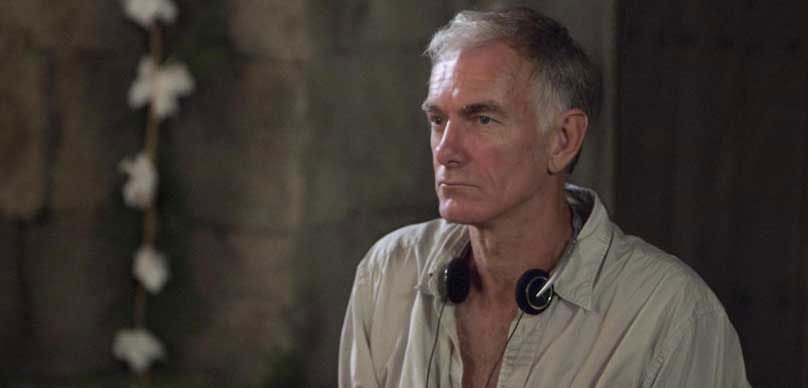

Today on the show we have screenwriter Brian Nelson.

Nelson holds degrees from Yale University and from UCLA. He worked as a drama instructor at Langley High School in McLean, Virginia in the early 1980s, where he taught Gilmore Girls actress Lauren Graham, Little Miss Sunshine screenwriter Michael Arndt, and UCLA screenwriting instructor Brian David Price.

Nelson’s numerous writing credits include episodes of the television series Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman, Gene Roddenberry’s Earth: Final Conflict, JAG and the Disney television series’ So Weird and In a Heartbeat as well as the feature film Hard Candy. He also wrote the play “Overlooked” and co-wrote the script for the vampire film 30 Days of Night, which was released in late 2007 and helmed by Hard Candy director David Slade.

Nelson wrote the script for the M. Night Shyamalan-produced thriller Devil. Nelson wrote episodes 3 and 8 of the Netflix original series Altered Carbon, as well as executive-producing the show.

His new project is Agent Stroker.

AGENT STOKER is a paranormal thriller – part Raymond Chandler, part Philip K. Dick, and all macabre all the time. AGENT STOKER is the love child of The Shadow and Black Mirror, it’s “The X-Files with a drinking problem.”

AGENT STOKER is the tale of a wounded man working for the Night Brigade, tracking data points that might just indicate coming apocalypse. AGENT STOKER is scripted supernatural fiction created by Chris Conner and Brian Nelson (both from Altered Carbon).

Brian and I had on heck on a fun time talking shop. Enjoy my conversation with Brian Nelson.

Right-click here to download the MP3

LINKS

- Agent Stoker Podcast

- Brian Nelson – IMDB

SPONSORS

- Bulletproof Script Coverage– Get Your Screenplay Read by Hollywood Professionals

- Audible– Get a Free Screenwriting Audiobook

Alex Ferrari 0:00

I like to welcome the show Brian Nelson. How're you doing? Brian?

Brian Nelson 0:14

So far so good.

Alex Ferrari 0:16

We have been talking for I don't know, 20,30,40 minutes before we even got started. So I have a good feeling about this conversation. I think we're gonna have a lively, a lively, you know, trip down the rabbit hole of screenwriting in the craft and a few other surprises, I'm sure. So before we get started, how did you get? First of all, why? And how did you get started in this business? Like, this is a ridiculous?

Brian Nelson 0:42

Why would anyone get started?

Alex Ferrari 0:44

This is this is an insane business. Like, you know, it's insane. How did you get started?

Brian Nelson 0:49

I had the fortune not to know how insane it would be before I am.

Alex Ferrari 0:53

Fair enough,

Brian Nelson 0:55

You know, long version or short version, which would you like,

Alex Ferrari 1:00

Whichever you'd like to whichever one? Whichever, whichever feel you feel like you like because we're gonna be here for a minute

Brian Nelson 1:06

I make my own grave.

Alex Ferrari 1:07

Right, exactly.

Brian Nelson 1:08

Right. All right. Um, for for various reasons that are part of the long version, I had this notion that, oh, maybe I'll try to like work a number of different jobs over my life. So I worked for a little while as a high school teacher and I worked for a little while as a theatre director. And then I'm thought, you know, I'm gonna move into writing. And of course, once I moved into writing, that means working in new jobs all the time. So I didn't have to actually continue that model. Because I was constantly as a writer, you were, you know, reinventing yourself all the time, and you are taking on new territory and responsibilities all the time. 10 years ago, I had to learn everything there was to learn about Florence and the Italian Renaissance for Da Vinci's demons. Little later, I had to learn everything there was to I read every word we still have written by Lee Harvey Oswald, because I was doing a deep dive into the Kennedy assassination for 1122 63. So so that is part of it was that I had this sort of sweet, idealistic notion of, oh, let's just live a life where you're constantly reinventing yourself. And then I stumbled upon this career where I'm, in fact, already constantly reinventing myself. So get Be careful what you wish for. You know, having said that, I mean, I've always on some level, you know, I was that kid in first grade, I was writing little episodic stories, like, wow, yeah, I know, I stumbled upon this one day. And I was like, I did this. But yes, here's like, in my little first grade handwriting, there's chapter five, where there's like a team have, like, sort of Mission Impossible type, operatives. And, and, and they all kind of happened to be my friends, but they all had code names. And I was x five, who was secretly the robot, which, what does that say about my like, self image, and we'll leave that for later. At any rate, so So I've always, you know, since since my earliest memories been, sometimes despite myself, I've been a storyteller and, and, and to get like, a little more thoughtful about it, you know, I think that on some level, that's our job as humans is to take a universe that seems without reason frequently and figure out the reasons make things make sense. You know, that's our gift as humans is to be able to interpret a possibly meaningless reality and ascribe meaning to it and make sense of our lives that way. So I figured out somehow within all that, how to actually make a living doing the thing that I think humans should be doing anyway, so, so far, so good.

Alex Ferrari 4:22

Yeah. And you're absolutely right. I think it's, it's, it's it for a writer, I think it is our responsibilities to to be able to give some sort of meaning to this insanity, that we are just our life and why we're here and what's going on and doing these deep dives, especially you know, going you know, doing research on your career. And you just mentioned a couple like the you know, the Renaissance and the the Kennedy assassination and there's those a couple of vampires in there and there's a devil in there as well. There's a few other things that you've you've really delved into a lot of things but as storytellers you're absolutely right. It is our job to kind of do that in an entertaining fashion because That's what we were doing around the campfire. You know, 1010 20,000 50,000 years ago, it's, you know, and stories I always tell people stories are they saved your life because if you didn't tell the story about the tiger who ate that guy around the corner, down by the river, if that story didn't get out, the tiger would still be eating people left and right.

Brian Nelson 5:22

Well put, and you know, I have a friend who told me once, like, I actually get into that whole campfire thing when I'm pitching a story to executives, like, I channel all of like the 1930s radio drama energy that I can. Yeah, a friend says, Yes, Brian, you have this, what he calls this, your dark campfire Mojo, where you're telling this story and you're making it clear that like, if people don't listen, something terrible might happen. So yeah, your your best, Orson Welles, your best Orson Welles. This is not the first time that that analogy is true.

Alex Ferrari 6:06

Now, you did a movie called Hard Candy in back in 2005. I remember when it came out. And it kind of it was very risque for that for its time. I remember, people were like, what? Like, they were really It caught? It really caught a lot of fire. How did you get from the How did you get from the script, to production, to Sundance and then and then you know, finally getting it distributed.

Brian Nelson 6:35

I mean, hardcat it was a tremendous experience. For me, I had been working as a writer for a little over 10 years where I'd done I've been in a writers room on a series, I'd written a miniseries written a mini series that did various freelance gigs. But also, I was like, trying to figure out how to, like, let things catch fire. And, and honestly, I had no idea that hard candy would be the thing that caught fire, but a producer named David Higgins had read a play of mine and head said, let's figure something out. And and he had a sort of clever idea. He was at the time a development executive himself who wanted to move into producing and his thought was I'm going to sort of see if I could come up with like, logline sentences for movies that could be made for like $15 and and find writers and develop them that way. And so we kicked the idea, various ideas around and one day he said, You know, there's this there's this story that I read about in Japan where these underage teenage girls would lure businessman up to their apartment with the promise of illicit dangerous sex, and then beat them up and rob them. And and we talked about like, it's really interesting, this dynamic of you start the story thinking, Oh, I should be afraid for this person. And then you realize, except maybe I should be afraid of them. And that was a felt like a juicy dynamic to consider and so we kept talking I shaped out really of a shockingly miniscule treatment I think it was like maybe four four and a half pages. And and David managed to say you know, I think we got something here but of course, I have no money but if you thought about specking it I bet we could sell it and it happened to be New Years and so I was like well, resolutions Fresh Start Sure. Let's give it see what happens if I give two or three days a week to just seeing what happens if I move forward with this story which at this point on the on the treatment was called Vendetta is very lame.

Alex Ferrari 9:17

Very beat very be very 80's be movie

Brian Nelson 9:20

Yeah. How to call it something. And fast forward on the title theme when we eventually were in production. We were like, well, we need a new title. I pitched her a while the idea of let's call it snip snip. Oh, and amazing. Always get some reaction but Hagen's Hagins to his credit, maybe not the reaction a

Alex Ferrari 9:52

Little too little too far.

Brian Nelson 9:54

So so he said, You know, there's that there's that movie where like the cheerleaders robbed the bank where it's called Sugar and spice. And maybe there's something in that vein where we talk about the like, bad dynamic. And so, along those terms, I pitched hard candy and as the title and that's what it became. So I've written the script, the script wrote remarkably fast. I mean, I, it just felt like I'm onto something here, it was one of those situations where like, you know, you, you set a certain quota for yourself of how many pages you want to try to draft a day. Sure, routinely, I was like, exceeding my quota and like, hitting dinnertime and going, I could keep going, I'd maybe I should stop now, while I still know what the next lines will be. I mean, it was just, it felt very fluid. I was at the right point, I think in my life and career to like, channel a lot of different influences. And it came also partly out of my theater experience. I had trained as a director in theater, Hagen's his plan B was, if we, if we never get any money to make this, then you know, Brian, you know, actors, we could just, you know, max out our credit cards and rent a digital video camera, and shoot it in my house. And so while I was writing, I was actually had in the back of my mind, right things that can shoot in David's house. You know, I was sort of choreographing it. I was writing it sure, you know, like a stage director thinking, Alright, now we should move to the kitchen, or when in fact, one day I got a ladder, and I walked up on the roof of David's house, you know, to see what that would feel like. David lived in a house all that also at that time that had a little interior rock garden with that, that we were like, there could be a safe under there, and so forth. So So I wrote it in a way for production, which I think was smart, something that helped. We sent this script around, we got a lot of great response. We got we got people who were like, people from studios were like, This is so great. Don't send it to us. Because we'll only screw it up. You know,

Alex Ferrari 12:26

That's just what you want to hear. Just what you want to hear

Brian Nelson 12:29

Fascinating response. And I mean, on some level, they weren't wrong, that they were like, you know, they they were basically saying, no, if you, if you do it here, then like you'll the development process will make will bleed everything special out of it. And it will turn out to be not a movie, where you know, this, this young kid executes this diabolical revenge, but she'll turn out to be Holly Hunter pretending to be a young kid or, you know,

Alex Ferrari 13:00

But isn't. But isn't it amazing, though Hollywood has I've never, I've never found another industry or another place where Hollywood, other than Hollywood, that they give you the nicest efuse I've ever heard. I mean, it's it's artistic. It's art. And that was that is I agree with you, although in this case, I prefer not to think of it as it No, it was, it was a little bit of it

Brian Nelson 13:23

Like wise, you know? Sure, counsel. So we started looking into how to how to make this independently. And Higgins thought, you know, if we find a director ourselves that we like, then we could present ourselves as a package. And frankly, a great aspect of this as well was that then the directors relationship would be with us. Because it turns out that you're your biggest loyalty is is often to the people that you saw as bringing you into the project. And so having that bond with a with a director that way was was tremendous for us. So we looked at reels of various people. And, you know, one of 17 Incredibly lucky things that happened on this project was we ran across the work of David Slade, who had been directing commercials and music videos, but had not done a feature was looking to do his first feature. And you know, we'd like very quickly realized, Oh, my God, here's a here's someone who could, as you see in hard candy, he could take a teenager looking through a file cabinet and make it look like The Bourne Identity.

Alex Ferrari 14:43

That's what commercials and music video directors have. They have that eye

Brian Nelson 14:47

He knows he knows how to shoot the hell out of something. And so we became this package. I will refer to them by their last names a lot since they're both David and but we became this package of me and Higgins at Slade And we looked to various indie funders. There was one group that actually gave us offered us twice the money we made it for. But their deal was, but you'll have to, like make it with our people. And Slade had very strong feelings about know if I'm going to make this for a price, it has to be my team that I know. Right? And I already have shorthand with that I can work with instantly. And so we were funded by Vulcan production productions, which was Paul Allen's company. And and they basically wrote us a check for a million dollars, which was a lot and not much at all. And we we hired an ingenious line producer whose job was to lie to us and tell us there was not much money left. Right. And, you know, we kept coming at him, he would eventually say, Well, I did squirrel away some money. And

Alex Ferrari 16:11

Yes, I love I love like producers who do that they're like, Well, you know, I I hit a little bit of money and put in design, so you can pull that out there. Oh, and props. I threw a couple extra grand over there. Oh, it's the best.

Brian Nelson 16:23

And, and so I'm gonna try to angle my camera here. Yes, yes. If you could see it,

Alex Ferrari 16:32

Oh, it's an amazing poster. That's an amazing poster. Yes,

Brian Nelson 16:35

That is this kind of collector's item. This is the poster that we made ourselves to take to Sundance

Alex Ferrari 16:45

Amazing, amazing design amazing design.

Brian Nelson 16:48

You know, equally amazing was the Lions Gate design when Lions Gate eventually picked us up?

Alex Ferrari 16:55

Oh, yeah,

Brian Nelson 16:56

That design of Haley in the hoodie, standing of that giant bear trap. Oh, unbelievable design. And I have that right and elsewhere. But this particular poster is always special to me, because it was seen only by, you know, 190 people at Sundance.

Alex Ferrari 17:14

So I'll tell you what, in 2005, we did you guys go into the it was the Sundance 2005. Sundance, right? Yes. That was my first year at Sundance. And I remember walking, and I was walking, I was walking Main Street. And I remember seeing the poster. And I remember hearing about an A here and we were there promoting our short film. And it was just like, Man, that's a great idea. And I just like in the in the marketing for that looks really cool. And it was just, you know, for people, Sundance was a whole lot different in 2005 than it is today. It's just a whole other. It hasn't turned into what it is today. And but I do remember oh five, and I remember walking the streets. And I remember seeing the poster and I remember hearing about that movie. So yeah,

Brian Nelson 17:57

It felt I will say it felt like a lot today a lot lot in 2005 Even I mean, it was it was that the place was jammed. And, you know, Sundance is is also I will take a moment to say, you know, wonderful in many ways and helped launch as and at the same time. Boy, they are focused on directors. So like, you know, the artists so much on the writer, not so much the writer. No, no, the artistic director introduced the film as written and directed by David Slade and David had to say I actually. And Sundance had not made a badge for me.

Alex Ferrari 18:38

Oh,

Brian Nelson 18:41

I tell that not to shame send it well, no, a little bit, just a little bit. But actually, not having a badge turned out to be great. Because they were like, well, we have a badge, but the name of your film. So I walked around town all week. And my dad said I was hard candy, and take that the wrong way. But I'd be on a bus and people would see my badge and they'd go, Oh, my God, I love that film. And, you know, whereas had I been wearing a badge that said, Brian Nelson, I just, you know, I wouldn't have any nobody would have talked to me, but I actually was wearing my own PR. And really that turned out to be honest. You know, if I'm at Sundance again, I probably want to do the same strategy and not have a badge but just have a badge with the name of my film because that was magic.

Alex Ferrari 19:43

Oh my god, that must have been amazing experience. And then it goes on to to do you know, well, it got picked up and it does well it gets critically acclaimed. So now how does the town treat you? Because you've been around you've been around for a few years. You're not you know, you didn't just show up with Your first spec script you've been writing.

Brian Nelson 20:03

It's interesting, because, you know, I got about three years later, my previous agent left the business and I signed with new agents. And when I'd see their resume that they'd send out on me, it began with hard candy. And I was like, Oh, that's interesting. For you guys. I didn't really exist before that. Right? That's fine. But um, you know, the fun thing about going on meetings in the wake of Hard Candy was that people read it. And they tell me all their experiences of reading it. They'd say, it was like Sunday at 1130 at night, and I was tired. I thought, I'll burn off one more script. This looks fun. It has candy in the name. And then I'm like, 20 pages in and I'm like, What am I reading at this hour of the night? Why am I all alone? And not very dressed? I should put on more clothes. So people loved telling me those stories. Oh, that's awesome. But also, I'd walk in and people would meet what you're seeing now people would meet a guy whose looks and sounds like me. Right! And they'd go. You're not who I saw.

Alex Ferrari 21:34

What did they? What did they think

Brian Nelson 21:36

Hard candy so they expected Marilyn Manson.

Alex Ferrari 21:39

I was about to say, like, with some emo kid to walk it

Brian Nelson 21:43

And I Yeah, exactly. And, and, you know, so I walk in and I mentioned I'm amusing and not right, you know, come in with a kind of a light touch and I'm easy to talk to, and I'm not like glaring at them. Like why you think you have the right to exist? No, no. So that was but maybe that was that was a surprising like comforting to people that oh, we wait to be scared of this guy.

Alex Ferrari 22:17

Now, so after you made your rounds in town, you and David Slade worked on another project shortly thereafter. A little vampire film independent vampire film that we call 30 Days of Night, which is a fantastic I mean, I love love, love that movie. And I love the shot. I love the way it was written. How did you approach adapting? Uh, this was a graphic novel, if I'm not mistaken. right it was .

Brian Nelson 22:44

It was a graphic novel, graphic novel created by the amazing Steve Niles. Yeah. With with art by the equally stunning Ben temple Smith. Yeah. And you know, it had been a sensation in comics. I'm one of those guys who you know, knows way too much about comics for someone my age, you know, here's this wall you see behind me with like Shakespeare and pincher, but literally on the other side of this wall comics are 29,000, Marvel and DC comic books. And so

Alex Ferrari 23:20

Well, we can get we can geek out then

Brian Nelson 23:24

Fair warning anyway, So So I, you know, I certainly knew of the project it had been through. It had been through several writers and the studio had reached a point where they'd said, we're not sure what to do with this, maybe we hire a director, and then the director sort of supervises a writer. And yet, this is Studio thinking for you, then they were like, but maybe we shouldn't hire the writer that the director wanted. Because then the writer won't listen to us. They'll only listen to the director which you know, having heard my you know, thesis about who hires you into your loyalty. I mean, that certainly makes sense. So therefore, I even though Slade wanted to bring me in on this, I still actually had to, like enter a derby for this. I was one of three riders pitching it I have never pitched two more people at once. 11 people included on the pitch including two on the phone, you know, from from the studio and two production companies and the publisher of the graphic novel. And so, so it was a lot but somehow, luckily, I won through and was tremendous fun to write. I can imagine and and what I what I look, Steve Niles had this brilliant premise for his story. So Like, the first, the first 20 pages, like, we're already home, and he had a brilliant ending. The challenge of various writers along the way was that, you know, there was there was not there was not much in the way of character arc yet or a second act. And so that's a lot of what I brought brought to that. But it was an interesting case, because also, you know, Josh Hartnett had been cast and won as part of his deal the right to like consultant script and, and, you know, we were like, holding our breath about, oh, what's, what's this actor gonna say? But Josh brought interesting ideas to it. Josh said, this is a small thing, for example, it's hardly like, when people list the the things they love about 30 Days of Night, nobody says, oh, and his inhaler. But actually, you know, Josh was like, I want to be an ordinary guy. I don't want to be a secret superhero. And so, so like, Could we just, you know, give me like, a little asthma issue and silver so that, like, when I run around the corner, we're not going to do the scene of like, must get inhaler, right. Yeah. You know, it would be great. If I just had to take a moment every once in a while to just puff, you know, I just need a little help. I'm human. I'm an ordinary god. That was an example of something that's actually suggestion suggested that I thought would be great. Josh also suggested, what if? What if I have like, a little brother, because the little brother was not in the graphic novel. And and Josh suggested, you know, if I had a little brother, then that would be go to like the themes of family in the story. And when I thought about that, I thought, Oh, this would be great. Because if his brother is like, 1719, he is like, Josh is the sheriff. Josh plays Evan Evans good at his job. You know, so, so Evan didn't have technical challenges of can I really do this, you know, he, he steps up to the moment, but his little brother is his little brother. And so like, having to watch his little brother have this coming of age where it's like, Oh, my God, I just killed a vampire. Maybe I need to go throw up. Now, you know, that was a tremendous dynamic to have. And, and, you know, watching watching that character have that little arc, again, not something that a lot of people when they, when they list things about the movie, they nobody ever says to me, oh, have a little brother. But it was part of the texture of that, right? It actually made it so human and so rich, and that to me, in everything I write, I'm looking for that humanity. I'm, I'm, I will often say to people that regardless of what genre I'm writing, I write about people who find themselves someplace where the rules have changed. And now suddenly, it's up to them to decide, whoa, what are the new rules is going to be? And when they make those decisions about what's what's going to be right and wrong in this new paradigm? What did they discover about themselves, that maybe they didn't want to know? So that's what I love is taking people putting them in a gray area where they have to make those hard choices, look in the mirror and go, Wow, that's who I am, what the hell do I do with that? And that is hard candy. And that is 30 Days of Night, and that is altered carbon, and that is Agent Stoker. And it's and so you know, even though I write in various genres, and have have, you know, a sort of complicated resume, that's my sort of unified field theory of what I write,

Alex Ferrari 29:21

And that's a that's a really great point of view. Because I mean, I've never heard it illustrated that way before. Because, you know, obviously, the the ordinary world and you go into the, you know, the New World, and that's the concept of that, but putting them in a place where the rules of their environment have changed, like in devil or, or like in 30 days a night where you were, I mean, obviously, you know, you've got vampires in the sun's never coming. Like that's a great such a such a wonderful concept for a vampire movie. It's like, if you're going to do a vampire movie, it's such a great thing but that and then also I just love the idea of the vulnerability of Josh's character, not only because of the inhaler, which is a brilliant mood, brilliant, brilliant idea. But having the brother and having to watch his brothers back as well gives him another vulnerability. He's like, he's not only dealing with asthma, he's not only dealing with a town full of vampires, he also got to watch his little brothers back and take care of them as opposed to so it's just all those little, those little parts of the tapestry add so much to the character. You're absolutely right. But I love that idea of the throwing them in a gray area where the rules have changed and see what they do when you apply these new, this new paradigm to them.

Brian Nelson 30:39

I mean, not that, you know, my feeling is sometimes the gray area happens for various reasons. Sometimes it's thrusting upon you, without your being prepared for it or having asked for it other times, you semi wittingly or unwittingly created it because you were pursuing something and then guess what it puts you now in this new territory? Right? You know, you to be careful what you ask for kind of situation, like so people, people can find themselves in the new paradigm for different reasons. But, you know, on some level, I'll even say that that's, you know, that is me as a screenwriter, that I was a guy who was like teaching school and directing theater, and then I entered screenwriting. It's like, whoa, the rules are different here. I have a lot to learn. Even though I thought I was pretty smart, man, there's still a lot to learn. So

Alex Ferrari 31:34

And the game change, and the game changes almost weekly.

Brian Nelson 31:39

Always asking myself, am I capable of what am I capable of a while I and and surprised? I didn't know I could write that. But I guess I just did. So yes, exactly. And it's fine.

Alex Ferrari 31:54

Let me ask you. So I always love asking writers this, about the flow about being able to tap into their creative. Well, I believe that we all have a creative Well, I think Spielberg said it best is like ideas float in the universe. And they will come to you. And if you don't do something with that idea, it will go to somebody else. And that's why he's like, Oh, I had that idea. But I didn't do anything with it. And like six months later, oh, it's in production. Damn it. I have a great print store, if you want to hear Prince story about her. So Prince, Prince, I was writing as

Brian Nelson 32:29

Another Nelson. So, you know, I'm automatically in sympathy.

Alex Ferrari 32:33

So prince, the the late great prince called up his, you know, he has like 1000 songs. And yeah, he's got a new album up into the year 3000. So a new album every year up into the year 3000, we will continue to have prints. So he would just call up his his backup singers and his musicians at whatever time whenever he got struck with with inspiration. And one night he calls up his his, uh, his back of one of the backup singers and says, Hey, what are you doing? It goes, I'm sleeping Prince, it's three o'clock in the morning. Like, I need you to come down to the to the recording. So we're gonna record it. What can you just wait, like, for four hours? Like, no, I've got to get it now. And I got to get it recorded now. Because if I don't Michael Jackson's gonna get it. And that was such a amazing, like little peek into his creative process. He really understood when he had an idea or an idea came to him. If I don't act on it, it's gonna, I'm gonna lose it. So I always like asking writers What do you do to get into the creative flow and how to tap into that well, of creativity that is that is yours that you get that that Muse if you will, to tap into that?

Brian Nelson 33:46

I mean, that's a very interesting question. Because like, I'm, I want to answer it in at least a couple of different ways. And this may be my, like, Libra quality, you know, my wife's complaint about me? Is that the answer to every question that she asks me as well, yes, and no. You know, and so there's a part of me that wants to say, actually, no, you don't have a choice. There's nothing I do. I it does me, you know, that, like, I, I will just have to come downstairs at 1230 at night because I can't sleep and I know, I have to write it down so that I can sleep. You know, because otherwise, you know, the ideas just gonna keep kind of going, hey, hey, anything about me? You know, so, so there's that, you know, having said that, I will also say obviously there are you know, I mean, like I you know, spent a lot of time trying to figure out how to work Pandora to find a way to curate for myself a collection of music. That would be only so interesting. to keep my mind occupied a little, not so interesting to distract me.

Alex Ferrari 35:07

So find balance.

Brian Nelson 35:09

But interesting enough that when my mind goes on, do you want to think about something else? I've already fed it. This, this minimally interesting music. Okay? Yeah, no, yeah, I was too if I were writing in silence, I would go and, and, you know, go do something else. You know so so knowing you know, knowing something about how your brain works and what your capacity is, uh, you know, I I'll arrange various treats for myself, you know. I'm a big believer in you know, the, the animal moths book Bird by Bird and then feeling like, you know, you don't have to do it all at once, break it down into little chunks, Bird by Bird. And lo and behold, you write about enough birds and you got an aviary. I don't think that's quite the way she put it. But brick

Alex Ferrari 36:05

Brick by Brick a piece of the elephant a bite of the elephant at the time.

Brian Nelson 36:08

Yeah, exactly. Exactly. So um, so those are, you know, that I certainly have my, my schemes. Having said that, once I had two kids, I also got really good at writing whenever there was the time, because, oh, yeah, I used to be a guy who like, and still am somewhat a guy who like I love writing, you know, in the middle of the night, when the house is all asleep, and I have everything to myself and no distractions it's over. But being a parent, man, I learned to write in like, the little time from 1005 to 10:23am, or whatever, you know, that, that, you know, being a parent of young kids meant you were signing on to a life of none of your plans going like you thought. And so, so as a sort of evolutionary survival strategy, I acquired the ability to write when I got the shot.

Alex Ferrari 37:14

And it was very much like Stephen King, you know, when he was writing carry on a typewriter on his lap, in the laundry room, you know, and he was just like, as he's doing laundry, he's just typing away on carry his first novel, and you just do what you got to do. And if it's five minutes, it's five minutes, it's it's five hours, it's five hours, it's whatever you can, but you just got, I think the key is also just writing, just just write in, all the bad stuff is gonna flow out

Brian Nelson 37:37

Absolutely. And, and, you know, the world is full of people who want to have written,

Alex Ferrari 37:46

Oh, they want the glory, but they don't want to do the work.

Brian Nelson 37:49

Maybe not even necessarily glory, but they want that feeling of I have written them. So I am, you know, I'm able to, like, look back on it, and so forth. But you what, what one needs to acquire is the pleasure and the joy of, of writing, as opposed to having written and if you don't have that I enjoy is actually writing. Again, it's got to become an insufferable slog, and you're going to very quickly find a way to do something else. That might also tangentially involved stuff you forced yourself to write, but, but the actual process of writing is, I mean, again, I was I was doing it when I was six years old, without even knowing why I was doing it, you know, right. It's unfortunate in that way that it's, you know, I'm not a musician, I would love to be, oh, same here. But, you know, I have a musical instrument here that my wife gave me that I took some lessons on. But as much as I love the ideas of musician, I don't have music. I don't actually yet, maybe that'll change. Maybe I can tell myself, but I don't yet find pleasure in the actual like, playing in the actual making of the music, whereas I do and always have found pleasure in stringing a mess of words together and seeing what happens and and changing the words that go wait, maybe maybe, in fact, a shorter sentence here and so forth, you know, and that that is is feels like home.

Alex Ferrari 39:34

Yeah, and that's another thing that you know, as creators, we a lot of times want to want to be at the end of the road and don't enjoy the journey and it's always about the like the end the finished screenplay, or the finished movie and but the painful for many people, it's painful to get to that point. That won't you can't sustain a career that way you need to enjoy this process. You need to enjoy any process you're doing because As the bulk of the time you're on this planet is in the journey, it is not in the, it is not the one that is not the one that you win the Oscar. It's the 20 years that you were working towards that process to get to the Oscar, if that's a goal of yours, or whatever, but it's that's it, those moments are so short. And you can live in them for a minute, and then you're done. And you're like, Okay, now what? You but

Brian Nelson 40:22

I mean, I feel secure, saying, Alex, I'm not gonna win an oscar. That's alright.

Alex Ferrari 40:29

You're right, me, you

Brian Nelson 40:31

Kind of work that gets considered for that. And that is perfectly fine. Because I love the work that I'm doing. Right! If it ended up that way, am I gonna turn it down?

Alex Ferrari 40:41

No, no, no, I don't want

Brian Nelson 40:45

No, I'll take it. But

Alex Ferrari 40:47

Give it to Eric Roth again. Don't give it to me. No, I understand. No, I understand completely. And I think you and I are both in that same category. So it's not bad. It's not bad. It's not like most of us are in that category. Now, I have to ask you, you got to work with arguably one of the better, one of the best voices in his generation, I think for as a writer is M Night. And, you know, coming out with sixth sense. And, for better or worse, always having to live up to success with the rest of his career. But he's a brilliant writer, and I'm such an admirer of his because he had reinvented himself a few times. Because there were moments in his career where Hollywood just wrote him off. He's like, up, that's the end of that. But he just kept his head down and kept putting out great work. And then he's had this, this resurgence in the last, you know, five, eight years of just putting out great work, what was it like working? And how did you get involved with nit for devil,

Brian Nelson 41:53

You know, time and again, I find myself saying, Well, I was really lucky. And you know, of course, you know, luck is partly that I kept my head down and kept working. And so you know, the more work you do, the more luck finds you. But nonetheless, I was approached about devil by night. My agent called and said, I'm not channeling wants to meet with you and okay.

Alex Ferrari 42:27

And you're like, who does? Who does? Who does? This is a joke?

Brian Nelson 42:30

Well, well, so he says he's the what I'm told is he's he's in a hotel in town. So go to the hotel, and he'll come down and meet you and was oh, so friendly. It's sweet. It was like, amazing, because I remember being in the lobby of this hotel. And they say, All right, well, here, you can call up to his room. And so I'm on this, you know, the hotel phone saying, Hi, this is Brian Nelson. I was told to call this number and, and I hear this voice saying, Hey, buddy, it's night. And like, alright, we're off to the races. So night hat, the way that he framed it to me was he said, You know, I, I've had two or three ideas that feel like little films that could be fun, but maybe they're maybe their ideas that would suffer under the weight of written, produced and directed by Night Shyamalan there, there. There's smaller films, and I've made this deal with this company, media rights capital that I will produce and supervise writers and directors in this. And we'll we'll make these three films, and I don't I, I'm not sure they all got made. But I was the first out of the box. And he gave me like a 678 page treatment for for what became devil and said, Is this is this something that you would want to write? And I told you earlier about my sort of what I frankly call my mission statement, you know, what, like, is it about a character who like finds themselves? And, and I frankly, I use that as a rubric. So I mean, look, of course, there was a part of me it was like, well, if I'm my channel and asked you do you want to write something? Of course you say yes. But also, frankly, no, I also had to ask myself, does it fit the mission statement? Because I have found in my life that like, if I try to write things that are not in that zone that I've identified as my zone, right, they're not going to go well. Right? But devil totally fit that. And so I was happy to sign up and And I did a number of drafts, I worked a lot in close consultation with the dowels, John Eric Dowdle who directed it and his producer brother Drew, we, we hung out quite a bit talked about the story from different perspectives. And so it was it was a very effective collaboration and a film that, you know, again, I'm, I'm very lucky that people you know, come up to me all the time and go oh my god, I just literally a guy I know. Last month said to me, I was watching this film and I didn't know you wrote it. And at the end of the credits, I was like, ways that Brian Nelson that I know. You know, frankly, it might not be because they're turned out to be a couple 36 Brian Nelson's on IMDb, of which I am Roman numeral two. High up there has because I've been around so damn long. You know I joined IMDb I started logging on to IMDb when it was run by a little college in like Louisiana. And there were two. And I was I was on IMDb too, because my last name is between M and Z. You know, that's how primitive it was in those days. Wow. But there's a lot of Brian houses in the world as it turns out, but I wrote Devil and that my friend was like, I didn't even know. And it still continues to haunt people's nightmares. And, and so

Alex Ferrari 46:43

It's, it's it was terrifying. I remember when it came out, I saw it was terrifying. And and I remember people just talking about it like did you see devil? Do you see that? Like it was just there was a little thing in the air about it. I

Brian Nelson 46:57

I have a very good friend who's a very accomplished director. And maybe I won't mention her name because I'm going to talk about this phobia of hers. But like she called me up and said, I'm so happy for you, but I can't see it because I just got through months of therapy to be able to enter elevators.

Alex Ferrari 47:19

Oh my god, so you've tear up? Yeah, of course, she would never be able to ever, never ever be able to get into an elevator again. Now, you know, working with them night is is Was there something? Was there a lesson or something that you saw in his working in his writing process, and his storytelling process that you kind of nugget that you pulled away from working with him?

Brian Nelson 47:40

I mean, you know, night is a tremendously inspirational figure in terms of like, never be afraid to do the next pass. There's always more to do. You know, we You talked a moment ago about people saying, well, they want to, like, have that finished screenplay. But you know, there is also a saying that, like, no work of art is ever finished, it is only abandoned. And, you know, and and, you know, I remember hanging with knight in his study, and he's got all the drafts of everything in his study, there on that shelf are like 19 drafts of signs there on that shelf are 12 drafts of late in the water or whatever it is and so forth. And and, you know, he, he is a demon for work. And that to me, I always find very inspirational is that, because I believe that at you know, I've talked quite a bit already about you know, that you have to find a pleasure in writing. And that means, of course, absolutely the pleasure in rewriting. And you know, and I remember night saying what's, you know, sometimes sometimes it's interesting, Brian, you'll do a draft and it's got problems and then the next draft has like moved it forward so much and and, and then maybe the next draft will have more problems, but then the next draft moves it again. And it's yeah, you you go through, you know, you go through a sine wave sometimes of of finding things in a story and he was a great companion in those terms.

Alex Ferrari 49:21

Now, you you've written some very suspenseful stuff in your career. What, how can you create suspense in a scene? what's some advice you can give writers on how to create suspense within a scene? Not a whole movie, but just within the scene.

Brian Nelson 49:39

So years ago, I was working with producers at BBC Worldwide. And they asked me to write a piece. I wrote a pilot for them that was about the Georgian era in England. And I said had, I don't want to look a gift horse in the mouth, but I'm not like that person who would normally come to about this. I'm like, the vampire guy, right? And, and they said, we don't think of you as the vampire guy. And they said something that I was like, one of the nicest things people have ever said about my writing. Because they, they said, you know, we look at heart candy, and we look at devil and we think no, Brian writes about two or three people who go into a room have a conversation. And at the end of their conversation, both their lives are changed. And, like, if that is what ends up is my epitaph.

Alex Ferrari 50:46

That's a great epithet cheese, you know.

Brian Nelson 50:48

And this is part of my training as a stage director is, if something is going to be in front of our eyes, then it needs to earn its key, and it earns its key by in any given scene, something must change. And that change happens as a result of. And I'm going to sound extremely academic here, but each per each character's active intention, what is each person trying to do to affect the other person and create a change in that other person, and then one of them wins, or maybe they both win, maybe they both come to, you know, a realization, or, or their conflict creates a new problem or possibility. But But every time if a character is going to earn their weight in a scene, then they need to show up with a goal and intention, something that they want in that scene, and a plan to get it. And then they change. If that is true of the whole script. The entire script is how did this person change as a result of the choices and plans that they made? And what sacrifices did they have to make. But it's true of any five page scene as well is when characters leave that scene. If that scene was just about, oh, we want to establish the house or we want to show how sexy these people are, or whatever it is, then to me, it's not earning its caveat that that something must the status quo must have evolved by the end of that scene. And the other going to your suspense question. Ideally, I think every scene ends with a question that that that if a scene doesn't have a what will happen next at the end of it, then maybe you need to keep working on that scene. The only scene that shouldn't have a what will happen next is the final scene and even then, you're usually happier if you still have that movie ends and you're still wandering away. Isn't there more what next? Right and so so I'm, I'm obsessed with, with story questions, what do people want and what will happen next?

Alex Ferrari 53:32

Now in your, in your travels, you you've written in a few writers rooms. Couple, the one thing that in schools and in in academia and just general that's not talked about a whole lot at the politics of the writers room. Are there any tips you can give young writers who if they're lucky enough to get in a writers room? A couple landmines they should look out for as far as political, the politics of room and obviously that changes per room and per showrunner, but generally,

Brian Nelson 54:04

I do well in writers rooms, I think because I'm there to be part of a team and they're to engage and I'm not precious about my words, because I know everything's being rewritten all the time. You know, and so, so I really enjoy rooms because I think partly because of my theatrical background that I you know, grew up working in stages where, you know, even if you're a one man show, you're still gonna need a stage manager and a lighting designer and writer and so, you know, and so, so I I really feel at home in collaborative art forms. If I wanted to do it all myself. I would be a novelist or a poet. Right? But I don't actually Want to do it all myself? I want to work with partners and people who will, people whom I can challenge people who will challenge me people who we can all make each other better. The more voices This is partly an exciting time in television, because we are bringing out more voices than we ever have in maybe even the history of culture. And, and so that's, that's a thrilling thing. So, so I, you know, if, frankly, it sounds a little simple, but my my just advice would be, first of all, just be open, be open minded and be willing to contribute. And don't be, don't be precious about oh, this is my idea, or, or what, or this is how I wanted to say it, because it's all gonna change seven more times. Anyway, right? Later. But, but the more that you engage in a spirit of not about oh, what you said versus what I said, and more about, what is the story? What what did these characters want? As long as you're talking about the stories and characters, then you're getting it out of the realm of ego and into the realm of craft. And that's what I think makes a successful room.

Alex Ferrari 56:26

Now, I'm going to ask you a few questions. I asked all my guests. What was what was the biggest fear you had to overcome to write the first screenplay, your first screenplay? Because I'm assuming you didn't just go in all guns blaring. I'm assuming there was some, Hey, can I do this? Or you know, things like that?

Brian Nelson 56:46

Ah, you know, I've been around a long time. So now you're asking me to cast my mind back? decades? decades. I mean, I, you know, I, it's, it sounds very simple, but probably the biggest fear I had was, am I wasting my time? Is this something that I could be good at? Right? Um, you know, and I, I gave myself a certain, like, clock by which I needed to see some signs of success, or I would decide, you know, don't knock on a door that nobody's out. On the other side. You know, and, and luckily for me, someone knocked pretty early before that, because I didn't give myself frankly, the longest timeframe for that. So

Alex Ferrari 57:45

What was the timeframe? By the way? Was it like a couple years two three years?

Brian Nelson 57:48

Oh, no, no, no, my charter the math.

Alex Ferrari 57:50

Oh, really? Now, what was your timeframe?

Brian Nelson 57:54

I, I had written I mean, effectively, maybe it to turn out to be a couple years, but I didn't think of it that way. I, I was, I was directing plays, I was making money on the side writing script coverage. I was also working a day job while my wife was in grad school. So I didn't have a ton of time. I wrote two episodic specs, samples, like back in those days, you wrote samples of shows that were on the air. Sure, sure. I sent them to agents, people were like, this is nice, thank you. Send them what status? What else? Everybody else here? Right? I'm like, Okay, I got to do some more. I wrote a spec movie the week setting reaction. And so then I was like, Well, I'm going to write a screenplay. And I'm going to write the best damn screenplay. I can imagine writing and I'm not going to think about whether it's commercial or whatever I should you know, I you know, I people were like saying, but could you write under siege to Shouldn't you think of that and you know, and and I was so so no, I'm gonna write the best possible thing I can write and if it goes somewhere then it goes somewhere and if it doesn't, that will be that then that then that will be that and I will focus on where people seem to be interested in my so you ask luckily for me, that script out my even hardly trying God response I because through theater, I had a friend who worked in script development, his his day job at night, he was working in theater like me, but his day job was he was he was worked in mo W's for for a studio. And I asked to just as a pal, could you give me notes on this to try To help me get an agent, you know, I'm not submitting it to you. Right Man. Yeah, just please. I will benefit of your wisdom, any notes you could give me. And then timidly like two or three weeks later, I poked my head in his door. And I was like, I don't mind. Yeah. Yeah. And, and Eddie said, yeah, no, no, I have no notes. I think it's great. I think we should buy it. Well, they didn't buy it. But He then got it to a producer who actually optioned it and got me an agent out of it. And suddenly I was like, Well, I guess I can do this. And I guess all. So persevere. So so.

Alex Ferrari 1:00:47

So the advice you're giving screenwriters is give yourself 12 months, write one screenplay. That's it. And if it doesn't work out, then go do something else. That's basically what you're saying.

Brian Nelson 1:01:01

All I could do is report my journey. Of course, no, no, of course, I have friends who have worked in this for years. And it is their dream to write movies. I as I think I told you way along was like, there could be a lot of things I do, maybe I'll be a sociologist, you know, I need that was actually something I considered for a bit, you know, so so, you know, I, I love telling stories, but I was also prepared for this not to work out. And, and it's awesome. So, again, lucky for me, because it did.

Alex Ferrari 1:01:45

But the thing is, but the thing is, you've spoken about luck, a bunch in this conversation. But the thing is that you, you created your luck, because you actually did the work. It's not like someone knocked on your door like, Hey, man, do you got any ideas? Hey, I'll pay you to write a script. Now. That's not the way it was you you put in the labor? And then look happened?

Brian Nelson 1:02:05

Sure. So now I will tell you, I've told you my unified field theory of what I write now, I'll tell you my Unified Field Theory of careers. Okay, so these back in those days, I was watching and going, Why are those people who are so brilliant, but they are not. They are not getting their careers are not moving forward. I mean, while some other people who frankly, I don't think are so brilliant, but they are working like oh, what's that about? And so I devised this theory where you have to imagine a triangle. And each of the points of this triangle is a different aspect that might help you get a career. But the secret is, you don't need all three. Your career is a line that connects the two, you only need two of them to have a career. So the three points are talent, perseverance, and luck. So you might have no talent. But if you persevere, and you are lucky, you will have a career. But you might have no perseverance, like writing one script. Wow. But yes, but if you have talent, and you are lucky, you will have a career. And then we all know people that have no luck at all, but they have talent, and they never

Alex Ferrari 1:03:44

Rightand they build something out for themselves.

Brian Nelson 1:03:47

And I constructed this theory at about the same time that I was writing that script so maybe I've always been trying to talk myself into persevering now, you know, that's not fair.

Alex Ferrari 1:04:00

No, that's not fair. Because you you've done a lot sir.

Brian Nelson 1:04:03

I work a lot. Yes, you do. But but the corollary to this triangle is my talent is what it is I could improve I could look study craft I read other people's scripts all the time. I I like watching bad movies, because it's like, oh, what can I learn from this? How did this go awry? You know, but, but at the same time, to a certain extent your eye is your eye you got a little bit what you got through the the vagaries of fate and genetics or whatever else I don't know. Your Your talent is somewhat of a fixed quantity. Your luck, you have no control at all, but that's why it's called luck. So really the only thing you could control Is your perseverance? Absolutely. And so so that is my actual advice to people. Alex Ferrari is persevere,

Alex Ferrari 1:05:13

Or possibly even hustle.

Brian Nelson 1:05:18

Yeah, yeah, you might you might know it's true, because because look, that whole anecdote about that screenplay is on the other hand in the context of, but I was I've, I've been working, you know, since high school in the arts and I've been like, you're reacting directing. You play writing, we're honing out.

Alex Ferrari 1:05:41

You were honing your craft.

Brian Nelson 1:05:42

And well, I mean, yeah, I guess I don't ever think of it as honing my craft. That sounds so kind of,

Alex Ferrari 1:05:51

Well, no, but you I mean, but you were telling stories. You were working in the art. So you were you were gathering things left and right.

Brian Nelson 1:05:57

I'm, I'm, I'm pursuing the story. I, you know, I was I was in graduate school at UCLA. And there was a professor named Michael Gordon, who had this amazing career he had worked with a group theater. Then he directed the film of Cyrano de Bergerac. Okay, which one the Jose for? Yeah. And then he got blacklisted. didn't hardly work through the 50s. When he came back, he managed to direct again, but not Cyrano de Bergerac his comeback film was Hello, Taw with Rock Hudson and Doris Day, but he took that job and made the most of it. And continued working for years of years. And so he was a guy who just managed to build his career out of what is the story? What will people what will make people want to wonder what happens next? And I, I looked at the plays that I had directed, and the ones that had we had worked and the ones that have not worked? And I was like, Oh, the ones that work? Or what are the ones about story? The ones that made people wonder what would happen next, right? The ones that were just about a theme or an idea? Yeah, maybe there's people who can make pieces about theme or about spectacle, right? We're without story. There's people who do that.

Alex Ferrari 1:07:36

Oh, and I won't say their names into out loud. But yes, there's there's more pillar to them build careers upon

Brian Nelson 1:07:42

I would never harsh anyone else's jam. Absolutely. But what what makes my work work is story and character. And, and I, I I realized I could be intellectually tempted to work on a piece that's just about like, the fascination of language or whatever. But no, those pieces, those pieces are going to be only interesting to me. Fair enough. Fair enough, you know, and so that's, that's what I learned. And and so so maybe I'll revise my my, my screenwriting origin story to give myself a little more credit.

Alex Ferrari 1:08:24

You should you should, I think a little bit more credit. I mean, though, because you, it's not like you just like you were working fries, at a Burger King. And all of a sudden, like, I'm gonna give myself 12 months in one script to write and I've never haven't barely written anything in my life. That's not what you said, You've been working hard to get.

Brian Nelson 1:08:40

Now, it's totally fair. In fact, even even the day job actually was I got a job in a studio legal department, right. So I was in fact, watching the business of how you were being put together. I was like honing, Travolta get to fly his own plane to the sad why does that matter? Hmm. Interesting. Okay.

Alex Ferrari 1:09:04

So, um, that's a whole other episode. Just what you learned during that process time. If all the inside stuff of those those deals. I have two more questions for you one. What is the lesson that took you the longest to learn whether in the film industry or in life?

Brian Nelson 1:09:22

The lesson is make sure that Alex asks me in the second question about agent Stoker, which I'm dying to talk more about. Okay. Okay, now ask me that question again. That's all I could

Alex Ferrari 1:09:38

Well, tell me about yourself at first.

Brian Nelson 1:09:41

I did last year.

Alex Ferrari 1:09:46

I've heard this thing about HS dopa. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Brian Nelson 1:09:49

Um, so look, this is i This has been such a fascinating, fun journey for me. I met Chris Connor On earth through altered carbon, where he played Poe, our AI who believed he was Edgar Allan Poe. He crushed that role. Shortly into the pandemic shutdown. He was like, Hey, since nobody can like shoot anything. What if we like created a podcast? I have like this feeling that like, I keep thinking, Is there a way to do black mirror meets the old radio plays of the shadow? And I said to him, you know, if someone worked in a lab, and tried to figure out the phrase to fastest penetrate into my cerebral cortex, I don't think they could do better, like very relevant. Yeah, I write that. And so what we cooked up was this scripted supernatural podcast, call it a paranormal thriller. It is called agent Stoker. And it is we have various line log lines for it. One is of course, Black Mirror meets the shadow. Another is part Raymond Chandler, part Philip K, Dick, and all McCobb all the time. Oh, sounds amazing. Another logline for it is the X Files with a drinking problem.

Alex Ferrari 1:11:33

What a great image. That's amazing.

Brian Nelson 1:11:35

Ancient Stoker works for a covert organization called the knight brigade, that is tracking incidents that have no explanation. But maybe the explanation if we can all hook them up is that the end of the world is coming. And maybe we should try to get ahead of that. Just my agent Stoker is facing the loss of his partner and is not really necessarily sure he is up to the job. He is, you might say, thrown into a gray zone where the rules are not clear, right.

Alex Ferrari 1:12:16

And I've heard that before. I've heard of that before.

Brian Nelson 1:12:19

And it's very it's up to him to figure out how to persevere, but perseverance in his case also requires in every episode, the examination of some artisanal cocktail,

Alex Ferrari 1:12:33

Obviously,

Brian Nelson 1:12:36

Which is one of the easter eggs that we put into every episode we also managed to put into every episode a little bit of baseball trivia, we also managed to put into every episode, an actual real world indie bookstore that we're doing a pro bono shout out to ah, that's amazing. And yet in every episode, he also deals with schizophrenic AI and sentience mold and demon where cats and a number of you know terrifying other sounds that this fall into another another one of our loglines for the show, which is think of it as CSI apocalypse. So so we cooked up this show we approached wonderful actors who are not household names but who you know through you know being fans of television and share with you who've been a bunch of people from altered carbon Amy Hill from Magnum P I. You know, we're our biggest name probably is our announcer and and later the voice of the night brigade is is Emily de Chanel. Wow. But also Peter Jason from Deadwood

Alex Ferrari 1:14:09

I do do do do a voice. Do you do a voice in it?

Brian Nelson 1:14:12

I do not do a voice you show you sit back No, no actually because we thought you know what, we're going to do this exactly like we would if it were not the shutdown and we're doing it for live TV. So all the actors are are being paid sag minimums and you know, Chris and I created knife brigade LLC as a SAG signatory. And yeah, it's funny, one of my high school friends just wrote me and said, You Aren't you doing your voice and this and I, you know, actually I, I love all of all of the voices in this coming from the universe of actors that Chris and I know and love that we've just always been dying to do something more with. That's and we brought in and we brought Actually, you know, directors that we love to So, the So, the the, the pilot and the finale are directed by Rachel Talalay from Doctor Who and Sherlock and, and Superman and Lois. Several episodes are directed by us Scott who's done everything from for color girls to swat MJ Bassett, whom I met on des Vinci's demons and nightflyers, and also did altered carbon does does a block of three episodes. So, so we've been having a hell of a time. Our sound design is by our our CO producer, Patrick Hogan, who currently does sound for little things like Cobra Kai and so forth. Our line series and amazing woman named Dana Brower, who I met on nightflyers. Our music we have a theme music by an indie composer we know named Christie Kuru we have entitled music by Portland Indie band, the parson redheads I mean, it sounds awesome. A lot of elements here you should listen I rather

Alex Ferrari 1:16:13

Where and where can and where can people listen to it?

Brian Nelson 1:16:16

Wherever you get your podcasts.

Alex Ferrari 1:16:19

And what's the name of the show again once again

Brian Nelson 1:16:21

It's Agent Stoker.

Alex Ferrari 1:16:23

Okay, so everyone listening

Brian Nelson 1:16:26

Bergerie that you can find on Spotify or Apple or you name it it's it's out there and and you better find it before it finds you.

Alex Ferrari 1:16:35

I will put it I will put it on the show notes. One last question three screenplays, three screenplays every screenwriter should read

Brian Nelson 1:16:47

Ooh you should have warned me because you know this sort of thing that like a certain questions that when people people ask them of course the things that you think go out of your head right you know I literally keep a posted here so that when people say what have you been watching lately? I have the answers so that I'll remember this otherwise you know you go right I have been watching things what are they so look ah we you talked earlier about night nights screenplay for unbreakable. It's incredible. I remember reading it back when I was starting out and I've like saved it I've still got my copy you know, it's it's, it's I would recommend that to anyone. This might not be this might be an unexpected answer. But when I think over the years of like pilots that I've read and blown me away that you know that there there have been there have been shows that there have been pilots that I that I I might recommend but I also when I think about screenplays, I am going to I'm going to toss in the third man I love the third man I think about that all the time. A screenplay that I might not recommend except I love it. It's structurally a mess. Well, it works. The best movie ever made maybe is the big sleep. Oh yeah. Yeah. I was hired on altered carbon in part because I came into the meeting and I said, you know, this story is like the big sleep and Lita calligraphic greatness was like, Yes it is. I'm so happy you know that. You know, so So I think about the big sleep all the time. I I'm not stopping it three. You're doing dirty pretty things. Dirty pretty. Is is is is an amazing script to me. You know, it is exactly what I've talked about. It is a guy thrown into a place where the rules are not clear. And now he has to find ask himself what am I capable of to faceless? I am a giant fan of Days of Heaven. The Terrence Malick masters I I'm a big fan of neem Creek. Yeah, yeah. Which I think is a very under discussed film. But again, a film where people discover what they're capable of that they never wanted to know about themselves. You know, I, that's five.

Alex Ferrari 1:20:11

I think you're good. You're good. You're good. We could keep going forever. I mean, we could do the podcasts of just like scripts you should read. And we just do like 20 every episode. Fair enough. But that was excellent. Brian, I know we can keep talking for another few hours, but I appreciate your time. Thank you so much for coming on the show and dropping your knowledge bombs on on our tribe. So I truly appreciate it. My friend. Thank you so much.

Brian Nelson 1:20:36

It's my pleasure. Great, great to talk and I will see you again when you least expect.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

Please subscribe and leave a rating or reviewby going to BPS Podcast

Want to advertise on this show? Visit Bulletproofscreenwriting.tv/Sponsors