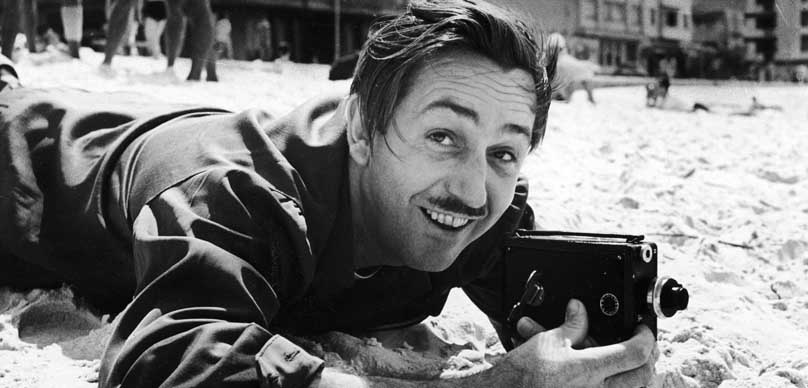

Walt Disney is by far a giant in many realms, storytelling being one of the biggest. His ability to produce monster hit film after monster hit film is a testament to his knack for telling and constructing an intriguing story.

Below is a memo, written by Walt Disney on December 23, 1935, to a highly respected art teacher from Chouinard Art Institute, Don Graham. Mr. Graham was in charge of training Walt’s animators. If you are a writer, director, or filmmaker this is essential reading. I have the transcript below, as well as the original memo. Enjoy.

WALT DISNEY PRODUCTIONS

INTER-OFFICE COMMUNICATION

DATE DECEMBER 23, 1935

TO DON GRAHAM

FROM WALT

Right after the holidays, I want to get together with you and work out a very systematic training course for young animators, and also outline a plan of approach for our older animators.

Some of our established animators at the present time are lacking in many things, and I think we should arrange a series of courses to enable these men to learn and acquire the things they lack.

Naturally, the first most important thing for any animator to know is how to draw. Therefore it will be necessary that we have a good life drawing class. But you must remember Don, that while there are many men who make a good showing in the drawing class, and who, from your angle, seem good prospects – these very men lack in some other phase of the business that is very essential to their success as animators.

I have found that men respond much more readily to classes dealing with practical problems than to more theoretic treatment. Therefore I think it would be a very good idea to appeal to these men by conducting these classes with a practical approach in mind.

In other words, try to show in these classes that the men can make immediate practical application of what they are being taught.

The talks were given by Fergy, Fred Moore, Ham Luske, and Fred Spencer have been enthusiastically received by all those in attendance. Immediately following these talks, I have noticed a great change in animation.

Some men have made close to 100% improvement in the handling and timing of their work. This strikes me as pointing a way toward the proper method of teaching in the future.

The following occurs to me as a method of procedure:

Take the most recent pictures – minutely analyze all the business, action, and results, using the better pieces of animation as examples going thru the picture with these questions in mind:

- What was the idea to be presented?

- How was the idea presented?

- What result was achieved?

- After seeing this result – what could have been done to the picture from this point on, to improve it?

Encourage discussion on the part of the men present; if possible, have some of the animators over to talk to them about the problems they were confronted within the picture, and what the animator himself would do if he had the chance to do the animation over.

I believe these classes could be combined for presentation to all the animators, young and old as well.

It wouldn’t be bad if you made up a list of the qualifications of an animator in order of importance. Then all these men could see what it takes to be an animator and could check on themselves to see how nearly they approach the desired perfection.

The list should start with the animator’s ability to draw; then, the ability to visualize the action, breaking it down into drawings and analyze the movement the mechanics of the action.

From this point, we would come to his ability to caricature action – to take a natural human action and see the exaggerated funny side of it – to anticipate the effect or illusion created in the mind of the person viewing that action.

It is important also for the animator to be able to study sensation and to feel the force behind sensation, in order to project that sensation. Along with this, the animator should know what creates laughter – why do things appeal to people as being funny.

In other words, a good animator combines all these qualities:

- Good draftsmanship

- Knowledge of caricature, of action as well as features.

- Knowledge and appreciation of acting

- Ability to think up gags and put over gags

- Knowledge of story construction and audience values

- Knowledge and understanding of all the mechanical and detailed routine involved in his work, in order that he may be able to apply his other abilities without becoming tied up in a knot by lack of technique along these lines.

This is all very rough – just a jumble of thoughts – but what I plan is that we get together after the holidays, as suggested above, and really get these plans worked out in detail. Then we should strive to see that all the men whom we are drilling for animators are given the chance to develop along the lines outlined.

I am convinced that there is a scientific approach to this business, and I think we shouldn’t give up until we have found out all we can about how to teach these young fellows the business.

The first duty of the cartoon is not to picture or duplicate real action or things as they actually happen – but to give a caricature of life and action – to picture on the screen things that have run thru the imagination of the audience to bring to life dream fantasies and imaginative fancies that we have all thought of during our lives or have had pictured to us in various forms during our lives. Also to caricature things of life as it is today – or make fantasies of things we think of today.

The point must be made clear to the men that our study of the actual is not so that we may be able to accomplish the actual, but so that we may have a basis upon which to go into the fantastic, the unreal, the imaginative – and yet to let it have a foundation of fact, in order that it may more richly possess sincerity and contact with the public.

A good many of the men misinterpret the idea of studying the actual motion. They think it is our purpose merely to duplicate these things. This misconception should be cleared up for all. I definitely feel that we cannot do the fantastic things, based on the real, unless we first know the real. This point should be brought out very clearly to all new men, and even the older men.

Comedy, to be appreciated, must have contact with the audience. This we all know, but sometimes forget. By contact, I mean that there must be a familiar, sub-conscious association.

Somewhere, or at some time, the audience has felt, or met with, or seen, or dreamt, the situation pictured. A study of the best gags and audience reaction we have had will prove that the action or situation is something based on an imaginative experience or a direct life connection.

This is what I mean by contact with the audience. When the action or the business loses its contact, it becomes silly and meaningless to the audience.

Therefore, the true interpretation of caricature is the exaggeration of an illusion of the actual; or the sensation of the actual put into action. In our animation, we must not only show the actions or reactions of a character, but we must picture also with the action the feelings of those characters.

My experience has shown me that the most hilarious of comedies is always based on things actual, possible, or probable. That idea, behind the things I just mentioned above, can be incorporated in every stage of instruction – from the life drawing clear on thru to the planning and staging of the work.

I have often wondered why, in your life drawing class, you don’t have your men look at the model and draw a caricature of the model, rather than an actual sketch. But instruct them to draw the caricature in good form, basing it on the actual model.

I noticed a little caricature of one of the models in the life class made by Ward Kimball, and it struck me that there was an approach to the work that we should give consideration. I don’t see why using this method, you can’t give the class all the fundamentals of drawing the need and still combine the work with the development of a sense of caricature.

Would it be a good idea to take a man like Joe Grant and see what could be worked out with him along the lines of giving a talk some night on an approach to caricature, a Harpo caricature – what he sees and what he thinks about when he is trying to make a caricature. It might be advisable to have a talk with Joe on this.

I started out early last fall to work out some sort of system with you for teaching elementary phases of animation in a systematic way. My thought at that time was not to go too straight. That’s why I wanted to get somebody to demonstrate various walks in a comic way.

I still think this is a very good idea and constitutes a far better approach for the younger men than giving them too many straight natural things that direct their minds to the unimaginative end of the business. It is possible that with the comedy, you can still teach them the fundamentals of all these actions.

Take, for example, the walk. Why can’t you teach the fundamentals of a straight walk yet combine it with some person that is giving an exaggeration or a comic interpretation of a straight walk?

Perhaps for very elementary instruction, it might be best to present straight action; but not to keep giving them straight action as they progress and gain a little experience… Start them going into the comedy angle or caricature angle of the action.

For example – a fat person, with a big pot belly: What comedy illusion does he give you?

You could at the same time instruct the classes regarding the reason why he has to move a certain way (because of his weight, etc.) Present the walk soliciting discussion on:

- What illusion does that person, fat with pot-belly, give you as you see him?

- What do you think of as you see him walking along?

- Does he look like a bowl of jelly?

- Does he look like an inflated balloon with arms and legs dangling?

- Does he look like a roly-poly?

In other words, analyze the fat person’s walk and the reasons for his walking that way… BUT DON’T STOP UNTIL YOU’VE HAD THE GROUP BRING OUT ALL THE COMEDY THAT CAN BE EXPRESSED WITH THAT FAT PERSON’S WALK; also all the character – but drive for the comedy side of the character.

Take a skinny person – somebody that’s loose-jointed, angular, shoulder blades showing – what does he suggest? Does he look hung together with wires like a walking skeleton? Does he look like a marionette flopping around? Does he look like a scarecrow blowing in the wind? What illusion is created by the walk, by the movement, of that skinny loose-jointed person?

In discussing a short person, with short legs – he would naturally have quick movements – seems to move very fast – would have to take twice as many steps as a taller person, thus making him look as if he were going at a greater speed. What illusion do you get from a person like that? Does he strike you as a little toy wound up and running around on wheels? Does he look like a little Pekinese pup? A dwarf?

There are a number of things that could be brought up in these discussions to stir the imagination of the men so that when they get into actual animation, they’re not just technicians, but they’re actually creative people.

In the study of other problems, is it possible to bring out more the exaggeration of form and action – as in the study of the balance of the body? Can we bring that out even to an exaggerated point? It will probably make it stronger to them – make them realize more the necessity of that balance of the body – and yet point out how they can utilize that to strengthen their business when they get into animation, as in bending.

In someone bending over – can we show the exaggeration in that action by showing how the pants pull up in back to an exaggerated degree that becomes comical? Can we show how the coat stretches across the back, and the sleeves pull up and the arms seem to shoot out as from a turtle-neck as they shoot out of the sleeves? What can we do to bring these points out stronger to the men?

In lifting, for example – or other actions – we should drive at the fundamentals of the animation, and at the same time, incorporate the caricature. When someone is lifting a heavyweight, what do you feel?

Do you feel that something is liable to crack any minute and drop down? Do you feel that because of the pressure he’s got, he’s going to blow up, that his face is going to turn purple, that his eyes are going to bulge out of their sockets, that the tension in the arm is so terrific that he’s going to snap?

What sensations do you get from someone rising – different ways of rising? Sitting? When somebody is sitting – when he sits down and relaxes, does it look as if all the wind goes out of him? Does he look like a loose bag of nothing?

Also, in pushing… in the extremeness of a push, the line shoots right down from the fingertips clear down to the heel. In pulling – show the stretch, and all that. Bring out the caricature of those various actions, at the same time driving at the fundamentals of them – the actual.

The various expressions in the body are important. The animators go through animation and don’t make the positions of the body – hold positions and relaxed positions – express anything. They try to do all the expressions with the parts that are moving, whereas the body should enter into it. Without the body entering into the animation, the other things are lost immediately.

Examples – an arm hung on to a body it doesn’t belong to, or an arm working and thinking all by itself. I think something could be worked out to develop this point, even if you got a person up behind a screen, a model perhaps, and threw a light on them.

Have the class do nothing but watch the silhouette as the model goes thru different poses, noting how the body enters into the expression of an action.

Or we could photograph the action to show to the men. The study of this would be a big help toward making the men realize the value of getting the story and the business over in the rough drawings that are the action itself, rather than depending on little trimmings, on the clothes, facial expressions, and things like that to put over the business.

If the animators get the groundwork right, that is, the action underneath all these trimmings right – then what they add is going to be twice as effective. It’s a very important point that we must impress on the new men and the older men.

After we have given the men all the suggestions we can that have to do with expressing ideas through the body, then we can come down to the value of the facial expression – the use of the eyes, eyebrows, the mouth – their relation to one another – how the eyes and the mouth have to work together sometimes for expression – how they may work independently for expression at other times.

In other words, then we would go into the combined use of expressive features and expressive actions of the body. Then it would be good to take one away from the other and see which is the most important.

We should have courses in staging and planning. These courses can be given by some of our more successful animators.

Also, we should try to show how to analyze a scene or piece of business before starting to work on it. We should try to show the men ways of visualizing action in their minds, breaking the action so that the men are prepared in advance to begin animation of the action and know thoroughly what they are going to animate.

So many of the men start in now and have no idea what they’re going to do when they start the scene. They know what they’re supposed to do, but they can’t break it down in a systematic way that will enable them to go knowingly ahead.

Many men do not realize what really makes things move – why they move – what the force behind the movement is. I think a course along that line, accompanied by practical examples of analysis and planning, would be very good.

In other words, in most instances, the driving force behind the action is the mood, the personality, the attitude of the character – or all three.

Therefore, the mind is the pilot. We think of things before the body does them. We also do things on the spur of the moment by the reaction to stimuli that are telegraphed to the mind by the nerves, etc.

There are also things carried out by the subconscious mind – reflexes, actions that have become habit through repetition, instincts. In other words, the subconscious mind is an assistant oftentimes in carrying out things that may or may not have been taught, Examples of that are sleeping, lighting a cigarette and throwing a match away without any thought, whistling, walking, running, sitting, etc. It’s not necessary to think of those actions.

But certain actions we do think about – certain actions we deliberately plan. We plan them very quickly in our minds. The point to bring out here is that when a character knows what he’s going to do, he doesn’t have to stop before each individual action and think to do it.

He has planned in advance in his mind. For example – say the mind thinks, “I’ll close the door – lock it – then I’m going to undress and go to bed.”

Well, you walk over to the door – before the walk is finished, you’re reaching for the door … before the door is closed, you reach for the key … before the door is locked, you’re turning away – while you’re walking away, you’re undoing your tie – and before you reach the bureau, you have your tie off. In other words, before you know it, you’re undressed – and you’ve done it with one thought, “I’m going to go to bed.”

A lot of valuable points could be brought out to the men in showing them that it is not necessary for them to take a character to one point, complete that action completely, and then turn to the following action as if he had never given it a thought until after completing the first action. The anticipation of action is important.

This enters into animation in many ways and we have many serious difficulties coming up because of the men’s inability to visualize things in the proper way.

I think a good study of music would be indispensable to the animator – a realization on their part of how primitive music is, how natural it is for people to want to go to music – a study of rhythm, the dance – the various rhythms that enter into our lives every day – how rhythmical the body really is – and how well balanced the body really is.

That, in itself, is music. In other words, it could be music in the body. We dance – we can keep time to the rhythm without ever being taught – a baby does it – cannibals do it. But fancy dancing or any trick stuff, we have to learn. There are things in life that we do to

There are things in life that we do to a rhythm that come naturally to us. Notice how rhythmic an action like pounding with a hammer is! There’s a reason for that. You must have that rhythm or you can’t carry out that action completely.

Also, saw aboard. See how necessary it is to have a good rhythm for that. Also, walking … if you walked without rhythm, where would you get? You’d have to be thinking all the time what to do next. You’d have to set your mind to walking rhythmically, instead of doing it naturally.

Naturally, the body is very well balanced. When one hand dose something, the other serves as a balance to it. There are various things that combine balance in the body – subconscious balance … and yet the animators do not know it.

They will do something with one hand – they don’t know what to do with the other, so they will do something entirely contrary to what that hand should be doing because they don’t understand the basic concept of balance. This idea of the balance of the body ties in with the idea of the expression of the body. If there is balance, it adds expression to the things that the body is doing.

If you don’t have that balance of the body, then your expressions are wrong, insincere, unconvincing. Those concepts also tie in with overlapping action.

In other words, we could work out all these basic concepts in such a way as to show them all related, interdependent, and have to do with each other, and we could tie them together in various ways, showing different combinations of their application.

We will thus stir up the men’s minds more, and they will begin to think of a lot of these things that would never occur to them otherwise if the way weren’t pointed out to them.

I’d like also to have a study of dialog. I want to prepare a course on dialog – phrasing, and rhythm of dialog, moods, and character of dialog, expressions, gestures, directness, use of the eyes, eyebrows, mouth, head, arms, body, tongue, inhalation and exhalation, and various other aspects that have to do with the successful picturization of dialog in the cartoon.

Let’s see if we can’t organize something like this and get it going right after the first of the year.

– Walt Disney