? Right? You realize this is a sales. This is a an insurance guy. This guy is his last day he's retiring. Maybe he's a stickler for detail. Nobody would have cared if he left three minutes earlier. Matter of fact, that's his last day. He probably could have left before lunch, you know. So did he stay there because he's methodical and punctual. Or did he stay there because he he's been waiting to retire but now he's actually afraid he and I don't know too many people who, whose life's dream is to become an insurance salesman. So maybe this wasn't his dream. And he's always been hoping once he's done with this, he could get creative and write a novel or a poem or become a painter or something creative. His excuse for not doing that was he had the job now suddenly, he he's about to not have the job and really have to take responsibility for not being creative and being creative as he may be. It's a really great character issue. And that, that we're not sure about that that leaves the audience wonder about that his testimony not to the weakness, but the strength of the writer, Alexander Payne and that scene. So you can see how with absolutely nothing happening. The story is driven forward. And well, you can do whatever you like, all the rules are off if it's integrated if it moves the story.

Alex Ferrari 40:27

Now, let me ask you, when I always love asking this question is, would you recommend starting with character, or with plot? Because I know a lot of there's there's two different camps here. So we'd love to hear your point of view.

Richard Walter 40:38

People ask me all the time, what do you think is more important character replied? And I answered them with a question. What do you think is more what's more important to you that people say, Richie, what's more important your character or plot? And I'll say, what's more important to you, your heart or your lungs? You can't talk about character and plot as if they're separate things. The richest character in all of English language, arguably, world dramatic literature is Hamlet, arguably, I mean, you know, certainly he's way up that they were volun libraries full of volumes, analyzing junk, us his character, and, you know, in detail, just that one aspect of the play his character, Is he mad? Or does he feign Madison, this and that the other thing? Do you remember? Have you read the play? Do you remember the description the playwrights description of of Hamlet? It's three words Prince of Denmark, there's nothing about melancholy. So who is this guy? And the answer is he is what he does. And what he says just like you, just like me, like everybody who's who's who's listening. It is. There's, there's a wonderful book, very underappreciated very little known by a writer named Millard, Calvin. called claps and characters. And by the way, it's plots. First, Aristotle also puts plot story in front of character, I, like, I think it's a mistake to to put them in sequence at all, I think they all operate together. And, and, you know, when, for example, when, when I was going to say about Miller's book, this is one of the wisest things I've ever heard. It really tells you all about dramatic writing, but also about life. And here it is, again, not original with me. It is action that defines character. and not the other way around gonna say it again. Action defines character, not the other way around. What does this mean? In practical terms for a writer, it means you should not figure out in advance who your characters are, and what kinds of people they are, you know, I attend lots of over my career, I've been to gazillions of writing festivals, and every once in a while they have biography workshops, character biography, workshops, where you can just outside of the context of a story, you can invent characters, and list them and so on that presumably you will use someday in a in a screenplay. Now. I tried to be polite, and courteous, just generally in my life. And when I hear about stuff at conferences like that, I'll say to people Oh, that is SAS, SAS. Sounds interesting. But in fact, I think it's a bunch of bullshit. I don't think you can invite you can invent characters are meaningless invite characters outside of the context of story and story being what they do and what they say. In other words, what I'm saying is, don't figure out your characters. Watch what they do, they will tell you who they are. Just like you know who you are, based on what you've done what you've said,

Alex Ferrari 43:55

right? So So let's say perfect example, if someone's writing a description of me, I'm the hero of this play, or this this screenplay that we're writing, right? And it goes, Alex, where's a hustle hat? His mid 40s ruggedly handsome, obviously

Richard Walter 44:17

much better looking than this Congress shows, but not nearly as good looking. As you

Alex Ferrari 44:21

say. I appreciate that, sir. Nope. So basically, I've seen and I've done this myself in my writing is I will see this long description of like, and he has this and has done and has this and you could and I think I personally feel and I love to hear you think i think that's a waste. I think what what you just said about Hamlet was so perfect. Because if Hamlet in the next IV goes Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, if in the next moment, he kicks a dog out of you know who he is in a minute, without saying he is going to he hates animals. He's a mean got no, no, he kicks the dog. And that

Richard Walter 44:57

does that. Right? Yeah. Exactly right the I've you heard me say, and I've said it throughout my career. The big I just said at moments ago, the biggest mistake we make, as writers, including this writer is talking to you is we write too much. The most common place I see that is in character descriptions, I've read character descriptions of what kind of a candy bar she would eat. If she ate a candy bar. Though she doesn't need a candy bar in this in this film, what kind of a tree she would base, a willow. There are only two bits of information that you want to establish only to when you present the character. And remember, we're trying to replicate in that screenplays experience that will be had by the viewer in the audience, okay of the film unfolding, not somebody reading the script, but watching the film on the screen. The only thing is we want to know about the character in the description is our gender, and age. That's it. And by the way, that's a good reason to use gender specific names, not to use androgynous names. Chris Robin, so on again, unless it's integrated, integration, moving the story forward will tell you what you need and what you don't need. For example, there is a famous character, Pat.

Alex Ferrari 46:26

Yeah. And Ron is

Richard Walter 46:29

created by Julia Sweeney on SNL. And she does a bit called it's patently made it into a feature movie, it's packs, well imagine that they said it's Patrick. Or it's Patricia would ruin the whole thing. We needed the Dr. Yunus name there, because the whole point is progeny. Now, imagine, you know, I have a friend who is a woman but used to be a man. She is a trans. And I mean that the whole hog she she has had what they call gender reassignment surgery. Now, if you met her, you wouldn't know that. I know that because she's an old friend of mine. But if you were presenting her new movie, you should give her a feat she's going to present as a woman in the movie, you got to give her a woman's name a name, that's clearly a feminine name. If if it'll be clear enough on the screen, oh, that's a pretty young woman, which is what you would think of this woman if you met her in the street, or you saw her on the screen. But on the in real life, and on the screen, you can see all that to a woman but from the name on the page. You can't tell them unless it's a gender specific name.

Alex Ferrari 47:44

So specifically in that, in that case, I think a mistake a writer would make is like, this trans woman, Pat, is that would be the description, which was an absolute mistake. Because

Richard Walter 47:56

absolutely, it would be like telling the punchline to a joke.

Alex Ferrari 47:59

Right? Exactly. So as you're as you're reading the screenplay, as you're reading the screenplay, if you're if you're watching it on the movie, if you just use that analogy, which is so perfect. If you're looking on the movie, unless someone says something or a specific if that's presented as a woman that characters presented as a woman, it's a woman. And as long as it looks like it's fine. If you look, there's a reveal later. I mean, the crying game obviously is that great reveal, but the whole movies you know, that's kind of part of the game. But what but

Richard Walter 48:24

but there's there's an actual movie, it's good example you might have seen, it was pretty well known it must be 25 years ago, the crying game. Yeah, that's what I just said, in which this one character appears to be female. A very important very central character in the narrative. But midway through the movie suddenly, and it's a major turning point in movie it is revealed that this is actually biologically a man. Imagine if at the beginning when you introduce her as a woman, you put power and suddenly By the way, she's really a man, we'll find out later she's a man. Well, that's like opening upon a joke by telling the punch line, right? Telling telling the joke. Once again, you want to reveal the you want to reveal information in the same way the audience is going to get it. And that is limiting. It limits you to the to the ever present numbing, present tense, you can't say what happened, what will happen and you can say that in a novel, and you can't say what anybody's thinking or how they're feeling. But you as you can in a novel you've got to stick to just sight and and sound and you have to reveal the information to the reader at the same time as it will be revealed to the viewer sitting in the audience watching the movie on the screen.

Alex Ferrari 49:40

So when and that's so that's so great. And I've never really thought about it the way you've presented it which is like it's it's literally the screenplay is the representation of what you're going to see on the screen, which is on the face level. Everyone knows that. But yet like you said, not everyone does that. So when you the other problem I see a lot of times and I I was when I first sent my screenplays to get coverage years ago, I would get this note back on the nose dialogue, oh my god knows unlost dialogue and just kind of like I think we've been talking about kind of like on the nose descriptions, which is also, you know, rampid in it.

Richard Walter 50:17

The trick is to get the mind working, you know, not just video games and computer games are interactive, all art is interactive. And the idea is to engage like gears, engage, you move this and it moves that. And the way you do that is not by putting out a lot of information, but by withholding a lot of information. The, you know, all all I remember, years and years ago, well, it was it was around 1999 with the new millennium coming upon us. The I was asked, it must have been a slow news day, because because the the press came to me and they asked me, you know, I have a fancy title and I'm good with sound bites. So I would on slow days, news days, I would get asked things. And I was asked what is the reporter called me up and said, the new millennium is coming. The decade is almost over what was the best picture of the nine days. So for a moment, I thought to myself, gee, let's see, what did I like? I'm not a buff. I don't see all the movies. But what did I seen in the 90s? That was really, really good. And I couldn't think what was movie and was this tonight? And suddenly it dawned on me I had actually one of the single greatest insights that I've ever had in my life, in the midst of struggling to figure out what movies when the 90s what was best movie in the 90s it occurred to me that in this entire universe. And they tell us that there are infinite number of parallel such universes. And it is so gigantic. In fact, since we started talking, it's already like 3 trillion times larger than you know, than a 20 minutes ago. There is not one thing in all of that vastness. There is not one item that is less important than what I think is the biggest movie in the nine days. That doesn't matter what I say I should stuff work into i don't i guess blurted out, terminated to. Now why did I just terminated due for a couple of reasons. For one thing there, I'm a college professor. I'm a film professor. I'm a full tenured professor, you know, they expect me to say there's some garion tone poem. They don't expect me to choose a big Hollywood franchise the second chapter. So I'm trying to be a little outrageous. And so should you if you're writing a screenplay, I'm trying to be provocative. I'm trying to be interesting. If anybody said to me, oh, you're just trying to get attention, I would say, found me out, you know, I mean, that's what every screenwriters is, is trying to do. But there's another reason that I chose terminated to. It's a really, really good movie.

Alex Ferrari 53:06

It's a good script to I mean, camera

Richard Walter 53:07

cameras. Well, the cameras movie if it's not a good script, it can be a good script than a bad movie. Yeah, but it can't be a good script, a bad script and a good movie. More about that maybe a little later on. But if you remember, Terminator appears, you know, he comes out of the sky. And if you've seen the movie, he just lands up naked on the lawn, in this, you know, in the boonies out somewhere in a very rural area along a highway where there's a biker bar a lot of choppers parked out in front and he wanders in stark naked looking around and they're all looking at him I'm looking at it's crowded, it's shoulder to shoulder with with with tough guys. The kinds of people that go to biker bars. And he's kind of gauge and you can see from his point of view, is he measuring people and now he sees one guy who fits him who's exactly his size and Arnold's a big guy. So this is a big guy, and it's a guy shooting pool. And he steps up to that guy. And he says to the, he says to the guy, give me your clothes and your motorcycle. That's a pretty good Arnold.

Alex Ferrari 54:18

Those are fantastic. I was gonna say.

Richard Walter 54:22

What does the guy say? Now? I'll tell you what he doesn't say. He doesn't say Are you out of your mind? You naked Australia's you stumble in here and you think I'm gonna give you mine? He doesn't say any of that. Does anybody remember when he says I'll tell you what he says. I remember the line quite well. Again, Arnold. As terminate says to him, give me your clothes and your motorcycle. And what does he say? He says, Yes, I got to say please write. Much, much better. And by the way, on overreaching, he like gets ready to beat him with his full kill. He grabs his collar this lifts him up in the air. The way I could lift you know, this hat, you know, he weighs about that much to Arnold. And by the way, he has What does not happen after that. What does not happen after is that it's a fight, he grabs his clothes, he puts the clothes on, he goes out and takes him out now, he grabs me lifted off the ground. Suddenly, the very next frame, he's on the highway dressed in that guy's outfit, and he's shooting down the highway on the bike

Alex Ferrari 55:26

after after a slight fight scene after a slight fight scene. Yeah,

Richard Walter 55:29

really any fight at all? Yeah. And a lot of people will let you know, worse writers and worse directors, Jim Cameron would would have had a big fight, fight there. Something like you're out of your mind that's on the nose. You're not going to give you my clothes. But you forgot to say please is subtext. It really means something else doesn't that old jokes work that way. Here's a quick joke. Maybe you heard it. The doctor says to space, I've got bad news and worse news patient says, well give me the worst news first. He says, well, it's cancer. It's metastatic. It's everywhere. It's inoperable. You don't even have six weeks to live. That's it? Oh my god. What's the news? Not? Not quite as bad as that? Is we got Alzheimer's disease. So the guy says, Oh, my God. Well, at least I don't have cancer. why people are just getting it.

Alex Ferrari 56:28

It took me a second. It took me a second to get them. Yeah,

Richard Walter 56:30

I got to the point. Is that it?

There's nothing funny about cancer. I know people struggling with that. Why do we laugh at that? Because we're monsters and eat? No, it's because we're human beings. And when we feel stress from text, something that we heard, and then we figured out what it is Oh, I know. Now I know what it means. There's a release of that stress. And it comes out as as as laughter so so once again. It's all jokes work that way. Every single Joe here is is another Alzheimer's joke. A couple, elder elderly couple, they walk down the street, they encounter this other couple. Hey, we haven't seen you guys in a minute. What are you doing over here on this site? And then well, we just had lunch at this restaurant, we read a review. It's a new restaurant. And we read a review a time to go we wanted to try it out. And we did and it's really very good. It's Oh, well, we were gonna have lunch. Maybe we'll go there. What's the What's the name? What's the restaurant? What were the guy says, Oh, it's called the? This happens to me all the time. We were just there and I can't eat. He turns to his wife. He says, He says do you he says help me with this. He existed the guy who's asking them about the restaurant he says help me with this flower? Red thorns guys is Rose. He's it? Oh, yes, of course. Rose. That's what it is. And he turns to his wife. And he says rose. Do you remember that mister. Okay, once again, why the left, because you thought this and so. So that's what we want to go for. We don't want to be on the nose, we want to say what's underneath. And the best thing if possible, the most articulate thing that you can say is is nothing at all, I'm going to give you one more joke also about health, the two to 2x two examples of the difference between being old and being young. And maybe a large part of the group that watches this is too young to get this but difference between being old and being young. The first difference is when you're young, you go to the doctor, sometimes when you're old, you go to the doctors. I mean, I I am old enough now and I go to if I'm going to send an email to one of my doctors and on the on the email site, you know, the the health site that I belong to at UCLA. If I hit the little down arrow, if I say want to send the message to my doctor, then it'll say witch doctor and you hit the down arrow. The menu falls down with all the boxes that I have. I mean, it goes down through the bottom of the computer out onto the onto the desk. So there's the first one hitting them. But here's the second one again. difference between being young and being old. The first one I already told you here's the second one when you're oryza. When you're young, you go to the doctor when you're old, you go to the doctors, okay, also when you're young, you get sick and then you get better. See now people are waiting and they're waiting. See by not saying it. You've called them you've drawn

Alex Ferrari 59:47

interesting.

Richard Walter 59:49

In business and in art, if you chase after people, they run away from you. Yeah. If you want them to come to you, you got to withdraw. I bet you've seen the Devil Wears The first image that magician that they call Meryl Streep, she won her third Oscar, best, best performance for that role. She plays a very powerful woman, really, really powerful, powerful woman. She never raises her voice.

Alex Ferrari 1:00:22

Never, never.

Richard Walter 1:00:24

She never talks louder than this that makes people lean forward. Good, engage, listen closely. If she's, that might seem powerful, but it's not nearly as powerful as going the opposite direction. So that's what I'm always telling writers, writers to do. Less description, less noise, the more you put out there, the less opportunity there is for the audience to engage.

Alex Ferrari 1:00:51

We'll be right back after a word from our sponsor. And now back to the show. Now, what suggestions do you have for creating conflict within a scene?

Richard Walter 1:01:07

Well, I mean, it's funny, my my old teacher, the legendary long deceased or when are blacker, he want George he took millions he put a lot of people in a seat. He used to say, Where do you need conflict in a screenplay, one that every to answer in unison? And he also would say, before you answer, I want to tell you that it's a one word answer. Where do you need conflict? And scribbling? The answer was, everywhere. Everywhere. Everything could be a conflict. It doesn't have to be a, you know, world war three and everybody battling each other, although that's okay, too. But people should not be getting along. There should be dissonance and discomfort. And so I'm hearing about now people there's, there's, oh, there's a new institute that wants to make it possible wants to support film, filmmakers who want to make films that have positive social impact, and uplift. Well, if you want, if you want to have social positive social impact, and uplift, you are doomed. You can't you might have social impact, positive social impact, but not by trying to have it one of those violent series that I've ever seen. And it's also I think one of the greatest works of genius in all of Western civilization is breaking bad. I'm a big, huge fan of breaking. I don't I've never seen anything better than Breaking Bad. Have I ever seen anything as good as that? Yes, the sopranos, that godfather. But I've I've never seen anything including Shakespeare's plays in the great Greeks. I think it's one of the great Masterworks of dramatic literature Breaking Bad. Now, I am somebody that I don't want to get too political. But there has been a I think one of the greatest tragedy. One of the very greatest tragedy the last half century in America is the abandonment of support for public education. You know, when I came to UCLA, people don't know it's all paid for the the state but know that back then they paid for about 1/5 20% back then, and now they pay for about half it's about like 11 or 12 12%. Worse than that, though, is public school. K through 12. somebody my age, I went to public school in the 50s. The, you know, somebody, somebody like me. We had really, really good schools. And in fact, my wife and I were married 53 years, we 54 years and come come June. That's pretty typical. By the way, I have to say, for my generation, most of the people that I know, it's not all that unusual. I only mentioned it because we are college sweethearts. We went to the state. We went to a State University, we met in college, upstate New York, what is now called Binghamton University. Harper College is just the undergraduate wing of the Binghamton University. It's part of the state interest in New York campus. And it's virtually free when we went there. It was $400 a year. And and by the way, if you got a region scholarship, and both of us did, and most everybody that we knew did, it was pretty easy to get to read. And it was it was absolutely free. Wow, raking. What can that possibly have to do with Breaking Bad and by the way, it's nice in movie narratives to have something that doesn't seem to be connected to anything that suddenly gets connected. And I think in teaching, I tried to do that as well. So I've been talking about the abandoned in the public schools and talking about breaking bad. Well, undergirding the whole series of Breaking Bad is this question Why does in the United States of America in Albuquerque, New Mexico, does the high school chemistry teacher get 43 $1,000 a year and have to work at a carwash. And then when he gets a fatal diagnosis has to become a drug dealer, a drug manufacturer and drug dealer just to provide medical coverage for his for his for his, his family. So I think Gilligan and his writers, Vince Gilligan, I'm talking about the creator of Breaking Bad, is contributing very, very palpably, very measurably meaningfully, to a very important political issue. But he's not trying to rise. As soon as you try to do something, you will fail. I was thinking the other day about this, imagine you're standing at the edge of a big field, big grassy field acres and acres and you have a baseball. And you throw it from the edge of that field just as far as you possibly can.

You You're a younger, more fit guy, you probably throw a little further than I but I bet we could both throw it about a block, let's say, half the woodlands magine Atlanta bounces a few times. It's some fencing and it rolls and finally stops. Now you walk up to that. And before you pick it up with a big fat piece of yellow chalk, let's say you draw a circle around it right? And now you pick up the ball and what's there there's a circle indicating exactly where it landed. Right? Okay, now you go back to where you threw it previously. And throw it again and make it land exactly there. Exactly. There. You'll never do what you do 10 dozen times. It's, it's going to come close. Right? But it's not likely ever to get right to that spot. Why? Why not? You just did that without even trying you were able to do that. And now you can't do it at all? Well, that's the answer. You were trying. As long as you're trying you will never you'll never succeed at it. And too many writers trying too hard. They they have. They have not? Yeah, I was gonna say they lost the ability. But I don't think it's an ability that you have, that you lose. It's an ability that you have to acquire and have to find the ability to stay open to the surprises to be a little confused about what's happening in in, in your screenplay. Yeah, not to nail everything down. But to live with that dissonance and with that, without knowing

Alex Ferrari 1:07:22

it. So it's so funny, because I mean, after now 450 probably like between all my podcasts like 500 or 600 interviews, I've done it over the course of the last five, six years. I've talked to so many amazing people. I've noticed that, you know, you hear these mythical stories of like, let's say, you know, when Shane Black was selling a house was selling those scripts in the in the glory

Richard Walter 1:07:44

days de la UCLA, but keep going.

Alex Ferrari 1:07:46

Yes, exactly. So all these kind of, you know, mythical Tarantino, all these kind of guys, who are these mythical kind of screenwriters. When they weren't like When, when, when quitting wrote to romance, he didn't know it was going to be sold to Tony Scott, and then turned into the movie. And when he wrote Reservoir Dogs, he didn't know it was going to be what it was, he wasn't trying for that he was going to shoot a small independent film for 50 or 60. Grand, and get it done. It just so happened, and run my own career. In in my own thing, I've tried to chase that thing, like I want to this is gonna do this for me, and you start going and never, ever works out that way. Because there's because life doesn't work that way. And you have to be open to the, to the things like when I started this podcast, the screenwriting podcast specifically, I just just kind of threw it out there. And I wasn't expecting much from it. And then slowly, but surely have built up steam. And then all of a sudden, people like yourself, and all these other amazing guest started showing up. And I'm like, but I didn't plan on it. Like, you know, my goal is to get when I started, my very first step is to get Richard on the show. Like, no, it just kind of happened. And it kind of flows that way. And you have to be open to that. And when you're writing, I agree with you 110% if you're writing with an outcome and in in mind, you're more likely going to fail. Is that a fair statement?

Richard Walter 1:09:09

Yes, I will tell you the the I've had really three phases in my development as a writer relative to the story. And I do think story is what it's all about. Story encompasses everything else story, his character story, his mood setting, all of those things, you know, come come out of this, this thing that we that we call story. I am a trained actor. And I'm a very experienced public speaker. Not only have I lectured 1000s of times on Khan campus and off campus, but I also had 15 minutes of fame. It was really 15 years I was constantly on all of these talk shows. The O'Reilly Factor I was like the the unofficial house lib for Fox News. But I was also I must have done two dozen visits with chris matthews at MSNBC Sure, you know, commenting on on various kinds And I, the reason I mentioned that is I can say things very convincingly, even if I don't believe them. And I'm going to say something now very much along the lines of what you just said that I do not believe what I'm about to say is a hoax. It's a lie, I don't believe and I've just told you that. But people watching this, I'm gonna say until convincingly so persuasively, it makes such sense, they're going to believe that it's true and that I believe it even though I've just told you that I don't believe it. And here it is, if you want to succeed in a competitive enterprise, and there's nothing more competitive, I mean, what's more competitive than than screenwriting My God Jesus, you know, where where, where trafficking in our own imagination with selling our daydreams for money, welcome, be no better, better fun than that, you know, we get we get paid for, for what other people get scolded for, you know, which is, is daydreaming. If you're going to succeed in something like that, you have to focus. You can't be given over to distractions, you got to have a laser like focus towards that make great sense. But remember, I told you, it's bullshit. The fact of the matter is that your best bet is tumbling, stupidly and blindly along and bumping into things, from time to time making stuff available to things that you love, and you hang on to and you grab onto and you hold on onto that thing, things that surprise you or things that you didn't anticipate in your life narrative. Remember, I came out here I was going to go back that eventually I thought maybe I'll be a lawyer or something like that. I just let circumstances unfold. And what I've discovered again, is it with resin that's the life narrative in your story narrative. Likewise, it I used to think it was about there's a line of time you know, about an hour and 40 minutes most movies are too long. The narcissism of directors they just won't get off the stage. Look at me look at me. It's supposed to be invisible. It's supposed to everybody knows it's a movie is supposed to hide that fact from the non announcement, not proclaim it to them. Don't get me started now on what I call amateur chic. The new kind of directing with everything handheld and 360s directors calling attention to them selves rather than then then trying to hide the the goals will limit you they they will you know, man.

Again, the the story. I used to think there's the 100 minutes, and you have to put things in there then I thought the next phase was no, no, no, no, no the things that they are. It's about taking things away. I kind of think of I like to talk about Michelangelo, sculpting the famous statue of David that Stan, Florence, right. He says that there was this big block of marble that his workmen brought down from his favorite quarry in Carrara. And he looked at this big hunk of stone and he could see inside it, the David and all he did to create the David was to take away those parts that were in David, of course, knowing how to do that. How to and which parts to take away is the difference between rank amateur and genius, but it is a taking away process. Art is and story creation is and I have crossed paths with with you know I have a lot of experience myself as a writer that's taught me a lot. The Wall Street Journal calls me and I've memorized this now a writer have substantial professional experience throughout the media. There's no kind of literary laundry that I haven't taken in but my experience as a writer is leveraged by the 1000s of writers that I've worked with on campus and off campus as a screenplay analyst. And as a professor teaching this subject, and I've never met one writer, not one writer, I promise you there's not one writer watching this podcast, who has not had the experience of hearing a character say something apparently on her own, you know, as if he invented it by herself doing something that you never that the writer never expected. The story taking a twist or a turn that you didn't expect somebody else becoming the protagonist. The major mistake writers can make is to try to drag back to an earlier notion that they had rather than than allow those kinds of things to happen. You know, I like to tell a story about common Hagen's. He was a UCLA student before my time. Now DC stressed his cell and I think Australian, but he his first picture was Harold and Maude. went on to become a director and a writer director. He did wonderful films. big Hollywood films. Silver Streak, foul play. A these are really really wonderful, wonderful films. Collin told me 1000s of years ago when he when he was a student at UCLA that he hoped to win first prize in the golden competition. First prize was 40 $500. How they came up with that, I don't know. But that was enough money at that time to live pretty comfortably a student on his own for a year in LA and he would just be able to write that was his goal. When the goldwin not have any day job. no distractions just sit down and write, but he didn't win first prize, he only won second prize. And second prize was 20 $500. So he knew he needed a day job. And so he, he took the perfect actors or writers day job, not a cab driver, not a waiter, but he went to work for a swimming pool cleaning company. And the very first home he comes to the clean is in the flats of Beverly Hills, very wealthy area where a lot of movie people live. And he's vacuuming the pool behind the house. And a man comes out with a screenplay and sits down under an umbrella. Again, like a beach umbrella in the shade to read this screenplay. And it's clearly the guy who owns this house. And so common gets to talking to him and tells him that he's himself a writer and and he's written a script to get this guy to agree to read his screenplay. And sure enough, he ends up producing Harold and Maude and it launches. Comments career, and common says to me imagine if my dream had come true if I'd met my goal, which is if I'd won the Golden prize, first prize as I plan I'd be cleaning fucking swimming pools today, you say? So you got to give over to the circumstances and happenstance. every writer I have written in screen. My screenwriting books is playing God I call screenwriting the god game just as God created the universe. So also does the writer create the universe of her screenplay? You want it to rain it rains, you want it to be sunshiny sunshine, you want to kill somebody, and who has never wanted to kill somebody, you can do that in a in a in a movie and then if you feel remorseful about it, you know you can actually bring them back to life.

So So once again, it's it's a it's a question of surrendering authority, not seizing it, but but surrendering it. And and once again, staying open to the surprise is the very first script I ever wrote, was in a class at or in Irwin, our blackness Professor blackness course at UCLA at USC all those years ago in the in the 60s. And when I got finished with that draft, I realized the first draft, I realized that I had the wrong protagonist, that it wasn't really this guy's story. It's that guy's story. And that might seem like what a waste that was I, you know, writing that draft, but it wasn't a waste, I needed to do that, to see whose story it was. And then when I knew that I had to throw away some but not all of what I had written. Much of it was still exploitable usable inside the context with the with the other protagonists. But the point is, is that it is an evolving and mysterious process. And I see writers constantly outsmarting themselves. Just just, you know, it's not smart. It's dumb. I met my I'd mentioned earlier my dad, he had a very, very was a bass player. Stand up acoustic he was very, very successful in 15 years or 20 years in his early career at NBC on the arcturion Toscanini. And then 40 years the New York City Ballet, there's nobody that he didn't play with a record with him of any note note as the appropriate word in the last, you know, the mid the half century it's. And he made a very, very good living now what think about what he was doing, what was he actually doing? He was dragging horsehair. That's what the bow is made out of. It's a horse across sheep. Got sheep, the end trails of sheep. That's what they make bass strings out of. He was dragging horsehair across, across sheep got. Why are you doing that? Well, because it makes a sound. Well, I can believe in it just sound is it is yeah, it makes a sound that's so beautiful. that people will actually stand in the in line in the snow or in the heat to pay $100 or $300. You know, for the privilege of going into chamber to hear the noise that somebody makes. I mean, it sounds pretty crazy. But it's not any crazier than writing for the screen. I mean, When somebody comes up to you a stranger comes up to you and says, excuse me, excuse me, I writer. I had a dream. Last night, I have to tell you, I had this dream, I must tell you this dream come May I tell you this dream that I had. And let's say you're such a generous person, and so loving and so kind that you decide. All right, tell me, tell me your dream. Imagine if that person said to you, thank you very much. I'll tell you the dream. But first, there are two issues we have to address. One is, you have to be prepared to spend 100 it's gonna take me 100 minutes an hour and 40 minutes to tell you this dream. Whoa, wait a minute, I wasn't doing that. And what's the other requirement? The other requirement is I need $15 right now, or whatever else it got whatever the price is at a movie theater. Right? Let us figure that crank up the lithium on this guy's drip. He's mad, you know, I'm gonna stand here for an hour and 40 minutes and pay him for the privilege of and yet that that is just insanity. And yet it's what every writer is asking the audience to do asking scores 10s. In this world, hundreds of millions. I'll bet you a billion people on the planet have had some exposure to some aspect of the Star

Alex Ferrari 1:21:27

Wars more than that more than one and easily,

Richard Walter 1:21:31

you know, so it's, it's pretty crazy. I have a quick quick story about that, that's been on my mind lately, because I recently ran into the writer in the early 80s, long time ago now. The big item in in Hollywood was Beverly Hills Cop was very successful picture very good picture. And everyone is looking for Beverly Hills Cop now with my class, the main class at UCLA, I used to lecture to hundreds of students from time to time, one hour a week. But the main class that I taught every single quarter that I was there, we have 310 week quarters, instead of the more traditional two semesters, every academic so three times a year, I would have a 10 week seminar with eight writers around the table. And at the first class, everybody would come much more than eight would come over, you're trying to figure out who's gonna be in the class and everybody, I might get 35 people showing up. But everybody would quickly pitch. The basic notion about what the script they wanted to write. This was a feature length screenplay writing class. And the there were no assigned readings, no tests, just one paper and it was a professional quality feature length screenplay. So what's the script going to bake? And before we got started, I remember telling everybody that right now what everybody's looking for is a cop action. cop buddy action melodramas, like Beverly Hills Cop. That's what the agents looking for. That's what everybody's writing goes across town. That's what produces a seeking. Therefore, don't do that. It'll be one of 600 such scripts. I said, that's the smart thing to do is to do that. Don't do the smart thing. Do the stupid thing. Nobody I mentioned. Nobody is buying westerns that hasn't been a winner. Right? A Western. It'll be the only Western that's out there. So a student in the class did he wrote a Western, I could walk you through and I can't remember the names of my grandchildren. I can't remember where I parked my car. But I can walk you through this script that this writer wrote almost 40 years ago. That's how good it was. And it was a funny Western. Now I've mentioned to you that I went to film school with really famous people. I also mentioned to you that I went to before that I went to school in Binghamton, New York. My roommate in Binghamton. My roommate at Harper College is Andrew Bergman. And he lives in New York. I live here but we've maintained we're still very very close buddies. Andy Bergman is a very well known writer, director producer he really was was the force that originated Blazing Saddles. He has story by credit plus a shared written by with Mel Brooks and three other writers. One of them by the way, is Richard Pryor.

Alex Ferrari 1:24:24

Yeah, it was about to be in that

Richard Walter 1:24:26