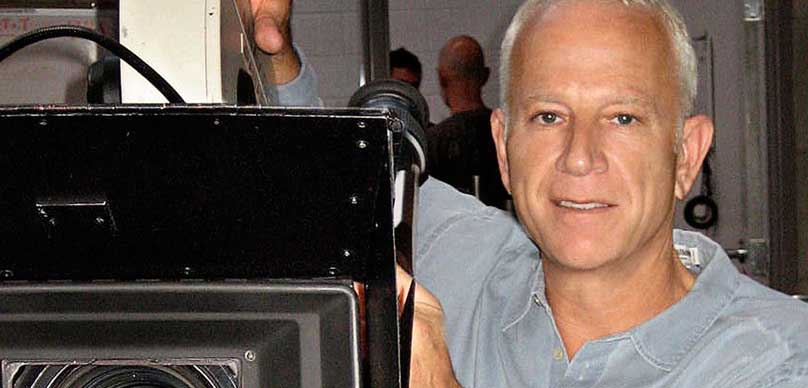

Today, we are hearing from one of the cultural influencers of the 90s film industry, and that’s non-other but Gary Goldstein, producer of the iconic rom-com, Pretty Woman, starring Richard Gere, and Julia Roberts.

A man in a legal but hurtful business needs an escort for some social events and hires a beautiful prostitute he meets… only to fall in love. The film’s story centers on down-on-her-luck Hollywood sex worker Vivian Ward, who is hired by Edward Lewis, a wealthy businessman, to be his escort for several business and social functions, and their developing relationship over the course of her week-long stay with him.

Pretty Woman was most of your introduction to Gary’s work, but mine was Cannibal Women in the Avocado Jungle of Death.

I know. After all these years, the title still makes me chuckle. Years later, I would reference the title to people. And in case you were curious, Gary goes into the movie title origin story in this interview.

Gary films have generated well over one billion dollars – consistent box office hits. Pretty Woman, for example, grossed $463.4 million – more than 30 times its budget. After the massive success of Pretty Woman, Gary collaborated once more with his filmmaking partner, writer, Jonathan Lawton to produce the action thriller, Under Seige in 1992. Like Pretty Woman, this too performed successfully at the box office and critically – including an Academy Award nomination. An ex-Navy Seal turned cook is the only person who can stop a group of terrorists when they seize control of a U.S. battleship

As an undergraduate student, Gary briefly did talent scouting for Columbia Records and is credited for producing music concerts and cabarets for Berkeley, where he studied.

After college, he practiced law briefly as a criminal defense attorney in San Francisco. Soon, he lost interest in the legal field and sought out a passion. Film and TV became the apparent choice since he had lots of friends who were in the business he could learn from. A year later, Gary opened up a management company where he put his talent scouting skills and experience to work. There, he worked with writers and directors.

By cosmic aligning, he met the young brilliant writer, Jonathan Lawton who wrote the script that became Pretty Woman.

In 2013 he authored Conquering Hollywood: The Screenwriter’s Blueprint for Career Success, which is a compilation of strategies to help anyone; whether looking to sell a spec script, option a screenplay, land a writing assignment and get hired, attract an agent, or manager of your dreams…or get a producer to take a meeting with you.

Gary blessed us with knowledge bombs in this interview, including tips on entrepreneurship and film as a business.

Enjoy my conversation with Gary Goldstein.

Right-click here to download the MP3

LINKS

- Gary Goldstein – IMDB

- Gary Goldstein – Website

- Book: Conquering Hollywood: The Screenwriter’s Blueprint for Career Success

SPONSORS

- Bulletproof Script Coverage– Get Your Screenplay Read by Hollywood Professionals

- Audible– Get a Free Screenwriting Audiobook

Alex Ferrari 0:15

I'd like to welcome to the show Gary Goldstein, How are you doing, Gary?

Gary Goldstein 0:18

I'm fabulous. Alex, how are you?

Alex Ferrari 0:20

I'm doing great. Thank you so much for coming on the show and, and dropping your knowledge bombs on our tribe today, sir.

Gary Goldstein 0:27

It's a pleasure. Thanks for having me.

Alex Ferrari 0:29

So, before we even get started, I need to I need to bring something to your attention. There was a film you made that had a very big impact on my life, and it's called cannibal women on the avocado jungle of death. Now, with that film, I was working at the video store in 1980, that my audience is tired of me saying, Oh, this video, so I am going to have a guest that impacted me during that time. I always bring it up. It was a it was 89 if I'm not mistaken, and that was a year into my a year, year and a half into my time spent at this video store. And I remember coming in it came into the store. And I said, Oh my God, that's amazing. Who the hell made this movie? And oh, my God, that's the greatest title of all time. Years later, I would always reference that title to people in like, the 80s were crazy. They even made a movie called cannibal women in the avocado jungle. And it was like and there was another one called the sofa. The killer bimbos. And there was and there was like, you know, girls, it was insane. But I remember that those those are the titles that I just stuck with me so much, because it's such an amazing title. How did you get involved in that? How did that come to be?

Gary Goldstein 1:41

It's actually a really fun story. So as you recall, because you were there at the time, in you know, I at the time, when I moved to LA I really didn't know a soul. I didn't know it look about the business. Other than I had a dream, I was driving to LA whatever fitting my Karmann Ghia came with and everything else left behind. And within a year or so I came here in the early 80s. And I formed I was a soft defrocked attorney, I was a criminal defense attorney up in San Francisco. I did not want to be an attorney. And I didn't know the job definitions of the film and TV business. But within a year or so I learned I found some mentors and friends. And I ended up opening up a management company. I wanted to work with writers and directors. So I formed a literary management company. And it you know, the first couple several years were pretty Rocky. But I figured it out. And it started to become a really good business. And I really enjoyed it. And because I was new my clients were unknowns with virtually no resume or a little resume. Anyway, long story short, I'm going to start at the beginning. So I bought one of the first Mac computers in the 80s. And it came in, you know, a box the size of a refrigerator. But you couldn't plug it in, it didn't do anything. And so I ran across it, I realized that a friend of mine, this woman, she was a screenwriter, and she was writing on one of these machines. And I said, How did you do that? Who programmed that for you? And she said, Oh, call Jonathan and I call this fellow Jonathan. He comes in he's 23 really brilliant guy very quiet. And he programs spent three weeks in my office, programming this darn thing and did a brilliant job. And along the way at the end. I was asked him a bunch of questions. And I learned he was a film school dropout. he'd written seven scripts, not a human had read one of them. They were in his little one room studio apartment in the rampart district of Hollywood. And I said, Well, you know, listen, let me read one of your scripts and and and if I like it, I'll help you get an agent. Well, long story short, I read three and I said, Forget the agent. You're good. I want to work with you. His name was Jonathan but he's also known as JF law. And then he was the guy who, amongst other things, wrote the script that became pretty woman. So you know, you never know where the good in the universe coming from. Anyway, so I now I have I have a great client and I have a computer that works. And life is great. And we're making hay, but I you know, we got to 1988 in the Writers Guild went on strike. So it shut all production down film and TV. So that was really weird. Yeah, I didn't want to sit on my hands. So I went to Jonathan and I said, Look, you've always wanted to direct I think I want to flex my producing muscles. See if I've got a producing muscle. And, you know, desktop, one of your college scripts, I'll go out and raise whatever I can. And we'll figure it out. You know, we'll be Dumb and Dumber. We'll go out and gorilla play like gorillas and make a movie. Anyway, long story short, so I went out looking for money, and I went to If you remember, do you know Charlie band? Name center? Yeah, Charlie band was the owner of a company called Empire pictures. Oh. And it was like a b minus Film Company. I'm putting it mildly anyway. So he ran this operation. And the way they made films back then was he would put together this gorgeous artwork on a glossy foldover. He would have a film title, he would have images, he would have a paragraph summary of the story. And then he would have a credit block. And it turned out I learned, I said, Who are all these names in the credit block? And he said, oh, they're the names of all my wives ex boyfriends with their first and last names mixed up and said, Okay, fair enough. And he would take these to the different film markets, me fed AFM, etc. And if buyers bought it, he had the money to go make the film. And if not, he threw it in the trash. So I went to him to to raise money. And he laid out a bunch of these cards. And he said, pick one. And I'm going to give you $200,000 whichever one you pick. And the titles were absolutely embarrassing. It was spaceless in the slammer. He had one called Parana women. So I said, Well, alright, I'm going to pick Parana women. And I said, you know, is it or is that carved in stone? Or can I change the name? He said, You cannot change the name. That's my name, you may not change the name. And I thought about it. Okay. But you know, people might think we're taking ourselves seriously. So can I add words to the end of it? And he said, Yeah, you can do that. So the film started as Parana women in the avocado jungle of death until we got the lawyer letter saying Turley, Ban has stolen our title. And you you can't use it. So it became cannibal women in the avocado jungle of death. You know, which was, which was for Joseph Conrad. We always say it's a 10 minute spoof comedy based on Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness. But we, we basically had a four week period before we were supposed to leave to the Sundance Institute for their production lab. on another project, I was gonna say, Don't tell me the cannibal women. They have a lot of fun dances about it. Not exactly. It was actually 3000, which was the the early version of Pretty Woman. So we had four weeks, and I said to Jonathan, whoa, whoa, yeah, let's make it when we get back. And you said, No, I don't want this hanging over our head. Why don't we make it before we go? And I said, Yeah, that makes sense. Let's do it. So we basically had, you know, two weeks of prep. We didn't have a crew until the second week, we realized we were missing something. And we shot it in 11 days and edited for three and deliberative as as is. And off we went to Sundance, but yeah, we had we made every mistake known to man, but at the same kind of way too much fun. And then we had, you know, listen, we had Bill Maher, and we had Shannon tweed, and we had Adrian barbeau. It was a riot.

Alex Ferrari 8:25

And the funny thing is that people don't understand that then in the late 80s, early 90s. I mean, essentially, all you needed to do was almost finish a film and it was sold. You wouldn't. If you just if you made it past the finish line and delivered a movie, you're going to make your money back because there was just no competition. I remember watching everything that came out every week. But literally every film that came out every week, which is probably five or 10 on a really great week normally like two or three new releases every week. And one right one of those one of those weeks is cannibalism. an avocado jungle is fantastic now, now I can diabetes, because now I know where that's okay.

Gary Goldstein 9:03

Yeah, I mean, it did make it Paramount Home Video. So it was out on VHS and ultimately DVD. And then I forget the platform, but it ran on it actually ran on cable for like, I don't know, 15 years or so.

Alex Ferrari 9:17

And it was constant. It was a constant. It was always Oh, and by the way, just so you know, one of our best selves and one of our best renters and just you know, one of our he was one of our best pals and little mom and pop little mom and pop shop that I worked at was it was insane. Someone came in like, well, that's going to be fun. It would be like predator, and then cannibal women the avocado devil that I'm like, watch one fruit for the action. Watch the other one just to have a great time. And as long as you don't take it seriously, it's going to be it's going to be worth your dollar 99. That's hysterical. So Alright, so you work on pretty woman with You know, it's a classic now and when it came out, I mean, people again, who weren't around during that time, it was a phenomenon. I mean, Julia critics made Julia Roberts who she was who she is that you know, Richard Gere was Richard Gere already, but it just completely exploded into another stratosphere after that. I heard the stories because we have a friend and comments on when we need that book. You know, he was my instructor, Walter, who was my instructor and an associate producer on and I think he just needed a second unit that one but associate producer, and I think he worked with Gary, he came over with Gary from happy days. I remember. And yeah, I think you're I think Gary Marshall, the late, great. Director. Now I love to hear the story from your point of view. And now I heard about 3000 that you haven't bought $2,000, which was the original title. And the original ending to Pretty Woman, not so uplifting. Boy, let's just say boy does not that girl, and then some. And there's a bit darker, bit darker ending. But Gary came in and kind of Gary marginalized, it essentially just made it a little bit more to tell me from your point of view. And from the screenwriters point of view. How was that process? Well,

Gary Goldstein 11:21

I mean, it was fascinating. And what had happened was I had optioned that project, you know, I got people back then paid and probably still do pay a lot of attention to the projects that get selected versus Sundance. Because I wasn't a big, you know, I was not well known, my client was not well known. But when people saw that our project was picked for Sundance, the phone started ringing. Long story short, I optioned it to best Ron. And it wasn't all that terribly long before best run, let us know they were going into bankruptcy. Right. So we got it and got it and turned around, who transitioned over to our notions, relatively new company back then, which was new Regency. And so I optioned it to new Regency and, you know, a similar experience like nothing terrible, but we weren't getting financing. We weren't getting a cast. Richard Gere had passed on it went to him while it was investor on went to him again at New Regency and he passed on it both times. Despite edlow motto, his agent bank banging his shoe on the table saying you got to do this, you got to do this. Anyway. So I had sent that script, kind of out of frustration, we were in the doldrums, I sent it as a writing sample. To a senior VP over it touched on the sister Disney sister label and it was supposed to be here's the setup, you know, we're gonna come in in a week, and we'll pitch you to Disney appropriate stories. This one's not for Disney. It's about a working girl. And the phone rang a few days later. And they basically said, we want to buy it. And I was like, Did you read the right script? Anyway, long story short, it turns out that they were going into production with with Gary Marshall is the director and the full complement of production personnel diet, you know, Diane critten, and casting, etc, etc. On what about Bob, but Michael Keaton, who was originally going to be a play that lead his deal blew up, for whatever reason, I don't know. And they had this sort of gap. And they looked at our film and said, you know, we could flop this in and have you put dairy on that film, etc. So we went in for a meeting. And you know, it's very unusual. You usually meet with an executive, maybe two, there were like over 20 people in the room. And it was Gary and his team and it was all new Regency and it was, you know, I mean Katzenberg in the room and David hover and the president this to me, it was like who's who? And long story short, after the meeting, settle down. And and David, the President, his studio was speaking, he turned to he turned to me and said, so on the Disney lightened scale, this is a four. And we would like it to be a seven. Can you do that? Well, you know, even if you've never heard of the Disney lightness scale, you sort of get what the question is. And so I just, I sort of looked pensive noticed everybody in the room staring at me, and I smiled, and I said, Yeah, we know exactly how to do that. And, you know, if you had no idea, and there's no idea how you're going to do that, and I didn't matter we'd figure it out. Yeah. Look, I mean, if you look at it, if you go back and look at it, I mean, it's a Disney movie touchstone obviously with the adult version of you know, the adult version with downtown Beverly Hills, which was the launch of it, and it was what kind of brought Disney back out of it was almost bankrupt at a certain point when Eisner and Jen Katzenberg shut up but even touchstone you're making a movie about a working girl about a prostitute and how that movie is looked upon. Now is this just wonderful rom com like the enemy of Iran calm almost, is on paper absurd. But if you've seen the movie, you understand? Yeah, well, what's absurd is that they could see in that original even the remote possibility because the original, let's just say it was edgy, it was not, you know, there was nothing warm and fuzzy or comedic about it. It had some tones to it that were very dark or dark, not dark, but you know, edgier than certainly the rom com version. But But you know, God bless they figured it out and and then put it to us to figure out how to transition it. And the only thing I really said to the writer Jonathan was like I'm, we're gonna make this deal. And my The only condition that's, that's, you know, live or die is that you have to be guaranteed the first rewrite to break the back of it as a comedy. And then they can hired I know, they're gonna fire you immediately after the first draft. And that's okay. expect that. And that's what happened. They hired three other writers.

Ironically, the first writer they hired made it even darker. Which was weird. But then they brought in Bob garlin, who's wonderful, the guy who wrote the electric horseman, and he just polished all the business dialogue. But then they brought in Barbara Dennett, benedek, to do the final rewrite. And she basically, one day whispered in my ear and, and said, I you because I was nervous. It's like Barbara, which, you know, what, what's the direction here? Where are we gone? And she said, you know, frankly, Jonathan's draft was what the film should be. My job is to take it as, as close to that as I can, making this studio believe that we followed all their notes. And that's kind of what happened. So we ended up with with a script where Jonathan got sole credit. So yeah, sole credit because it really was his rewrite. Now, that's not to say it was the film. It wasn't. There was, you know, God bless Gary Marshall. I mean, we'll go back, I'll tell you the story about how we got Joey on how we got our cast. But the fact that we inherited Garry Marshall was such a stroke of galactic good fortune like to get. And I honestly, I never would have thought of him as a director of this film, certainly not the way it was originally constructed. But the fact that we got Garry Marshall was truly miraculous. So I give very enormous credit, it was Gary Marshall alized. He is, you know, we sort of had a rule of thumb in production, which was, you know, shoot, you know, what, when one take is scripted, and then let's play let's improv because that's what he does. And he has such he had an and is the king of finding that that common heartbeat, he knows just where to find the magic. And he gives enormous freedom, not just the actors, which he did. But the whole set, we had an open set, it was full on participation, you know, of craft services had an idea, we want to hear about it. So, I give enormous credit to Gary, I give enormous credit is starting with the writer Jonathan but enormous credit to Gary Marshall, without whom this film wouldn't be what it is. And also to the actors. I mean, there were stunning moments where, like the there's a scene where she's on the balcony in the penthouse of the hotel, and she talks about I won't settle I want the full, I won't compromise, I want the whole dream. And that was not written that way. That was just Julia. Just doing a high wire act going with her character, where she needed to go. It was stunning. And and then there were other, you know, like, that was just the ethos of that set, was like, let's, let's all just give our best. And actually, Garry Marshall, you know, there were a bunch of what we call fog, friends of dairy. And some of them were, you know, in this in different scenes, some of them were in the crew and, and then some were just visitors to the set like Martin Kearse Feld, who, I think had worked with Gary Marty had worked with Darien overboard and one of one of his other films. He was a creative consultant and he was on the set one day, that scene where he's got her. He's taking Edwards taking Vivian to her first ever opera at the war memorial in San Francisco, and she's in a red Cinderella dress and they're in the elevator. Whatever line was in the script, I don't remember to be honest, but we were looking at it wasn't really working. So we're staring huddled around video village looking at our leads inherit, you know Full wardrobe. And suddenly this voice which is Marty kerfeld. whispers, what if she were to say, in case I forget to tell you later, I had a wonderful time tonight. Oh, and you? You could have heard a pin drop. I mean, I just, I was speechless looked at the sky and thinking God spoke. Exactly, you know, Never have I heard in the essence of a character summed up in one line so beautifully. So, of course, it worked and stayed in the movie and whatnot. But yeah, I mean, I think there were a lot of contributions. We can't we can't discount the talent, we certainly have to give, you know, enormous enormous credit to this film for one to one person and that's Gary Marshall.

Alex Ferrari 20:51

Yeah, and how did you get Julia? How would because Julia, just mystic pizza, if I remember correctly, and she she was she was not lead by any stretch? Yeah, no,

Gary Goldstein 21:01

no, but the fellows who produced mystic pizza, were friends at the time. I haven't seen him in 100 years. But Mark and Scott, before they lock picture that as as we often did, you have friends and family screening, and you you know, please kick the tires, before we lacked texture was Give me your criticism. And so I showed up for that screening. And when the lights came up, I basically said I you know, there were and I there were a good number of people there. But I basically said, Absolutely no criticism, I think you've got a gem of a cell and amazing cast, well written, well produced. Don't mess with it. It's good to go. But by the same token, I don't know who that girl is. But that one, I need to know her. What's her name? And this is Julia Roberts and blah, blah, blah. And I would you introduce me and they said absolutely. Well, Julia and her her then I believe it was her manager, Elaine Goldsmith, I forget they read it and immediately like within a few days, they Julia was attached and she stayed attached for the three years before I got it, rocking it, Disney. But you know, at the time, once we got it set up Disney Disney really wasn't interested in Julia Roberts, they didn't know her she was in fairness, she was not yet known to the American public ordered the studio system and despite the fact that she had completed production on a yet to be released Steel Magnolias. So she was she was already well on her way. I mean, her, her career arc was inevitable. In my view, she was meant to be a star, I think pretty one was just a really extraordinary fit for her. But I knew that the studio was screen testing and auditioning and meeting with every name in the book, both male and female for the leads, and so I didn't really have a chance to put my argument forward for Julia until we had a male lead and I just, you know, basically let them know that you know, really we wanted Richard and he had turned us down twice but we never had a major studio a major director and a major checkbook and maybe we should have a run at that. And they did and they made him the you know, the Godfather offer and he didn't refuse and actually it was a tentative yes it's a sweet story a tentative Yes. edler mana was was, you know, a real champion. And so, at that point, I went to Gary Marshall and, and basically said, Look, there's this you know, I know we're meeting a lot of talent, a lot of females for the lead. But there's this one young actress I'd love you to meet. But I'd like to put a you know, a condition on it, which is to say I want you to meet her alone. I don't need to be no one else should be there. I said by the way, there's a warning that goes with it, which is you're gonna fall in love. Just be aware. So, you know, that was kind of sealed the deal. Anyway, he met with her and he absolutely said yes. You know, this is like, She's amazing. And so we we did a he flew her to New York, to meet with Richard. He was going to try and put put the bow in, you know, tie a bow in this. So he took her to Richard's apartment in New York, and they walked in and they were introduced Richard and Julia and apparently as the story is told Gary, after a couple of minutes excused himself said, Yeah, I'm gonna go to the bathroom or I'm gonna make the call or whatever he was going to do. And he walked away to another part of the apartment. In 15 minutes later, he called Richard cell and from the back of the apartment, is it How's it going? And Richard was talking to him. And Julia science and posted on Richard's desk, grabbed a pen and wrote something on it and tore it off and handed it to Richard. And all it said on it was please say yes. Oh, right. Oh. And of course, right there in the moment, he smiled and over the phone to Gary, he said yes. And that it doesn't get any better than that.

Alex Ferrari 25:28

I mean, and just that story alone, it kind of permeates the entire movie, that heart that thing is there. It's it's undeniable, almost the same TV woman a million times during over the last 30 years. It's just something that you just one of those films that you do. And Julia, we she was Oscar nominated for that as a mistaken. Right.

Gary Goldstein 25:50

She was she was she got a nomination and as she did for Steel Magnolias. And yeah, I mean, she came out of the gate being, you know, all really all the time. But yeah, so it was it was a blessing. They did you know, we did a screen test, just to sort of finalize it. And all I can tell you is, you know, even before they started rolling camera, it was it was the needle just blew right off the far right of the chart.

Alex Ferrari 26:23

Yeah. Yeah. And it's Yeah, I just, I just still remember going to see it and my mind being blown. And of course, that also has a video show with a big rental. We had more than one copy, if I remember correctly. Now, you you, you had a nice little run there for a minute. A few a couple movies later, you also worked on under siege, which, which was a massive hit. And pretty much if I'm not mistaken, still the biggest hit of students adults career. I'm not mistaken. It might be. But I think it was his biggest I I'm not

Gary Goldstein 26:59

absolutely sure Alex, I know. It was huge. It's not, you know, it's fun to see. But we're, you know, it was it was a big deal for Warner Brothers. It was actually the first time they released a film of that type in in October, and it set all kinds of records. I don't really know. I think it's certainly one of his biggest if not his biggest box office experience. Yeah.

Alex Ferrari 27:22

And I know Tommy and Tommy Lee Jones was just amazing. Gary Busey amazing in that zone. I mean, it was, it was so he has so much support around him. I mean, a lot of support around him. And the Africans, the director was, he was also like, Andy, Andy Davis. Yeah. And it goes out the fugitive.

Gary Goldstein 27:46

Yeah, yeah. I mean, he's no slouch. No. And Andy was amazing. He had worked with Steven once before. And I also loved his and ano his work with Peter McGregor Scott, who's no longer with us what an amazing gentleman is so good at what he did. He was sort of a hands on line producer. You know, he was, anyway, they were a delight to work with. In fact, I don't know if you remember, there was a party scene in in the battleship for the admirals birthday. And there was a jazz, a jazz band that played jazz, the jazz band was led by Andy Davis's brother there good Chicago boys.

Alex Ferrari 28:28

nepotism at its best. That's awesome. That's awesome. Hey, I do the same thing. But I remember that movie really well, as well. And that was also a fairly big hit for us for you. I mean, when you mean, obviously when pretty woman and then under siege, you know, a couple of a few years later came out. The town looks at you very differently after a massive hit. And the doors all open. Can you talk a little bit about being in that kind of? I always like to call it the center of the hurricane? Because I mean, as a producer, people start picking up your URLs or zippers or on on pretty women. Okay. They pick up the call? How is that? What is it like being in that space in Hollywood, especially during that time, which was a pretty insane time.

Gary Goldstein 29:14

It was a pretty insane time. It was actually a brilliant time. Not just because of the studio, the studio system was so different, that it was run by years before the studios were bought by these larger companies. But because there were I don't know the number. But you know, it seemed like there were almost three dozen maybe it wasn't maybe there were two dozen really robust indie companies to handles invest drones and so on and so forth. And they were making amazing, you know, they were making a platoon and Salvador and dirty dancing and all these, you know, just their output was equal to the studios. And so it was a really good time to be in front of or behind the camera. You know, whatever you did, it was a good time, and I Um, and I think that, you know, I sort of I sort of, I didn't grow up in the business, I was still relatively young in the business, to have a film like pretty woman, be your first studio film. And I mean, when we were making it, the truth is we had a reputation of Oh, that little film in trouble. Because the but we were extraordinarily low budget for a studio film, by Studio standards. And we were everyone knew we were doing a lot of improv and that we were trying to turn it from a, you know, because it had been so widely read and well regarded as the original, that people knew how big the transition might be. And so we had sort of a, you know, oh, it's a little film, oh, they're trying to find their, their tone, and so on, and so forth. So when it came out, and did the kind of business that it did, and it was in the theaters actively for six months. And it was doing it was, you know, doing five figures, every, every every week. And in fact, it went up the second week. So we knew word of mouth was good. We sort of do from the test screenings that we've that we might have. Not a hit. But a successful film, right, by by minimum definitional standards. We had no idea that it was going to be touched a chord the way it did. In fact, my concern, and I don't think I was alone in it was that we're going to get pilloried. I mean, it was the era of lurk Gloria Steinem. And you know, when, and I thought putting this out as a role model, I don't know. But I think we have to be prepared that there's going to be some upset people. And ironically, that never, that never came to be, in fact, the very people I was concerned about embraced it, and came up very publicly in support of it. So it was interesting. But I think I was to answer your question, Alex, I think I was pretty naive guy at the time. I mean, I, I was grateful. I was excited to be welcomed into the game. I don't think I was like, sitting outside of myself looking at the situation going, Oh, my gosh, guess guess what just happened. That wasn't my thought process. I was grateful to be able to reach out to people and talk about other projects. And you know, and just happen to have a film out in the world that was doing well. I think I started to figure it out a little bit more with under siege, because, you know, now it wasn't a one trick pony. It was, you know, here was another really solid, solidly performing film with named talent and the big studio and all of that and respond to SQL, etc. So, you know, if that was when I sort of realized, oh, gosh, you know, I there's, I always thought that no one's unreachable. You just have to know their assistant, and then you sneak in. But yeah, really? Yeah. If you want to own the town, just own the assistance, and you're all you're all good. But I think at that point, I started to realize, Oh, you really have established sort of a beachhead, and you can have access when you need it, whether it's agencies, your studios, your production company, whatever it might be. And, you know, I mean, I think the, you know, a good example of that. What one of one of my, one of my favorite films that I've been involved with, anyway, was a film, the film the madman prophecies. Well, and the reason why is sort of the nonpublic reason why I say that is because the writer who brought that to me, was one of the CO writers, he was a he had a writing partner prior. And that team was it's interesting, their attorney, their attorney called me and said, I have this team of writers, and they had this script called in dark territory, and their agent shot to everywhere and everybody passed on it, but would you read it? It was like, that's how is the dubious honor? Right. So okay, fine, send it over. I'll read it. Long story short, I said, I know I like it. I think I know, I think I know if we can change the title and make these couple of changes, send the writers in let's talk and they did, and I sold it to Warner Brothers who had passed on it 90 days earlier. And it became ultimately the sequel to under siege. But one of those writers then later, some years later came to me with this project, the Mothman prophecies. And honestly, Alex, when I read it, I was his sucker punch me in the third eye because not in a absolutely literal sense. But when my best friend My dad died unexpectedly, the next year and a half, two years were that that's that film son. My experience it was like that, almost losing your tether. And assuming everything, all these weird things are happening, because it's your dad trying to reach back out to you or your loved one trying to reach back out to you. And it was a very, very odd time where you're sort of walking into worlds. And when I read the script, I thought, oh my god, I don't care if same thing. It had been shot by the agent, everybody had passed, and I didn't care. I said, Let's, if I can find one company that didn't pass on it, and I did, there was one company, Lakeshore great company. And I said, I don't care. This is going to be a private homage to my dad, I am going to get this film made. And the team over at Lakeshore read it and they they said it was, you know, fascinating and amazing and wonderful. And thank you. It's gonna be a pass. Yeah, very Hollywood. And and there was a long pause. And I basically said, Listen, I really appreciate it, guys. I love what you said about the script, but I'm gonna have to pass on your pass. And so I you know, look, of course, you can pass but I just Will you give me a face to face before you make it official? And they said, yeah. And I think there are two things that were at play. One is I went in and never talked about the script. It was a very short meeting, I basically went into 15 minutes on who my dad was our relationship and what what, you know, like the, the crack in the universe that I fell into, in my experience, following his death, and how we're all hardwired to understand the loss and despair that follows. And anyway, long story short, they turned their, you know, they huddled in they they changed their mind. And they came back and said, Yeah, you're I think we think you're right, we're gonna go with this. And so I was able to get that film made, and I thought it turned out really well. I think it lived up to its promise. And I'm blanking at the moment, why am I blanking? Mark Billings, Mark pellington directed it. That's right.

Alex Ferrari 37:11

Well, I'll tell you one thing. I saw that movie once, and I will never watch it again. Because it terrified me. I was terrified after I saw that meld and I just like it to my bones. It's like very rare for a movie to like, hit me to the bone. I will not watch that movie again. Like I don't even like saying the name. It just freaks me out. It was it was a very, very well.

Gary Goldstein 37:31

Yeah. So I was very proud of that for for, you know, as a producer, but also as a son. And and I, you know, I think I can't tell you for a fact. But I will tell you my suspicion is that having had a couple of successes prior to that asked, it didn't hurt the cause.

Alex Ferrari 37:57

No, I did. And it did. Well, for my Android, it did very well. And then we need to box office. No, I mean, it's been it's remarkable the projects you've been involved with. And I have to ask you something, though, just because you told your story of how you, you nicely got into the business and how you were like, Well, you know, I'll just do this. And I'll do that and I get it. And you were coming from you know, you weren't coming like sleeping on couches, you know, you're an attorney, but you need and want to make the attorney. Where do you see people go wrong, when they try to break into this business? And I was like, the term breaking like, it's varsity. Like, you gotta break in and you gotta Yeah, like, it's not like, how can I you know, be part of a community, you know, how can I break in? It's always that, but where do you see people going? Because I'm assuming you've been approached a million times about, Hey, can you do this for me? Hey, can you get this for me? Where do you see what do you see people go wrong?

Gary Goldstein 38:52

Well, I think you just put your finger on. You know, you really just pointed right to it, which is people have this very unwelcoming story almost a sort of a monster story about how unfriendly and how close off is this thing called Hollywood, which is not my experience of it. I mean, I'm not gonna. It's not it's not a panacea. It's not utopia, but it's far from what I think many people attribute to it in their mind. And I think part of the and I also think a lot of people don't realize the value they bring to the conversation. They feel needy, they feel insecure, they lack confidence. I'm going to come back to this I just want to share one quick story. So years and years ago, there was a gal who had been a senior VP of had been fundamentally the head of business and legal affairs for a major one of the six majors. And she'd done it for 14 years. She was a force of nature. Everybody in town knew her. She was a get it done. are in really lovely. And one day she called me out of the blue, and basically said, Gary, I want I want to, I want you to coach me. And I was like, What? You're one of the most formidable people in the industry. I probably would love to learn what you forgotten. What, what, what what can I possibly help you with? And what she revealed was that she had been sort of a closet screenwriter at night and on the weekend, over the recent years, and she wanted to leave her executive suite position and become a full time screenwriters, she had just officially done that she had left the studio and was now a full time screenwriter. And what happens apparently, Alex, when that choice gets made, as they also give you a free lobotomy, you forget absolutely everything that you know, all of the fears, well, of all of the insecurity, as well as all of the of them ever going to be good enough. It's too hard. I don't know how it's too competitive, and all these stories rockin in your head, and it really starts to take effect. And I think that, you know, the biggest, I mean, there are a lot of mistakes that people often can or do make. But I think one of them is just not wearing their humanity upfront. So you see, you know, the biggest tool of a writer is the blind query letter, the worst idea ever taught to anybody on the planet, the most impersonal, like easiest to ignore, flying into the same inboxes. And by the way, they're all going to wet agents and producers, will you produce me? Will you represent me? No one's reaching out to mentor saying a cinematographer and editor a casting director, you know, like, people who are in the center of the ring? No one's knocking on their door. What could what what kind of relationship and what kind of community could you build? What kind of lessons could you learn? People are very narrow focus, very near sighted about things. And they sort of mimic other people's behaviors, it's a it's really not a very, you know, if you were in any other industry, and you said, I'm going to focus 100% my craft, I'm going to really ignore my marketing or my entrepreneurial or career, you know, the side, you'd be out of business. And you end up losing a lot of brilliant stories and a lot of brilliant storytellers because they just get worn down. But I think it's one of the biggest mistakes, I know there's a there's a long laundry list of mistakes, and I've made many of them myself, tons. But I think the one that really is most crucial is they get shut down. And they don't share who they the artists, the storyteller, the creator are, they don't share their humanity or their origin story, or why they're so deeply passionate and connected to this particular story. They hide behind the script cover, behind the project behind a blind query letter, and, and and they don't give people a chance to get to know, let alone champion them. So

Alex Ferrari 43:19

you know, I go ahead and interrupt you. But it seems such an interesting way of looking at it. Because, you know, I didn't when I was coming up, you know, you would just try to, you would just try to try to connect with, you know, a producer, a director, an agent, a manager, and after whatever, at such a superficial level. And that's what this whole town is built on, is a lot of these superficial relationships. But whenever you do connect authentically with someone I found in my career, that you hold on to these people, that they, you you because it's so rare to find authenticity in Hollywood. I mean, even if it's negative authenticity, and like for someone to say your script sucks. I'm sorry. At least it's something authentic, as opposed to it was great. It's fantastic. It's amazing. You should win an Oscar we're gonna pass which is the nicest. efuse Hollywood is the art.

Gary Goldstein 44:23

Yeah, give us the truth. Right? In fact, I I've often coach fuel instead, let the you know, rejection is your best friend. Yeah, because 99.9999% of all humans when rejected will react predictively you will not. You're going to do the one who takes a nice deep breath. And when you hear that you're going to smile. And you're going to say thank you, you can say but what would be really the most helpful, valuable thing in life right now for me, is if you do me the honor of sharing the truth, why why is this a pass for you? I want to learn and when happens is you're probably going to learn something. But more importantly, you've just honored them. And you bonded with them in a way that very, very few people ever Well, you've taken advantage of a moment. It's kind of like the it always tells me I had a actor friend. This goes back aways. But anyway, I ran into him one day, and he was in a he was he was really in a bad mood, he was in a funk. And I said, What's going on? And he said, I just came from this audition is a role I really wanted. And I didn't get the gig. And I said, Yeah, and so that's why you're all upset. He said, yeah. So tell me about it. What was the project and who was in the room? And he told me about the project? And he said, Yeah, and it was the casting director and the casting associate, and there was the producer. And I forget if the director was there, it's probably just the producer, and whatever. And I said, really, all those people were in the room? And do you feel you gave a great, you know, good, solid performance? You said, Yeah, but I didn't get the gig. as well. I mean, I don't want to be unsympathetic. But here's the deal. You know, I think you think the purpose of an audition is to get a job, and I don't, let's talk about that. Because you're going to live in a world pass fail, a RF note, no gray. And I live in a world where I think, Wow, every audition should be celebrated. And that it's not about the result is an opportunity, you're being invited to a party that you want to be invited back to. So you go into a room and you hug and greet and smile at everybody starting with the assistant, and then the casting people and then the producer, and then the director and everything, and you do it on the way back out. And you of course, you're going to give your best performance. That's just a given. But what you really want is to make them feel they've gotten a sense of who you really are as a personality as a human, not just as an actor giving a performance, and that they like you. And gosh, you know, he may not be right, there's a million reasons why you might not be right for a role in a moment. But they've got a lot of projects, and these people are serious people and you want to know them. And you you know, you you just want them to like you enough to think of you in the future. And if you've done that you just want that's that's the long game.

Alex Ferrari 47:15

Isn't it amazing that. And please tell me what you think that if you are likable, if you are someone that people can work with, and stay in a room with for 10 hours or on set with the third 12 hours, or when it's like hour 15 and OT and you're still got a good attitude. If you're that person, wouldn't you go out of your way to figure out how I can get in there, right now for this project. But I'm going to remember that guy or that gal, and I'm gonna find a way to bring them into what we're doing. Because we need people like that, because they might not even be the most talented. They might not even but that power of being likable. It's like the best advice I've ever heard. Like, for being film business, like Just don't be a dick. And the greatest, it's a great good advice. Good advice, don't be a dick. And not in that being that big will get you more work and more opportunities then. But that your experience as well. Like if you see someone who's just meant likeable, I think I could really work with this person, I got to figure out a way how to make this happen.

Gary Goldstein 48:24

I think that's only 100%, true 365 days a year. If you're if you're I don't care if you're looking for a production job or an acting job, or an agent or a manager, you know, it's like they the men, they're going to take the measure of you whether they're conscious or whether they articulate it or not. They're going to take the measure and say, am I going to be able to go the long distance with this person? Or am I going to enjoy this process? Are they going to contribute? Or are they going to be nagging at me and complaining? I had a showrunner there was an exact producer of a TV series that I was. We were talking about I was I'm always fascinated by the writers room, right? It's like staff. I just find that dynamic, so interesting. And you know it anyway, so I was I was asking him, I said you know what? What are you looking for? How do you build that team? What are the things that are going through your head? Look, it's really simple. It's 3am. We have until daylight to crack this thing that all of us have been banged on and unable to crack. We're all sleep deprived, we're exhausted, we're unhappy. We want to go home, we want to sleep in our bed. We miss our family, and we're hungry. Who do I want next to me? That's the pic. That's the image in my head who's the person and it's not about the most talented person. He used those words just like you did. He said, I will absolutely gladly take the second or third most talented person if they're the one I want sitting next to me

Alex Ferrari 50:00

Cuz I know I know a lot of very talented people who are absent dicks. And I wouldn't want to work with them. I just like, and I would take second or third tier, who's going to give it their all? Yeah. And we're going to get to the finish line, because really enjoy. And, and again, as I've gotten older, I've just realized that life is way too short. To just work with people who are decks. It's just, it's just like, I don't want to work with people like that I want to work I want to find good people who I enjoy this process with, because it should be an enjoyable process. We are some of the most lucky human beings on planet to do what we get to do on the archery Oh my god. Can you imagine

Gary Goldstein 50:43

being miserable or to be complaining? Doing what we do is like not acceptable. It's

Alex Ferrari 50:49

no. Look, and there's like, you know, you could be on the set of The Revenant. And, and that's a that's a tough shoot. You could be on the set of Titanic. That's a tough shoot. But even on the worst day, you're still being paid to play, to enjoy to be an artist and and that's such a rarity in this world. And I think I think filmmakers, I think filmmakers and screenwriters, they lose, they lose focus on that, because it just, you know, especially when you're young, you're out you want the I joke about this all the time, but I'm sure you've run into these, you know, it will be your with your work, where you when you look at the filmmaker screenwriters who come in with this entitlement. They're like, why hasn't Hollywood, you know, recognized my genius. I mean, I don't understand like, I'm such a good writer. Why haven't I sold 15 scripts already? And I should be living in the Hollywood Hills? Why have I not gotten that part yet? I'm obviously the best for it. Like this, this entitlement that comes into it. And it's I mean, I was like, when I was in my early 20s, I was just like, obviously, come on, when is someone going to recognize how amazing I am? And then the business goes? Do you have you run into that kind of scenario?

Gary Goldstein 52:06

I'm not I have no idea what you're talking about. I've never, I've never met an entitled creative in my lifetime. I'm sure it'll happen. But now that Yeah, yeah. I mean, I think if, if you could just give people a timeout, and say, Can we just set that on the sideboard for the moment? I want you to spend the next 24 hours, better yet the next 72 hours. With only one idea in mind, I want you to be 100% other focused? How can you contribute to them in that moment? Just flex the muscle?

Alex Ferrari 52:46

Oh my god, I tell people all the time. Then if you want to create authentic relationships with someone offered, you offer to be of service, don't ask when you first meet somebody? Hey, I know that, you know, Gary Marshall, can you send him my script? Like, obviously, you could pick up the phone and talk to Gary or to talk to Richard or talk to Julia or what whoever the you know, whatever connections you have, I just met you. By the way, I need you to do me a favor. What do you that happens all the time to me, I'm nobody. I'm nobody in my world. And I get hit like that on a daily basis by people. And I always tell people, if you want to build relationships, you need to be of service. I've built relationships over courses of three or four years, before I ever asked for a thing. Because I truly built a real relationship authentic relationship. And I was always there to help them. And then if I need some help, as a friend, you go, Hey, can you connect me with this? Or can you do that? And but that's an authentic relationship as opposed to five minutes after we meet. Can you hear that's my movie Gary, I need I need Can you connect me to half a million? It's almost

Gary Goldstein 53:57

what surreal is how constant that mindset. In other words, these habits that people have reaching out to people they've never met in person. Probably never had a single real, what I would call conversation. But they'll reach out to them and send their script or their real or whatever and say, Well you produce Will you work for me for free to produce this movie. It'll take you several years on your dime you know, it's brilliant. So I'm doing your favorite or conversely, you know, will you you know, Mr. Agent, Mr. or Miss Miss manager, will you represent me? Same deal. You can't think of a bigger ask. You're asking people who've made this massive commitment in life to what they what they do. And you're saying out of all the possible people you could collaborate with. For projects. Choose me now. I haven't bothered to introduce myself, then I haven't bothered to get to know what what you care about or what makes you tick. I haven't even done that really with your assistant because I'm afraid of Calling Strangers. But please, you know, and it's, it's not always because they it's not even that they necessarily come across as entitled or think thinking they're so grand. It's just a common behavior set. Yeah, it's just like, if you were in any other industry, period, full stop if you're in any other industry.

Alex Ferrari 55:37

Right. And like I was, I always tell people, if you were in the cookie industry, you wouldn't walk up to the CEO of a cookie company and going, Hey, I've got this great cookie recipe. I think it's gonna make you millions. Like, that just doesn't happen. You know, it's, we're such a group of iOS, call us Connie's, you know, we're Carnival folk, you know, we're just a unique group of artists that travel and set up tents, and we put on a show and we record the show and look like we're Carnival folk. And it's just such a remarkable, it's just such a remarkable industry. I love the I love it. I've always loved it. I can't quit it as much as I've tried. There's many times in my career the last 25 years that I've just like, I just kind of put it to something else. This is too hard. This is too brutal. And then like, like a disease, it flares up again, because I got bitten by the bug at that damn video store. And then I can't, I can't quit. Like, I can't quit it and nothing I do. I have to be around that I have to do what I love doing. And it's, and I'm not sure if that's, that's not the way the cookie businesses like you. I mean, I'm sure for some people, it's in their blood that cookies, but generally speaking. What? Well, yeah, I mean, it's it.

Gary Goldstein 56:53

I think, if you want to endure in and I do think that we're blessed to be in this business. I think it's a crazy business. It can be a shocking business, it can be an amusing business, it can be many things, it can be disappointing. But if you want to be in this business, if you're one of the cricket people, and you love hanging out with cricket people, and I don't mean cricket isn't, you know, dishonest? I mean, like, where are we, where our humanity, we're flawed, where you know, it's fabulous, right? We're stories, the people who are drawn to storytelling. Yeah, then you have to see it for what it is, which is, it's, if you can, if you number one, you got to be really determined. And you got to, you know, I mean, it's, it can't be a hobby, it's got to be you got to commit. And if you're committing, it's about building relationships. And it's about getting better at your craft. But if you do one without the other. And to build relationships, you can't be asking huge favors of total strangers, it's just that

Alex Ferrari 57:54

people are bigger. That's the way the world works. It's not the world words, I'm in you. You've mentioned it a bunch. I've mentioned it a bunch, but we call this a business. But no other business in the world that I know of, can drop half a million dollars on a product that could literally be worthless. You know, if you don't know what you're doing, you could I mean, if you spent a half a million dollars on house, there's codes, there's things that you have to pass through the inspection process. Even if you've made an ugly house, it's still a house, so it can live in it. But if you make an ugly movie, and I seen those movies, that it's money just flushed down the toilet, it's a remarkable business that way.

Gary Goldstein 58:39

Yeah. Yeah, no, it's true is true. And if you know, so you got to pay your dues. I mean, I think part of it is also I mean, when I started out, I was just so excited, I was wagging my tail, I was just so happy to be here. And if anyone would talk to me, like I okay, you made my week. But I, you know, I think that it's we're living in a different time. Back then, there was also still some, not the old studio system where actors were under contract, and they had to make six films a year, and they were paid very little. And, you know, but but that's sort of, like, we're gonna work you till you're brilliant at your craft. And people had long apprentice runways, right. It's also when there was not a thing about make or break the first weekend and, you know, with a huge marketing budget on a film, it's like it was a different time. And people really did develop relationships. They were working so much and for such a long time graduating without grand expectations of I'm going to be a producer, my first, you know, my first script. And I think that some of that is, you know, there's this perception that the business is contracted and I think it's just the opposite. I think it's an expanding business. You know, I just look at the demand for fresh stories in every format more formats than we're used to. It used to be just series in film. Now it's doc limited series and docu series and you know, you, whatever you, whatever you're excited about, there's a place for it. And there's more buyers than ever and, you know, more mouths to feed, so to speak. Yeah, so I, I think it's a really extraordinary time, but you got to kind of get old school, I think you got to, you know, be willing to actually meet the people that you want to endure, and have enduring relationships with, gotta get, you know, get over yourself. And, and, you know, be a little bit more, I don't know, look over the hedgerow, get a little generous, be sure your personality get, you know, pick up the phone, do something,

Alex Ferrari 1:00:50

you have to be vulnerable, you have to handle, you have to become a little bit vulnerable, just a bit, show people a little bit faster than near them. Because that's what people feel connected. That's what people connect to.

Gary Goldstein 1:01:04

And you know, what's interesting? I've always said it, you know it. And I think it's true of a lot of industries, I think, because it's about the human question, the human factor, I don't think it takes an enormous amount to shine to stand out. If you show, as you were saying, Alex, if you show a little bit of vulnerability, if you're a little bit other focused, if you're a little bit generous, if you're just a little bit of those things, you'll, you'll look like a rock star.

Alex Ferrari 1:01:33

Right? Because there's no competition, because nobody else is doing it, you automatically rise above, above the noise by doing that, and I did that when I was coming up as a PA. You know, I was just being I was always trying to be of service to people. That's how I got my first kids and got my first got jobs and all that.

Gary Goldstein 1:01:52

Yeah, and we talked about it before. But I think the other thing that the other the other oversight or mistake that people often make is, you know, they're so focused on the name on the door, and forget the name on the door. You know, like, by the way, if you're fortunate enough to develop some kind of connection with them. People who are successful, who've made it, no, it's a team sport, they didn't get there on their own. And they be very generous, they tend to be very available, they tend to be great mentors, and friends, whatever. But you don't expect that the name on the door is going to necessarily be available to respond to you. People in this business matriculate quickly there, they're vetted there, you know, like the assistance, the entry level, the creative exactly that all those low lying positions. Well, I did, I did this as a as a sort of off the cuff lesson for a group the other day where I just went on LinkedIn, and I typed in a keyword. And up came all these young looking faces. And I went one by one, and I said, I want, let's just go through the resume. And they worked at these five amazing companies. And they went to Harvard, and they went here, and they went there. And these are like the most vetted people. Otherwise, you're not going to be sitting on the desk of a great agent, or a great producer, whatever it is, and they are ambitious, and they're smart, and they need to grow their own relationships to have currency. These people need to know you as much as you need to know them, just get out of your own way Get to know them, because they grow we grow together and micro generations. And just make friends with a lot of people who are already on the inside but who are available. And, you know, the that's that's the may seem like the long game, but it's really the diamond land.

Alex Ferrari 1:03:42

I would agree with you 100%. One thing that we one thing that this business is known for is rejection. You're going to get 1000 nose before you get one yes. And everyone gets knows even students do project notes. You know, even Scorsese gets notes like I, I tell people that all the time and they go what I'm like scuba couldn't get Lincoln made, like he had to go. And Scorsese couldn't get some of his projects that like Oliver Stone is hustling for his next budget like it's it everyone gets knows, how do you deal with rejection and continue to move forward and not get decimated by especially when you're at the beginning stages when you don't have that armor and momentum to continue to move forward?

Gary Goldstein 1:04:22

Yeah, I listen to it. I'm not going to say I'm immune to it. I sort of flipped the script a little bit. I always First of all, I think that failure and success are the same exact goddamn thing. They're twins that were never really separated at birth. You know? I mean, it we've heard it 1000 times the famous quote from Thomas Watson who founded IBM, if you want to increase your rate of success, double your rate of failure. I think I'm doing a justice anyway. But that idea and I really don't I see is it's like on a spectrum. But wherever you are in that spectrum, including getting rejections, I always just reminded myself, what does that mean? That means I'm in the game. I'm making actions. I may be getting rejections, but I'm making connections. I'm being taken seriously enough to be in a conversation. So don't stop, just keep pushing forward. I figured, you know, if I really suck, then, you know, great, I'm gonna, you know, if this I'm not a big sports nut, but you know, I'd be batting less than 100. Right? Okay. But if I'm batting 50, and I get and I get enough at bats, am I creating insider relationships? Yeah, I am. I'm just failing a lot. And I'm learning from that. But I just want to make sure I'm on the court, not in the sand, I want to make sure I'm in the game. And to me, rejection is an opportunity to learn as it legitimately is, if you're willing, if you're ballsy enough to follow through, is that so you learn but it's also an opportunity, as we talked about earlier, to bond and really surprise people and take that level of reporting inch it forward, it's a game of inches, right and move it forward. And there's really no downside to it. You know, you can't it's like I don't I don't really take it personally. It's it's the old Maya Angelou thing. If I if I can let someone reject me and actually make them feel good, leaving that conversation, I have now one a new friend. So whatever was said, they're not going to remember, I'm not going to remember, no one's going to remember. But they're going to know how I made them feel and vice versa.

Alex Ferrari 1:06:47

Great. That's great, great advice. And I'll ask you, I'm gonna ask you a few questions asked all my guests. What is the lesson that took you the longest to learn whether in the film industry or in life,

Gary Goldstein 1:07:06

give yourself freedom, give yourself permission, the shit that you worry about. And I think there's over 8 billion folks on the planet at this given moment. Not one of those 8 billion people are worried about the thing you're worried about. You know, get get out of your own way. Don't you know, this is? Stop being self conscious. Stop thinking the world has you under a microscope that they're grading you that they're judging you? And if they are, fuck them, you don't want them in your life? I'm sorry, I just probably said something that's not supposed to happen on a podcast. It's, it's, it's raw. It's real. Okay, but it's true. It's Yeah, absolutely. If someone is that kind of a human, you don't want them in your life. So what do you care what they think it's actually a good time to write them a little thank you note and say, you just saved me investing a whole bunch of time in the wrong direction. If you could just grow up fast enough on the inside to say, you know what, I'm going to be the truth of me, I'm going to be who I really am full on. And I'm not going to care because I'm going to win more friends that I'm going to make enemies. But at the end of the day, at the end of my life, will it have mattered, that some people had judgment of me that I never even knew about? I don't care. I just I really think that being proud of who you are, at least, and I don't mean in any sort of bragging, you know, not braggadocio, not not. You can be humble and proud at the same time. You can be kind at the same time, but if people liked themselves, and didn't give a wit about what other people thought, didn't give it so much weight, and would share their story, I find that most people, the vast majority of people. If you ask them about themselves, they'll tell you a story. And that story is mostly fiction. Because they've laden it with all kinds of stories that built up over the years, and they've swept a lot of the good under the rug, and they take themselves for granted. And it's it's not that what you're getting. If I ask if I asked other people tell me about someone. So that's nonfiction, I'm going to get the truth. They're going to tell me who they are, what the value of them is, you know, how they make them feel. They're going to tell me the stuff that matters. And I think that people hold themselves back as a result and they don't share their story as a result. And if they could just learn to be proud of who they are. Regardless, we all make mistakes. We've all got, you know, stories that Gosh, I'm embarrassed. I better be the first to share that story about me before someone else does whatever but I You know, like, growing up, a lot of it is about becoming the best version of yourself being okay with it, knowing everyday you can make your you know, you can strive to be better not than your competition or someone else but better than yourself. Right, a better version of yourself. I don't know, I just, I think I think that sort of, I'm not articulating it well, but that essential freedom to be who you are, and do what you what you care about. Behave toward people in a way that makes you sleep well at night. If you do those things. I think that's what a successful life looks like.

Alex Ferrari 1:10:45

Not and I love what you just said, not a successful career, but a successful life. And that's a very important distinction. So a lot of times, filmmakers and swimmers are so caught up into there. I'm only a screenwriter, I'm only a filmmaker. But at the end of the day, like, you know, you're also a human being your father, your wife, your wife, your husband, your a son or daughter, your other things besides your occupation. And that took me a long time to like when I was younger, I only identify myself as a filmmaker. And the moment that that didn't go well, in my life, my life was over. Because I gave so much power to these people I was meeting that could give me the you know, like, why aren't you Why aren't you opening the door for them? Don't you understand that this is who I am. Without this. I am nothing. And it took me years to figure out that like, Oh, I'm so much more than just a filmmaker. It's part of me, it's part of who I am. But it's so much. And that was a very, I just wanted to point that out. Because that's such an important lesson for people listening to understand is like you will not you are not, you're not what you do. You are who you are. And there's a very big difference in that you agree.

Gary Goldstein 1:11:55

1,000% You know, it's interesting, I had an amazing dad. He he was nothing if not a people person. And he had no filters at all. He wasn't a particularly he didn't he did he did. He did well in life. We weren't rich, but he you know, we weren't struggling. And but from history that he just he couldn't he literally didn't see someone station in life. He didn't see what car they drove, he didn't see much of anything about them other than and when you spoke with him, you felt like you were the only person that he was speaking to really truly he was like, you were special. And, you know, I think we you know, that's that's some of that's a bit generational and some of it's just individual and but I think that I lost my thread, there was something I've you said a minute ago, that I wanted to get back to,

Alex Ferrari 1:12:52

we'll come to me, if you're not who you are, but what not what you are, but what you are what you do, but who you are. Yeah,

Gary Goldstein 1:13:01

I mean, yes. I don't know. It's like, trust yourself. Share yourself with other people, you know, exactly. I, when I was when it when I was watching my dad, I guess the point I was trying to make is that, you know, there was a certain point that I recognized as I started to get out of my own, like when I went to college and beyond, right? That, gosh, what, what is what's the best part of this experience of being out in the world on my own. And the best part of it was meaning other people, you know, and like creating this sort of World of, and I at some point, I coined a phrase for myself, I coined a phrase, which is that whatever I'm doing, whatever I'm busy doing, really, the underlying mission statement here is harvest genius. So if you if, you know, like if I read a book by a great author, I wanted to track I want to stock that person. If I you know, like, if I went to a lab, and someone was speaking and they were impressed, I'm gonna, I'm gonna get in touch with them. I'm gonna walk up to the stage, I'm gonna get their number, I'm gonna do whatever it takes. Like, I didn't care about what walk of life they were in, I cared about whatever I thought was the best of humanity. Like I want good people in my life. So to this day, I've got tons of friends who have nothing whatsoever to do with film or television. And, and I think that I'm a lot richer for it. But it also keeps you a little bit balanced because Hollywood, there is that sort of almost vacuum that sucks you in a vortex, if you will, that sort of energy that says we are all consuming, we're inward facing. Like, I think you know that I won't tell who but there was a story years ago about a big big name producer who went on holiday and he went alone at a family but for some reason he was going on and he went somewhere and wherever he went when he And they didn't know who he was. And that vacation was supposed to be like a 10 day vacation that he was home in two days. And, and he because he could not bear that he didn't get reflected back to him who he was. Wow. Right. Like, how, how sad is that? Oh, I mean, this is a guy who would buy and sell companies who could, you know, he was like a big deal. But, you know, it's like, yeah, be be, you know, like, beyond plant yourself on terra firma and the terra firma isn't. It's not got the name Hollywood on it. Right? It's

Alex Ferrari 1:15:43

bigger than that. And like you and like you said, how sad it was for that producer. But there's a lot of sad. A lot of dead souls in this business, a lot of sense of who, you know, my wife is like, when we first got to LA, my wife refused after like, two or three of them. She's like, I can't go to any more parties with you. Because all people want to talk about is the business like, I want to I want to have a human conversation. I'm like, okay, we're in Hollywood. This is what we do here. And I was so excited. Because I was coming from Florida. I was like, I yes, I want to talk about the business all the time, because I never had a chance to do that before. And she's like, now, I wanted to have a human conversation with another human being. But everybody you meet is just all about, what Who are you? What can you do for me? And you see it and you see it at these parties do sometimes you're like, what do you do? Are you okay? You can't do it for me, and I'll walk away, and then walk away from you. And you're like, wow, like, you know, let's say if unless they see some sort of value. They don't even waste their time with you. Because they're hunting. They're like, they're like a wolf pack. Trying to find people to help them. It's just It's a sad, it's a sad way of doing things, but it's rather women. Now, last question, last question. Three of your favorite films of all time.

Gary Goldstein 1:16:56

Oh, my God. That's so unfair. People ask that question. So tough. Look, I grew up on the films of you know, the thing that made me fall in love and want to be down here with the films of the 70s. Right? Scorsese is a early Coppola, you know, I mean, on and on and on. I mean, it's like this kaleidoscope of, you know, Easy Rider and five easy pieces. But I also love the old films. I love the films like you know, Bo Garten McCall and Lauren Bacall, I love you know, like I come from to sort of timeframes. But I would say, I'm going to come up with some crazy like, probably once you want to, like I love the epic storytelling of David's lean. course. I loved the storytelling, a Sergio Leone fell. Did you know I mean, those are some of the guys that I would have to say, man. I don't know how you get from here to there.

Alex Ferrari 1:18:02

Like, once upon a time, in the West, once upon a time,

Gary Goldstein 1:18:07

once upon a time, and how did you know? Because once upon a time in the West was actually the film. I was with a bunch of buddies. I was at UC Berkeley, and one of my guys he was a poet and a long haired coupe called dude. And he said, Let's get out of here, I suppose finals next week. He said, Yeah, that's a good reason to leave. Let's go and we're going to hitchhike down to LA. Whatever the story was, it's like, Okay, fine. Let's go. So we went. Let's just say there might have been some illicit substances involved when when we were down there, Sophos? I know, and we decided in that condition that we were going to go to Disneyland because it was such a logical choice. And well, you know, the Disneyland had a lot of very large big boned crew cutted walkie talkie blue blazer, gentlemen. Who were the the guards of the castle. And they saw us coming a mile away. You know, our sandals, long hair hippie outfit, and like, clearly not, you know, entirely sober. And they wouldn't let us in. Well, long story short, what happened was we got we all pile into a car and go, bummer, man, you know. We take a and we're driving along and we see a movie theater we got That's it? We're gonna go see a movie. We sit in the front row high as a kite and staring up at this massive screen and what are we watching? Once upon a time with the West. I mean, that that that film is beyond genius. What's it certainly genius. I mean, what he was able to put but that's also said that first opening sequence. Yeah. The close ups of the cast.

Alex Ferrari 1:19:58

Yeah, you don't you there's no There's no dialogue for the first like eight minutes of the movie. And you're just like this. You're just sitting there like, Oh my god, it's just music and shot. And he's telling us the gun barrel with the fly. everyone listening after you're done with this podcast, please go watch once upon a time in the West, you won't be sorry. I mean, and then and then watch the rest of the man without men with no name trilogy. you'll, you'll enjoy.

Gary Goldstein 1:20:26

Man, you can watch the third man. The quiet man with john Florida marine O'Hara. Not bad.

Alex Ferrari 1:20:33

Not bad. Not bad. Not bad. Yeah, there's, I mean, I always asked that question, because, you know, I like putting my guests on the spot because everyone's like, Oh, come on. I can't I can't, I guess. But it's I always loved having these conversations, because we kind of go down different roads and like, and that's always fun. Because, you know, I always get, you know, the godfathers, obviously. And you know, there's Scorsese and Spielberg stuff. But then every once in a while, you get these kind of like, out of left field conversations. And once upon a time, there was obviously the message not been on has not in 600 episodes, not one of the ones that popped up all the time. It's not one of those automatics. But it should be because it's, it's just, it's just really, it's just really. Yeah, but bigger. It has been a pleasure talking to you, man. It has been a real honor. And I know we can keep going for at least another two or three hours. We could break the record, but I think we'll stop. We'll figure it out

Gary Goldstein 1:21:31

Alex, you're a total joy. I love Listen, I love what you're doing. And I love this conversation. And I know we've only just met but I hope to continue the conversation down the road.

Alex Ferrari 1:21:43

Absolutely . Thank you.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

Please subscribe and leave a rating or reviewby going to BPS Podcast

Want to advertise on this show? Visit Bulletproofscreenwriting.tv/Sponsors