Today on the show we have Emmanuel Oberg. Emmanuel is a screenwriter, author and script consultant with more than twenty years of experience in the Film and TV industry. After selling his first project to Warner Bros as a co-writer, he went on to be commissioned by StudioCanal and Gold Circle before writing solo for Working Title / Universal and Film4.

He has also designed an internationally acclaimed 3-day Advanced Development Workshop – based on the Story-Type Method® – which he delivers with passion to filmmakers all over the world. Emmanuel lives in the UK with his wife and their two daughters. His film agent is Rachel Holroyd at Casarotto in London. He is also the writer of Screenwriting Unchained: Reclaim Your Creative Freedom and Master Story Structure (With The Story-Type Method).

In Screenwriting Unchained, Emmanuel Oberg busts many myths and sets out an innovative method

This practical, no-nonsense guide leaves behind one-size-fits-all story theories and offers a modern approach to story structure, making it a precious resource for anyone involved creatively in the Film and TV industry (or aspiring to be): writers, directors, producers, development execs, showrunners and, more generally, storytellers keen to reach a wide audience at home and abroad.

Having identified three main story-types – plot-led, character-led, theme-led – Oberg reveals in a clear, conversational style how each of these impacts on the structure of any screenplay, and how we can use a single set of tools to develop any movie, from an independent crossover to a studio blockbuster.

This leads to a powerful yet flexible way to handle the script development process: the Story-Type Method®. A new framework that doesn’t tell you what to write and when, but focuses instead on why some tools and principles have stood the test of time and how to use them in the 21st century.

According to readers (see reviews below), Oberg’s new approach is a game-changer.

Here are some of the easy-to-understand concepts explored in Screenwriting Unchained that will help you improve any screenplay:

- How to identify the story-type of your project to make its development faster, easier and solve most story structure problems.

- How to leave behind the prescriptive, logistical three-act structure based on page numbers or minutes and replace it with a flexible, dramatic three-act structure that will help you design a rock-solid screenplay.

- How focusing on emotion, character development and managing information will allow you to go beyond the “protagonist-goal-obstacles-conflict” basic chain of drama.

- How to use the fractal aspect of structure to design not only the whole story but also its parts in order to avoid the dreaded “sagging middle” syndrome and breathe new life into your script.

- How to clarify what’s at stake and increase your chances of getting the project made with a new take on Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

- How to use subgoals to Sequence the Action and psychological/emotional steps to Sequence the Evolution of your characters.

- How to keep the audience engaged using tools like dramatic irony, surprise, mystery, and suspense, adding a third dimension to your story.

- How to master these tools and principles in scenes through practical exercises before using them in a short film, a feature film, a TV episode or a whole series following hands-on tips and advice.

- How to design an attention-grabbing opening and a satisfying ending.

- How to deal with hybrids and exceptions, as story structure isn’t about forcing all narratives into a single formulaic paradigm.

- The Rewrite Stuff: 12 Ways to a Stronger Screenplay, how to approach a new draft creatively and efficiently.

- How to make the difference between selling documents – used to raise development or production finance – and story design tools.

- Once you’ve developed a killer script, how to best pitch your project according to its story-type and get enthusiastic partners on board.

- …and much, much more!

Using many case studies including films as diverse as Gravity, Silver Linings Playbook, Crash, Billy Elliot, The Intouchables, Birdman, Alien, Groundhog Day, Misery, Edge of Tomorrow, The Secret in Their Eyes, Cloud Atlas, L.A. Confidential and The Lives of Others, Screenwriting Unchainedwill transform the way you write, read, pitch, design, assess and develop screenplays.

Enjoy my conversation with Emmanuel Oberg.

Right-click here to download the MP3

LINKS

- Emmanuel Oberg – Official Site

- Screenwriting Unchained: Reclaim Your Creative Freedom and Master Story Structure (With The Story-Type Method)

SPONSORS

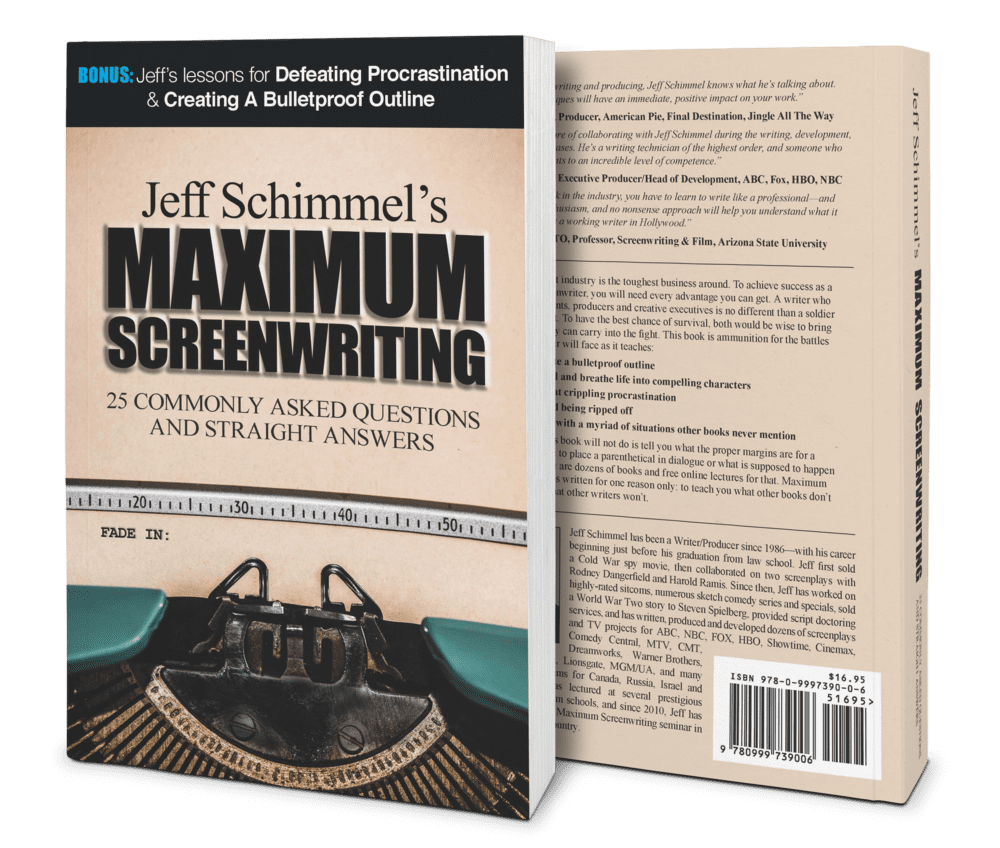

- Bulletproof Script Coverage – Get Your Screenplay Read by Hollywood Professionals

- Audible – Get a Free Screenwriting Audiobook

Alex Ferrari 0:37

I'd like to welcome the show Emmanuel Oberg. Thank you so much for coming on the show.

Emmanuel Oberg 3:01

Hi, Alex. It's, it's a pleasure. Thanks for having me

Alex Ferrari 3:04

know, thanks for taking the time out to hopefully drop some knowledge bombs on the on the tribe today. And I'm really interested to hear about your unique approach to story descriptive, screenwriting in general. And but before we get into that, how did you get into the business in the first place?

Emmanuel Oberg 3:21

Um, well, I, I think one of the best way to learn about screenwriting is to read and so I tried to find ways to read scripts and ideally scripts that were not produced, but had a good chance of getting produced. And so I started as a reader, I, I had followed a workshop a very informal workshop, led by a guy a screenwriter, who had been taught by Frank Daniel at Columbia University. And I just found a job as a reader for StudioCanal on us co productions, which is which was great because I've always loved mainstream American cinema but so the only thing I like, I have versatile days but but I have I'm very fond of with with a good American mainstream cinema so it was a really got a great opportunity for me to read scripts, which were very high level and and to do fairly good chance of getting made so what I find really interesting doing that was to try to make up my own mind before I saw the film and and then see whether I was completely off or whether I you know had had assessed properly you know, the, the qualities and potential problems of the story so I read hundreds of scripts of a few years and that was really really useful

Alex Ferrari 4:42

in very cool and in Where did you develop your method?

Emmanuel Oberg 4:49

Over the years? I, you know, it's always the same thing. I mean, you learn you read a lot you you learn a lot from other people, of course, when you start, and then over the years, I guess you do develop your, your own ways to look at things and I've always been interested in training because for me, the best way to learn is to, is to teach. That's the way the way I look at it, it forces you to clarify your ideas. And also you can see whether, what you, you know, what you come up with is kind of helpful or not. And so, I, I kind of, I did a lot of training over the years as I was, you know, working more and more as a consultant and then as a, as a writer or CO writer. And, and my, my training, gradually, I realized that my current my training was, there was more of a disconnect between what I was teaching or the way I was teaching and the way I was actually practicing screenwriting and, and I, I thought, I need to find a way to put that together. And that's how I decided, try to come up with my own my own theory or my own ways to my own way to put things together and try to make sense of it.

Alex Ferrari 5:59

Now, before we actually get into your method, what after reading so many scripts, I always love asking this of readers and also of screenwriting instructors, is what is the biggest mistake you see first time screenwriters make?

Emmanuel Oberg 6:14

Oh, it's, it's, you see some very, very common problems in in in beginners, screenwriting is screenplays, but I guess the one of the I mean, one of the one of the biggest one I guess is to is to try to write a script without thinking about the way it's going to be read, or been read by someone who has never read it or seen by the audience for the first time. Very often when we write a screenplay, especially when we begin we can be really excited and, and focusing on our protagonist, for example, and see the story from the point of view of the protagonist and exclusively from that point of view, and, and many problems in screenwriting come from that. Because Because sometimes, if you have an antagonist, they're not clever enough, because you're not thinking okay, if I am the antagonist, what would I do in this situation? And, and, you know, things, things like that, I think it's really useful to try to, to think about How will an audience or how will a reader who has never heard anything about my story? How are they going to perceive the story, how we, someone who doesn't know anything about the story is going to perceive it. Because we know if we, I mean, we supposed to know everything about our screenplay. And sometimes we will lose sight of that we don't realize that there is a mystery that we find fascinating, but that's because we know the ending is in the end, but the audience won't. And the audience might be very bored after a while, just because we don't know enough. For example, all these things I think is make, you know, can explain quite a few mistakes in beginner screenplays sticking to a point of view, and not realizing that the audience doesn't know anything and, and might need to know more than than we think they might need, at some point.

Alex Ferrari 7:59

Would you agree that a lot of screenwriters first time or not first time, a lot of times they'll try to get ahead of the marketplace and try to write what's hot right now as opposed to writing what is something that's inside of them? And generally, it rarely works that they

Emmanuel Oberg 8:16

do. I mean, you asked for one, so I tried to pick one. Oh, no, there's probably 1000. Of course, that's give me another one. I mean, it's are you still here? Yeah, I'm sure. Yeah. Yeah. Okay. No, the screen just went? Well, yeah, no, I am. i It's, it's, it's a it's a big issue. Because of course, if you do that, you'll you'll three, four or five years late. Because what's what's hot now was in development three or five years ago. And, and it's just, it's just if you if you do that, you you tend to be out of sync of what, what's actually hot at the moment. The other thing, I think that's wrong when you do that, in that you're you're trying to write what you think the market want. Once what I think you should write what you feel passionate about and really want to write, of course, it has to match. You know, it has to be something that can be that can get made, and that's realistic, and that has an audience and so on. But I think the main thing to be concerned about is, if that's my last screenplay, what do I want to write and not trying to think, Oh, I'm going to write this because that seems to be really hard. And that seems to be what they want. And most, you know, most, most people working in development, they don't know what they want. They want a great screenplay. They will see it when they when they find it on the desk. But although they will save you as demo on this and anyone that and very often they do have brief regarding specific jobs or specific kinds of stories. But regarding beginning you know, where they actually won't. Very often it's like, you know, they find something they like, because it's because it's exciting because it's new because it's original and for me the best advice to to follow when you're writing screenplays to keep that passion keep that Keep what you know, write about something that you're really excited about. Because if you're not no one is going to be it's just, it's just people sense it when when they read a script where the writer has just tried to follow a kind of formula or try to second guess the market, it's just feels either formulaic, or, or, or, you know, it's just not interesting half the time.

Alex Ferrari 10:21

Yeah. And generally speaking films that do kind of explode or go out, you know, that are a little bit different than the norm, are the ones that make it are because the writer and or filmmaker was extremely passionate about what they were doing. And they had a very unique voice. You know, I always use Tarantino as an example. Or Nolan, or, you know, or Sorkin or these guys.

Emmanuel Oberg 10:44

And as you as you can see, these guys, they can be very original, but that doesn't mean they cannot reach a wider audience. I mean, whether it's mainstream or isn't necessarily blockbuster audience, but it's, it's an audience that's definitely big enough to, to recoup the investment in their project. And I think it's, it's, it's, it's not incompatible to write something you feel passionate about, but doing doing it in a way that's that allows you to not, you know, not, you know, reaching an audience and writing something original is not incompatible.

Alex Ferrari 11:18

Now, let's talk a little bit about the story type method, which is the method that you have, yes, let's that you've developed, I'm very interesting to see what this method is. So please tell the audience what this is.

Emmanuel Oberg 11:32

Well, it's, I mean, I guess at first it's, it's, it's a kind of reaction. I'm a screenwriter, so I'd rather write screenplays than write books about screenwriting. But I, I just felt over the years again, I felt frustrated with a lot of of screenwriting theories floating around which I found were quite prescriptive in the way they try to tell you, you have to do this, you have to do that. And that page number is, this is supposed to happen. And I just couldn't find any real justification for that. And some of them are very useful from a kind of productivity point of view, they tell you, Well, you should follow these steps. So if you do this, this and that you have a screenplay. And that's true. If you if you follow these, this, this kind of formula, or that kind of way to come up with the story, you will end up with a screenplay and you know, it will have 100 110 billion pages, and it will tell a story. And the problem is, is that when you when you write a story that way, and you tend to end up with a story that's quite predictable. And you also tend to be much less free in the way you want to tell that story. And, and I was looking around, I was watching films around. And and many of the films that I was watching, you mentioned Christopher Nolan, for example, I'm a big fan of Christopher Nolan. And, and when I watched his films, I don't see any kind of, you know, formula that's being applied. Absolutely. Not dating, they're moving. They work. And, and so what I tried to do that I tried to find a way to approach screenwriting, you know, in in such a way that you would structure your story, but you would be much freer in the way you would approach story structure. That's that's the main motivation for the method. It's not I don't believe I'm right, I don't think there is one way to look at a story structure. I think that as many ways as there are writers, but I wanted to try to come up with a tool that would try to focus on what's what's what's been useful over the years, the kind of the tools and the principles that have been useful without without being prescriptive into the way to use them. I find that approach more, it's something that suits me better, I guess. So then

Alex Ferrari 13:46

what is specifically the story type method?

Emmanuel Oberg 13:50

Well, the the idea that I were the first thing is that I, I just disagreed with the fact that we could, we could apply the same method or the same way to structure a story to old stories. So I try to think okay, if we, if we if you try to be more useful than saying you can do anything you want, because I know rules. I try to think, okay, how can we define what a good story is? And, and I came up with a, you know, with my definition of a good story for a screenplay, which is a metaphor for problem solving process. And that, that, that way to define a story It doesn't it doesn't talk about threat structure, it doesn't talk about anything like that. It's just what is the story? It's it's a metaphor for problem solving process. So we that that means that in any story, which we can follow, there tends to be a main problem, that story that's that's the, that's the focus of the story. And what I find useful as the next step is trying to eat to try to identify where that problem lies in the story. Because I, I find that depending on where the problem lies in the story, You tend to develop it in a slightly different way, you can use the same tools, but you will develop it in this in a slightly different way. For example, if the main preliminary story lies outside of the protagonist, we tend to deal with what I call a plot lead story, which is a story where, which focuses on the main dramatic action, someone wants to achieve a goal, usually a conscious goal. And, you know, it's the kind of it's the most classical form of storytelling. They meet upcycle, they experience conflict, and we tend to identify with with that character because of that. And that, it's, it's kind of, it's a very important part of storytelling, but it's not the only way to tell the story. The second possible location of the problem is when the problem lies within the main problem lies within the protagonist. And in that case, we tend to be dealing with what I call a character lead story, where the the main source of conflict in the story comes from the protagonist themselves. And in that case, what what shapes the story is the main evolution of the protagonist, not the main dramatic action,

Alex Ferrari 16:10

it was it was an example of that.

Emmanuel Oberg 16:13

What it Takes take two fairly recent examples, or if an example for plot lead story, if you take gravity you know, it's surviving, coming back, you know, going back to Earth, that's the main problem lies outside of the protagonist, it's, its space, how to you know how to survive in space, it's like in many disaster movies, where it's, you fight the natural, you know, an antagonist, which is, which is nature, force, which is nature. So the main problem lies outside of the protagonist, there is an internal subplot which is about the death of the daughter, for example. But the main problem, I guess we'll agree on that is that she has to survive, and she has to find a way to get back to Earth. That's the main problem in the story. So it's blood led, because the main problem lies outside. If you take a story like Silver Linings Playbook, that's character in it. He has a goal, he has a very clear conscious goal, which is to get back with this, get back together with his wife, Nikki. And we understand, we understand that goal from minute one in the story. But as soon as we realize that he's actually in a psychiatric hospital, you're kind of forget, hang on, I understand that you want to get back together with your wife. But until I understand why you are centered, that psychiatric hospital, I'm not sure that I want to be with you on that journey. They will be with your wife, you know, so you spend the first 10 to 15 minutes of the film trying to figure out what happened to this character. And why was in psychiatric hospital. And by the end of the first 15 minutes, you I think you understand that, yes, he has a conscious goal as a protagonist, he wants to get back together with his wife. And that's what he's going to try to achieve the muscle the film. But I think the audience understand why telling the story that what he needs, is to move on from his wife. And we actually don't want him to end up with this way. But we want him to end up with Tiffany, who is going to meet a bit later in the story. So we we understand that what's at stake, though what's really at stake in the story is not what the character wants, but where the character needs. And that the main problem in the story actually lies within the protagonist within the within bat, in his example, because he is deluded in a way, he thinks that is fine, that is in control that, that he will get back together with his wife, because he has a positive attitude. And he's, you know, all about finding the silver lining. In reality, we know that Ti is not in control that you need to move on. But you need to it needs to get better. And in that way we have we have an advantage over him. We know more than he does, we feel a bit clever in a way because we we think that we we are more aware of what he needs that he is than he is himself. And for me, that's a character lead story. It's it's when the protagonist might have a goal. But actually, what they need to realize is that they have a more important problem within it within themselves that they need to solve. And very often this problem isn't, then they're not aware of that problem. And in incorrectly so one of the one of the very interesting things about character lead stories and why I think it's interesting to make that difference between, for example, plotline and character lead, is that very often in character lead stories in order to get what they need, the protagonist needs to give up on what they want. Which is, for example, what happens in Silver Linings Playbook, he wants to get back together with his wife, but in order to move on and to end up with the woman that he actually shoots with, he has to give up getting back together with her. And that's his journey that's this is arc to use a kind of, you know, well known concept in the story. So that's an example of from your Have a character that story where the what what shapes the story is not the main dramatic action of what the character wants? But is the main evolution of the character? How is the character going to evolve? Another way to talk about the differences, say in a blood lead story, when the main problem is lies outside of the protagonist? The well most of the conflict tends to come from other characters from outside of the character. But you, you, your your the question that you're going to ask yourself is, will the protagonist of a most of the film is will the protagonist reach the goal or not? What we want to find out is, are they going to be able to survive or to kill the bad guy or to whatever? While character's story, the question we ask ourselves is not will the character get what they want, but will the character find a way to change or not. And because of that, we we will develop will structure the story actually quite differently.

Because Because on the one hand, when you develop a plotline story, you you can you can stick to a single goal over the whole film, you'll have sub goals, different ways for the protagonist to reach the goal, but you can really shape the story. And use as a dramatic backbone, the main main dramatic action of the protagonist of other countries, one of the protagonist, in a, in a character lead story, what you're going to do is a bit different because because you're focusing structurally on the evolution of the character, what you're going to do is you're going to try to generate the conflict in the story that's going to force the character to change. Because that's usually when we change in life is not because we've decided to change but it's because things happen that, that that force us to change, and that tends to be conflict, which is also you know, how, how one of the reasons why confidence is so important in in screenwriting not not, because we're told we have to have conflict in a story. Because if we every time, we want change, or we want evolution in, in a story that tends to happen because of conflict. So so that's that's, that's one of the of the of the biggest differences because between bloodline and character, land

Alex Ferrari 22:14

have a theme and have a theme lead. Well, theme that

Emmanuel Oberg 22:17

is, is is less common, especially in in cinema, I think it's more common in TV, writing, and possibly in documentary. But similar is when, when you will, sometimes you you don't have a main plot in a story. In a product story, the main plot is about the main dramatic action in in a character's story, the main plot is about the main Dramatic Evolution. But sometimes you don't have that kind of main dramatic action or main Dometic evolution, you have different storylines, which are connected with each other. And you cannot really say this one is the main one. And usually what we can usually call this multi stranded narrative. And what tends to happen in these kinds of stories is that the main problem is, is license society. And so all these different storylines, if I take an example, theme, like crash or Magnolia, or even a thing like Dunkirk, another Christopher Nolan film, and when they have these different storylines, which are connected to the same theme, and it can be very interesting story form, because sometimes we handle we try to handle a problem, as as I said, which is in society. And it's very difficult to, to handle that problem in such a way that we can come to a conclusive ending, because it can feel very black and white, to say, yes, pregnant solves the problem, or not the protagonist fails to solve the problem. Because if, if, for example, we're talking about, let's say, drugs, as in traffic, so that x traffic, whether the main problem is in society, it's about drugs, and that how it can threaten you know, Western societies and, and, in, in a story such as this, if you take a single protagonist, okay, you can decide my protagonist will, will, will, will solve that problem will fail. But that doesn't say much about the problem in society because when individual resolving or failing to resolve the problem, you know, doesn't mean much What if you if you handle this such a story, as a theme, that story, you can because you have, I don't know 578 10 different storylines, each of them we need some protagonist and all of them connected to the same problem in in society, then you can have a much more subtle way to approach this the problem that is that you want to, to explore because you can have some of the protagonist of of each strand, succeeding to find a way to deal with the problem others who would fail, and in the end, you don't have to say yes, they they succeed, or yes, they fail, some will succeed, some will fail, and you can still convey some meaning Because we'll understand that problem in society better, we'll think about it after we watch the film and so on. So for me, it's one good way to try to avoid the, the the first, an open ending when it's frustrating. Sometime an open ending can be very satisfying, because you're like, oh, you know what happens and every, every person in the audience can make their own ending

Alex Ferrari 25:21

in a way, kind of like Inception if we might use another conception. Exactly. Inception,

Emmanuel Oberg 25:25

Birdman, there are themes that work with an open ending. Even Thelma and Louise is kind of

Alex Ferrari 25:32

certainly kind of kind of ending. You know,

Emmanuel Oberg 25:35

we kind of know that that guy is not going to stay suspended mid air forever,

Alex Ferrari 25:40

that would be great.

Emmanuel Oberg 25:43

But those that it doesn't show, no,

Alex Ferrari 25:44

let me ask you a question about Thelma Louise, is it I would imagine that's a character led a character led story Correct? Or am I wrong?

Emmanuel Oberg 25:54

It's a it's a very interesting case. Because actually, it's, it's it's one of these of the situations where, and what actually one of the reasons why I didn't stick to solely these three main stereotypes, is because I, you know, I guess three is better than one. But I still don't believe that you can fit all stories in three boxes. So like, it was a fourth box, which is something else, you know, hybrid thing that don't fit into any of these boxes. What I find interesting in the manner is I've not really watched it recently. But what I find interesting in it is that I, one of my frustrations, I love the film, and I really enjoyed watching it, but one of my frustrations in it was that I'm a feminist. And I felt quite frustrated with the fact that two women who wanted to be free, who had not really done anything wrong, I mean, okay, they kill the man, but that's the guy who was trying to rape one of them. So, you know, it's not it's not as if they had, you know, decided to, to murder the guy.

Alex Ferrari 26:56

No, it was it was done. It was done in the heat of the moment. Self Defense,

Emmanuel Oberg 26:59

and the guy was a start. So I was like, okay, these these women, yes, they've committed a crime, but they just wanted to be free. And the way they pay their aspiration for freedom is death, as if there was no way

Alex Ferrari 27:14

to the ultimate, the ultimate freedom.

Emmanuel Oberg 27:18

And from my point of view, as a feminist, that's the only thing that I didn't, I really enjoyed the whole film. But I didn't like the ending, because for me, it is, it's mostly plot lead. Or it could be theme lead, it's not multi stranded, but it could be seamless, because the main problem in that film is not really in them. It's in society, or it's in other characters, but it's not in them. And the fact that they have to show that they die in the end, because they exercise their freedom. And it looks like it's the only way out. It makes it a very memorable, memorable ending, because we didn't, we don't want that. And we don't really see it coming. But it's from a kind of theoretical point of view. It kind of always, as a feminist, it kind of always slightly annoyed me that these women that I that I loved, had to die, I guess, makes the tragedy. And

Alex Ferrari 28:05

by the way, if no one's seen some of Louise we're sorry. Euler? No, no, no. spoiler, spoiler alert.

Emmanuel Oberg 28:12

You have you have to see it now.

Alex Ferrari 28:15

If you haven't seen it, it came out and what 8990 I think it's the spoiler alert pot, it's past. It's your fault at this point.

Emmanuel Oberg 28:24

In the recording 10 minutes, if you can.

Alex Ferrari 28:28

Now, um, let me ask you, so how do you like identify the story type of your project, cuz I just made it See, I thought it was character driven, because those characters were so strong. But further And, you know, the further we analyze it, it was like, No, you're absolutely right. It's not a character. It's not something within them.

Emmanuel Oberg 28:45

I know. But, you know, what you just said is such essential, it's, you, you put your finger on it, it's very often we talk about character driven because we have strong characters. And and that's that's not what I mean by character lead. And maybe it's not different or distinctive enough, but one of the reasons why they didn't say character driven but character led was to try to find a way to to not say character driven. Because for me, a great story has great characters, whether it's blood lead, character, lead or theme lead or or anything, if we don't care about the characters, we, I think we simply won't care about the story. And it's true in a comedy. It's true in a thriller, it's true, you know, you can you can have your characters face a lot of conflict, a lot of difficult situations, if you don't care about them, if you don't understand them, if you don't understand the decisions. You know, we just don't care and and, and what when you said it's, it's it has strong characters, but it's not character driven, because it's not character led, because the main point is that within the characters, and that's, that's the key to the method that I'm I'm trying to suggest is to try to, to go away from okay, it's a lot about the plot or it's character driven, but but to try to really identify ways the main problem in the story and you will see that in some stories we have story which has really strong characters, but is nevertheless blood LED or, or something else. It's it's definitely not correctly connected.

Alex Ferrari 30:12

We'll be right back after a word from our sponsor and now back to the show you know, there's an I always love beating up on this film because it deserves to be beaten up. Justice League A Film A film that had which one sorry I did Justice Justice League the the Justice League movie they can't forget Justice League movie though, which was considered a horrible horrible film and I saw it as a horrible horrible film.

Emmanuel Oberg 30:45

Which many it is because I probably have seen it but

Alex Ferrari 30:47

no, it's the one was it's the one with so much like each other. which one it is? No, it's the one that has the Superman in the Batman. It's the one right after Batman vs. Yeah, and it has Wonder Woman in it and it has Aqua Man and all this stuff.

Emmanuel Oberg 31:02

I confuse it with the with the with the Batman Lego Movie.

Alex Ferrari 31:06

By the way, much better film.

Emmanuel Oberg 31:10

I mean, I have seen it so we can talk about okay,

Alex Ferrari 31:12

so that film. You know, what I find fascinating is that all the characters in the movie are extremely well known by the public and has major emotional connections to those characters like Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman. And, and yet, it failed miserably on multiple levels to connect with audiences. Now there was a lot of things happening to the characters. But at the end of the day you really didn't care about I didn't at least I didn't care about that Batman or that Superman or that Wonder Woman. And we hadn't yet I don't think we had a yet seen Wonder Woman the movie I don't think had come out though she was introduced there yet. Yeah, it was or if she had it, you know, she was the only good thing about it. But then oppo man hadn't come out yet. So we hadn't really connected with that character either. As opposed to Nolan's Batman, who no, sorry, I'm

Emmanuel Oberg 32:05

saying I'm making a fusion with Batman vs. Superman. in Justice League sheet. I think it was after

Alex Ferrari 32:11

it was after your right it was after she was like one of the things that you did connect to her. Exactly, exactly. But you didn't connect to Superman, or Ben Affleck's Batman that nearly as much as like you would connect to Chris Nolan's Batman, like that Batman is yes,

Emmanuel Oberg 32:26

but but that I mean, that that's also a very interesting point, which is, which is all about conflict in In fact, it's an it's a big problem that you have with superhero movies. Because if a superhero doesn't have doesn't experience enough conflict, when well, then of course, what the boring? And what what works with when you take a single whether it's Batman, or Wonder Woman or Superman, if you take the single movie, usually, you try to find some ways in that single movie to make it so that, yes, they have a superpower. But either, you know, but Superman has kryptonite, and Batman has dual identity and what his main problem in one in in Batman Begins, he has to find redemption.

Alex Ferrari 33:12

Redemption is fairly a symptom

Emmanuel Oberg 33:15

of conflict because that if you know he probably feels responsible for the death of his dad and his parents center and all of that. And so you feel for the characters because they do experience a lot of conflict despite the despite that the best superpowers? And also what tends to work well in the first. I mean, the Dark Knight was fantastic. No, but probably at least as much because of the Joker then because of as a character then then because of the Batman instead. But in Batman Begins, you you feel a lot for the character. And also because that it's the construction of the person who's going to become Are you still origin? When I was talking about the Batman Begins? Yes. Yeah, it is the origin. Yeah, you're right, sorry. And so and so there is a dramatic irony because we know that this character is going to become Batman, or is going to become Superman. And so we're interested to finding out how that's going to happen, which is one element of interest in the in the story when it's about one individual superhero, but also, you if you find ways to get humans to understand how this character is a human because of the conflict that they experienced and the emotions that they experience. The superpowers are just one element of the story, which can make some action sequences and set pieces really exciting because of what happens in there. But we do care about the character. And so we do care about the action sequences in the set pieces. If you don't have that, you're in trouble and I think that's what happens in these films where you have you know, the ensemble piece without being properly structured as as, as as a story in itself, like if you take the Justice League, yet they have to save the world But Again,

then that's the thing, but you don't I can't remember what is the main conflict? I mean, the some of them will,

Alex Ferrari 35:07

there is there is none. Like there's like there's, they're they're trying, I think they're trying to create a conflict within the team because they're not really a team, because they're all these huge, you know, they're essentially gods. So you're like having a bunch of Gods fight against each other, like amongst each other. And then the outside force, which is we've seen a million times doesn't really pose a tremendous amount of it does pose a threat to the world, but it doesn't pose a threat. I just, like someone like this, something as simple as the Joker, who arguably is one of the greatest villains I've ever seen on screen that the Heath Ledger Joker, because he he's literally counterbalance to Batman. He's the opposite. You know, you know, it's he's completely opposite in every which way to, to Batman. And he challenges Batman in a way that, you know, it scars him at the end, you know, at the end of that movie, he has to make a choice. You know, that leads us into the Dark Knight Rises. But based on what challenges that character that that villain did to Batman, and that is what makes that movie and it's not a huge, like, the stakes aren't. They're huge, to a certain extent. But they're not like the world's going to end it was much more personal. Like, yeah, we're going to blow up the city. I'm going to blow up a boat, or I'm going to take your girl, those are very small things compared to Well, yeah,

Emmanuel Oberg 36:30

but I mean, well, it's very, very clever. It's from a thematic point of view. Yeah, I think it has a very strong theme, which is, you know, chaos versus order. Yes. Yes. And what's what's really interesting, also, one of the main questions it raises, which I think make the makes the film very interesting thematically is, is it worth it for Batman to risk his life and to fight for Gotham City's people? Yeah. And that's really well illustrated in the, you know, when the two boats and the and the bombs and are they going to make the right decision and these kind of moments in the story that they they're, they're full of suspense, but it's also they're also very interesting thematically, and I think one of the greatest thing about about the Dark Knight is that you established the protagonist in, in, in Batman Begins, and in Batman Begins. As it happens, the protagonist is also the main character is the character we are the most interested in. He's the character who experiences the most conflict. So he's his protagonist, and main character in The Dark Knight. What's really interesting is that Batman and God on I guess, our protagonist, protagonist, but but the Joker is the main character. Oh, absolutely. And that's what makes this story fascinating as well. That is, is a fantastic antagonist is I mean, Heath Ledger was was was remarkable in the past, but but we we have a protagonist in Batman and or CO protagonist with Batman and Gordon who are moving the story forward. And yes, we want them to succeed, and we feel for them because of the conflict and so on. It's full of surprises as well, which, which makes the story very interesting. It's very well written. But the, the conflict with I mean, the the most interesting character, I would say, was Batman in Batman Begins, but in The Dark Knight, the most interesting character is, is the Joker question without question very often the case in in monster, you know, in horror films, in Monster stories, you have protagonist that we identify, we want them to survive, we want them to succeed, we become them during the film at an emotional point of view. But the most fascinating character, the most interesting character, it tends to be the antagonist in these industries when they work that that and I think that's, that's the way the data the Dark Knight works with a really good protagonist antagonist situation.

Alex Ferrari 38:45

Yeah, and the thing is that we spend so much time with the villain, like you generally don't spend so much time with a villain in a movie, you see them come in and out, and they, they twirl their moustache a little bit, you know, but

Emmanuel Oberg 38:58

that's, that's when the movies is boring, correct? Correct. It's, it's when it becomes predictable. I mean, saving the world is the most, you know, cliche, goal that you can give an antagonist. So sometimes it can, it can be, it can make an interesting film, but you need other things to make it interesting. If it's just about a bunch of superheroes get together to set the world it.

Alex Ferrari 39:22

It falls flat, as falls flat. And the thing I also love about the character of the Joker is that his unpredictability is what keeps you on the edge of your seat because you really have no idea what he's going to do from moment to moment.

Emmanuel Oberg 39:37

But that's, that's also what happens when you have a really good match between the strength of the protagonist and the strength of the antagonist. That's when superhero movies become boring. It's when we we know that they're so strong that actually we can answer that we know the answer to the movie before the end with a dark knight who actually we don't know the answer to the movie until the end and even the end manages to surprise us. Absolutely. So that's that's that's one of the The things in a way, and that's, that's something that you that's really important to, to understand when we write a screenplay is that, yes, conflict is important, but you only, you only generate conflict through the difference between the strength of the protagonist and the strength of the obstacles that they face. And when you have a really strong protagonist, as in a superhero movie, where you either need to find an antagonist who is at least as strong, and sometimes even look stronger. I'm thinking about some some scenes, for example, in, in, in Boone supremacy where Boone is fighting one of the other agents who was trained just like him. And you're like, yeah, that works, because we know that they had the same training. So when they fight, you feel conflict for bone because he's fighting someone else who is who has had the same training and is just as strong as him. And you need to do that when you have strong protagonists, you need to find ways to make them face some characters or situations which actually generate conflict, because otherwise just have a kind of conceptual antagonist. But if they're weaker, they're not original. Or if they don't generate obstacles that we're not expecting. Well, then it's just, it's just boring. It's too predictable. And it feels easy. Yeah. And

Alex Ferrari 41:15

I think that is one of the big mistakes a lot of screenwriters make when they're writing their antagonist is that they're, they're weak, they're weak. They don't they don't they don't do exactly what you just said. They have to be as powerful, if not just a bit more either. If it's not as strong, they have to be extremely much smarter or something along those lines. That's why Lex Luthor versus Superman to a certain extent now it's so boring to watch.

Emmanuel Oberg 41:40

It's a bit outdated, but at the time watching, but if you're not watching it, the first one, the first one, yeah, yeah, the first one. Yeah, I'm that old.

Alex Ferrari 41:50

I am that old, too. I saw it too. I saw it at school, it was great. But that was like the now and like it, I don't want to keep going on this superhero kick, I apologize. But I find it fascinating because it's something that a lot of us can kind of connect to. And it's a good illustration of what we're trying to say, oh, what you're trying to say with with your method is, if you look like a movie like Superman to where he's fighting, three super people. At the same time, one extremely smart, one's extremely strong, much stronger. And one's a lot more cunning. He's literally fighting three, very top and antagonist. And that movie, it was so brilliant, because it wasn't just Three versus one. He was suffering. Like he was dealing with things internally where he gave up his powers to be with the woman he loved and, and then like, oh my god, what am I gonna do? I can't find this all this kind of drama that went around with it was so brilliant for I mean, for its time, it's, it's absolutely stunning. Would you would you agree?

Emmanuel Oberg 42:55

I would agree. I'm not going to agree too much only because I don't have a very, you know, vivid memory of it. I've seen it. Yeah. But I, I don't have a memory of it as strong as I have for the darkness. Sample. Gotcha. But I agree with what you just said. I mean, it's, it's it's one of the things that that made it work the fact that you you have three strong antagonists.

Alex Ferrari 43:20

Now I wanted to I wanted to talk a little bit about Maslow's hierarchy of needs, which is something that you have in your book, how can you incorporate Maslow first of all, explain to the audience that they don't know, what is Maslow's hierarchy of needs? And it also how can you incorporate that into the writing? Well,

Emmanuel Oberg 43:37

Maslow, I mean, Maslow was a psychologist, a Russian, I think psychology is from the 1940s. And he came up with this theory, which was at the time quite groundbreaking in psychology called the key of needs. And you need in this theory, what he did was breaking down human needs into five different layers or categories, from the most basic ones that absolutely every single human beings go through and can relate to and understand, which is about remaining alive. It's the physiological layer. And it's usually represented in a pyramid with the with the the layer, the base of the pyramid being the one that most people can relate to. So that that first layer is physiological so it's about breathing. It's about food. It's about water. Sex not not as in having sex but as in if if as a species we don't have sex this species dies sleep homeostasis, which is the you know, keeping your the integrity of your body to make sure that you don't lose blood or don't lose up a normal fruit. Don't get any wound, you know, physical wounds, expression, which, which is a very basic human need, but if you you know, it can be trouble if you cannot fulfill it in Yes. So these this kind of first layer, it's, it's, it's true for, you know, every human being will relate to that because if you're a human being you, you need to fulfill these basic needs to stay alive. And as you go up the pyramid, you have different layers. So, safety is very, a very important layer, which is about security of body of employment, resources, morality, family, property, all the things you need to have to once you're alive physically, how can you stay alive, so you need a buddy have a roof over your head, you need to have a job to keep, you know, being able to pay your rent or feed your family and so on. So that's safety, which is very, again, understood by almost everyone on the planet. And then you have a board that a third layer, that equals love of belonging, which is about friendship, family, sexual intimacy. And above that, is team which is about confidence, achievement, respect of others, or by others. And the the layer, the very top of the pyramid, which, according to Maslow, you can only relate to if you found a way to fulfill all the other levels, which we could discuss. But it's self actualization, which is all about morality, creativity, spontaneity, problem solving, lack of prejudice, acceptance of facts, which are quite conceptual things. And that's why they are at the top of the pyramid, the idea is that through life, you go from focusing primarily on physiological, and then you grow through the pyramid. So you then become more attuned to safety than love belonging. And the idea from investor's point of view is that as you as you fulfill one level, you can start focusing on the next one. So and, and it's true that it's very, very difficult, for example, to focus on self actualization, when everything else in your life is, well, usually, if your life is in danger, you focus just on staying alive, I think. You know, if you lose your job, or if you, if your house gets destroyed, you know, something as basic as that, it must supersede everything else like your, you know, again, once you physically safe, the next thing that you need is protection from from the cold and from from, you know, lack of money and stuff like that. So if you have problems at lower layers of the of the pyramid, it's quite difficult to concentrate on the on the layers above it. And, for example, we know that if we lose our job, or things can happen in life, that can make relationships, for example, more difficult, because we might not have the time to dedicate to them because we dedicated more time to what's going wrong in other parts of our lives and stuff like that. So

the original Maslow theory is, is this idea that you have a different hierarchy in human needs, and that some of them are much more universal than others. And that you tend to be able to focus or to relate to the ones at the top of the pyramid, once you fulfilled the ones before. And I've always been fascinated with that, with that theory, because I, it kind of it felt to in many ways, I think, from a psychological point of view. I mean, in the psychology field, it's been superseded by the other theories seen. So I don't think it's seen as accurate in in that field. But it, it kind of took to me and I thought there is a way to use this in screenwriting, and one of the first one of the most useful ways I found was to think okay, if we agree with the idea that a story, good story is a metaphor for problem solving process, and that we have one main problem in in every stories. How, where would you place that problem in the pyramid? That main problem in the pyramid? Because I think that can tell you a lot regarding the audience regarding the show of the film, even its story type and, and other things like that. So for example, if you take we use gravity as an example. Yeah, so let's stick to that. If the gravity it's a to just a movie to thriller. And the main problem in in gravity, I think we'll agree is about survival, right. As another space station is hit, she's trying to survive with Kovaleski to start with and then on her own, but the main problem is, how is she going to survive and find a way to get back to Earth and this survival is at the very bottom of the Batman problem is at the very bottom of the pyramid. It's about breathing because in space if Something goes very wrong, you can breathe. And it's about homeostasis. How do you keep your the integrity of your body? I mean, that's that's what she's trying to protect and to, to address in gravity primarily. And one of the, one of the the interesting things when you when you think about that is that when the main problem in your story is, lies, at the very bottom of Maslow's pyramid, what it means is that the potential audience for the film is the widest possible audience, because every single human being on the planet can relate to that problem, because they can understand that problem of survival. Okay. And what's also very interesting that because it's the first layer of the pyramid, and because it's about every single human being on the planet, it doesn't matter that you know, which language which culture, normally the protagonist is from, but the members of the audience are from because they share that problem. It's a problem that affects every single human being. And, and I think that when you start looking at the method that I'm suggesting, in that way, what is the main problem in the story? And where does it lie in Maslow, it can, you can get a lot of benefit from that. Because you can get a sense of the potential audience you don't, it's not going to tell you whether you will have a bigger audience or not. Because if your script is bad, it's bad. Fair enough. And even a bad script doesn't mean that you can get a wider audience anyway. But what it can give you an indication of, of the potential audience of the film, if you don't, if you're not aware of it, and if you don't do something about it, take an example at the opposite side of that. If you if you think about a story, like crash, for example, which is the main point in the story is racism in LA, okay, it's how how, how are people in LA? CO, you know, dealing with with the problem of racism in society, in society, it's a problem in society. And that's one of the reasons why triggers what I call a theme that story and multi story narrative. So you have like 810, whatever different depending on the way you you count strands and in crash, you, you won't come up with the same number, but that doesn't really matter. What matters is that you have different strands in the story, which are connected to the same theme of, you know, racial tension in LA.

And if you think about that, that problem is, is sits right at the top of the pyramid, because it's about morality, it's about lack of prejudice, acceptance of facts. And the main problem in the story, the one that sits in society lies at the very top of the pyramid. But if you look at each strand in the so you could think, okay, because it's at the top, then it has a very limited audience, because very few people are going to be able to relate to, to this, despite the fact that thematically it's appalling that that everyone can relate to. But what happens is that in the way the story is designed, although the main problem lies at the top of the pyramid, if you look at each strand, it the problem in each strand in that story actually lies much lower in the pyramid. It's not about you know, solving racism or it's not about lack of prejudice. Very often, the main problem is about protecting your family protecting your business. You know, if you think about the locksmith, for example, in in Crash is trying to protect his family, the person shop owner is trying to protect his business. At some point, it's even going to be about survival when when one of these characters is going to have his life in danger. And because the main problem in his strand lies lower in the pyramid that widens the potential of the audience of the story. And that's, that's, that's one of the things that can that can make a difference between two multistrike narratives. One of them could have a main problem that lies at the top so theoretically, could only reach a very limited audience. And that stays at the top every strand is kind of very intellectual, very abstract, and so its chances of reaching a wider audience is actually quite limited. While if you take a story like crash where yes, you have a main problem, which is which lies at the top of the pyramid. But each problem in each strand actually reaches much lower down the pyramid that widens its potential audience and I think that's one of the reasons why why quassia met an audience which was bigger than probably what even the filmmakers were expecting

Alex Ferrari 54:30

a very much very much I didn't expect to win the Oscar either.

Emmanuel Oberg 54:34

No but but it's it's it's a very well crafted and very well designed story from from from any point of view but but but especially from from that one, from the idea of trying to find elements in when your main problem sits at the top trying to find elements in your story that which lower to widen your potential audience. It's also something that can be useful when we think about about story design.

Alex Ferrari 54:59

Now I'm I'm going to ask you a few questions. I asked all of my guests. What advice would you give a screenwriter wanting to break into the business today?

Emmanuel Oberg 55:09

I would say, I think for me, it's three things. It's about craft. It's about ideas, and it's about connections. So I would say, you know, work on all three. I mean, there are more than that. But that's the first three that that come to mind. I think, I think if you I think if you if you work on, on your on your craft, you will, you will be able to design better stories. So that that will give you an asset. And if you if you work on, on, on networking and relationship that that's going to help you to put that to future to fruition. It's It's always difficult to give advice to new writers, but I said three things I kind of forgot the third one.

Alex Ferrari 56:01

So no, I don't remember I wasn't. But those first two were good. Those first who were very good. Now, can you tell me what book had the biggest impact on your life or career?

Emmanuel Oberg 56:16

Wet book had the biggest impact on my life or career. I need to get that one right.

Alex Ferrari 56:28

No worries.

Emmanuel Oberg 56:29

No, I would say that might surprise you. But I would say Cyrano de Bergerac

Alex Ferrari 56:34

that's a great book to play.

Emmanuel Oberg 56:37

Because it's just, I guess, I, I find it amazingly written. And maybe it's because I have a French origin. But I, I find the the way it's written very poetic. And at the same time, the way the story is designed is just amazing. And so if you look beyond the surface, which is the dialogue, and you know, the poetry and the way the lines are written, and if you look at the design of the story, it's just really amazing. And I just love the character of siano. I just, I really identified with him, and I can read that, that that play 10 times. And I would cry, you know, just the same. And that's sad. It's beautiful.

Alex Ferrari 57:14

It's a beautiful, beautiful film, a beautiful film and also an amazing book. Now what lesson took you the longest to learn whether in the film business or in life?

Emmanuel Oberg 57:26

Oh, he life will be so many. But in the film business, I guess it's not one it's to the first one was it took me a very long time to forget about my my conscious training. Forget about, you know, it's probably contradict what I just said. But I guess that's that's you mean, but it took me I was lucky enough to get a lot of formal training about, you know, craft and story theory, and so on. And for a long time, I thought that that knowledge was the most important. And I know that the most important, I thought that it was really not necessarily the most important thing in a screenplay, but knowing these things, actually gave me an edge. 10 years to realize that I had to forget them, in a way and to stop thinking about them. And it took me probably 10 more years to succeed in doing that. But it's, it's just this idea that craft is the most important thing. Yes. What's important is master craft, but it's not to think about the craft of to have a conscious knowledge of the craft. What's important is mastery. So and mastery is when you when you when you do it without thinking about it. And it's like the like the cycle in, in, in learning, you know, first you you don't know you don't know. So you you can be in trouble, then you know, that you don't know. So you start to learn about something. And then and then you know, you know, which is very dangerous. And then and then you it's just about moving to a stage where you you your conscious knowledge is not important anymore. And I find that interesting because if you think about it a lot of fantastic writers they never read a book on screenwriting, they never went to a screenwriting workshop and they were fantastic writers. And yes, they worked a lot but they they didn't work they read lots of scripts, they probably worked with another writer because there was a lot of apprenticeship going on and you will learn from from directly from the Masters you know without having to read a book or going through a must to to workshop. But but that that learning was by doing and it was not necessary formalized and I find it fascinating when I when I listened to interviews from even you know someone who was an absolute master of the craft like Billy Wilder, or even Alfred Hitchcock, I mean, they take just to example they had a fantastic mastery of the art, but not from a conceptual point of view. And and so you the idea that either you you Find a way to master it unconsciously. And it doesn't matter if you're not able to, to say how it works and how you use it. Or if you do learn consciously to try to improve what you're doing, then finding find a way to forget about that and to realize that it's not the most important that you have to go back to kind of unconscious state where you where you do it without, without thinking. Yeah, I

Alex Ferrari 1:00:22

mean, I was listening, I read the book on writing with Stephen King. And, and he was one of those guys is like, Look, you the craft is the craft, you know, you first need to learn English if you're writing in English, and you need to learn grammar. But you're not consciously thinking of grammar, because you either know it, or you don't. There's no middle ground. And if you're thinking about grammar, as you're writing about that's bad. I mean, you could think about it when you're editing. But not in the creation process. And and as I was I use the example of like a carpenter carpenters not thinking about how he's cutting the wood or, or sanding the wood. He's just doing it because he's done it 1000 times he has mastery over that skill. And I think that is a very difficult place to be in the creative arts, for filmmaking and for screenwriting, but it's where you need to get to.

Emmanuel Oberg 1:01:15

Yeah, ideally, yeah.

Alex Ferrari 1:01:17

Now, three of your favorite films of all time. Oh, yes. The toughest question of all times

Emmanuel Oberg 1:01:23

of all

Alex Ferrari 1:01:24

time, the whole this will be on your tombstone. So make account.

Emmanuel Oberg 1:01:29

I'm going to take one, which really is one of my favorite films of all damage Jaws, those doors, because I just I think it's fantastic characters. It's full of suspense. It's just

Alex Ferrari 1:01:41

in holes to this day it holds. Yeah, absolutely. You can watch it right now. And with the mechanical shark with everything, it's still a It's a masterpiece.

Emmanuel Oberg 1:01:53

It is. So that's the first one that comes to mind. One of my very recent, fairly recent, fairly recent one is Birdman. But I, I just loved Birdman was surprised by it, because I was not, you know, I try to read and and find out as little as possible about films, especially films that I want to watch. I never read reviews, I just go, that's a filmmaker I'm interested in I want to watch that film. So I was I was I was just completely taken by it. And as always, it's very subjective. You know, it's, it's, it's depends on who you are, at what point you are in your life and how you can relate to characters and you know, whether you connect with a theme and stuff like that, well, I thought it was an amazing film. So that would make it to my list as well. One last one. I love thrillers and I would put I will be really tough called between the silence of the lambs and

Alex Ferrari 1:02:58

the fugitive. Excellent films, they can both be on your list. They're amazing. I would

Emmanuel Oberg 1:03:03

I would put one of these on it because I just I love the kind of psychological fillers that that were made in that era of the 90s we still make great thrillers, but these kind of thrillers I'm thinking about the especially The Silence of the Lambs becomes more difficult to see. And I would I'm not going to talk about the ending like we did about about dutse If you've not watched The Silence of the Lambs, definitely watch it if you if you lost feelers it's, it's

Alex Ferrari 1:03:32

it's one of the it's actually one of the few horror films they call it a horror even though it's a thriller. But or they call it a thriller, but it's really kind of a horror.

Emmanuel Oberg 1:03:42

It's a Thriller Horror. I mean, it's it's, it's both,

Alex Ferrari 1:03:45

but it won the Oscar, it won the Oscar, it won all four big awards that year. I remember it is amazing, amazing film now, where can people find you and you're writing your book, all that kind of good stuff?

Emmanuel Oberg 1:03:58

Well, they can find me on on our website, which is a screenplay unlimited. That's the name of my company. And I have a special link for for your listeners. Oh, awesome. Yes, which is a link where they can find some information about the book that I wrote, which is called screenwriting and unchained. And it's, they will be able to download a free sample of the book, which is the first 50 pages, which is most of the first chapter on the introduction where there's an explanation of the method and and so if they like it, they can purchase the book and if they don't like it, they save some money.

Alex Ferrari 1:04:41

Thank you so much for that. I appreciate it.

Emmanuel Oberg 1:04:43

Give you the link. Thing The link is spin. Screenplay. unlimited.com forward slash indie, what is it?

Alex Ferrari 1:04:54

Yeah, yes. Yeah, I'll put that in the show notes as well. Emmanuel, thank you so much for taking the time to come and talk. Arkansas.

Emmanuel Oberg 1:05:01

Thank you very much for inviting me.

Alex Ferrari 1:05:03

I want to thank Emmanuelle for coming in and dropping some knowledge bombs on the tribe. Thank you so, so much Emanuelle if you want to get a link to the book, or any of the other things that a manual has to offer, please head over to the show notes at Indie film hustle.com forward slash BPS 039 And if you haven't already, please head over to screenwriting podcast comm and leave a good review on iTunes for the show. It really, really, really helps us out a lot. I seen a lot of great reviews coming out lately. So thank you. Thank you so much, guys. For all the support I truly truly truly appreciate it. And that's it for another episode of The Bulletproof screenplay podcast. As always keep on writing no matter what. I'll talk to you soon. Thanks for listening to the bulletproof screenplay podcast at bulletproof screenplay calm that's b u ll e t e r o f s CR e en PLA y.com

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

Please subscribe and leave a rating or review by going to BPS Podcast

Want to advertise on this show? Visit Bulletproofscreenwriting.tv/Sponsors