Right-click here to download the MP3

LINKS

SPONSORS

- Bulletproof Script Coverage– Get Your Screenplay Read by Hollywood Professionals

- Audible– Get a Free Screenwriting Audiobook

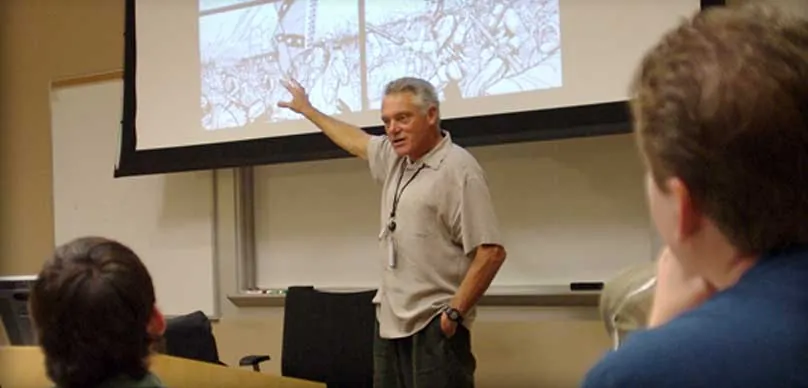

Alex Ferrari 4:00

So, today's show, I wanted to give you a sneak peek at the Hollywood directing masterclass course that we released with Gil Bettman. And it is a game changing course. And I wanted to give you one of the lessons for free so you guys could listen to it. Just see what kind of cool stuff Gil does. I mean, I mean, I've been directing for 20 years. And you know, when I watched this course and took this course, Gil gave me all sorts of ideas I just did not have before, and it's one of the best rated filmmaking courses on Udemy right now, and without any further ado, here is a lesson on how to amp up your static shots just by using lenses. And you know how much I love my lenses. So it's kind of a little masterclass on Lensman ship, as he calls it and enjoy it guys. I think you guys are gonna get a lot out of it

Gil Bettman 4:58

Though different lenses. lend themselves to different kinds of shots. Okay? So if we're talking about field of vision and depth of field, all right, the one with a wide angle is you've got you can see, you know, the world the entire world. Okay, so what would be a good shot to do with a wide angle lens? A BB a big shot as part of a big master okay, but but specifically what what subject you kind of want to do any a city or even if you want to do a shot in a bathroom, you want to get the entire bed. Yeah, all right. But but that's a little atypical. But, but basically with a with a wide angle lens when you're talking about if it's big, and you want to see all of it, right? Use a wide angle lens to basically it's your establishing lens, because you see all of it. And it's all in focus. So a big room or a typically a big room or a big Stadium, right. This is this is the thing about a normal room will look the true size, not with a 50 millimeter lens, but with a with a wide angle, okay, because of the field, the field of vision property, the telephotos are good for something which is like if you if you have one thing and you want to eat you want it to fill the frame, and to be that which is like the isolette you want to isolate something in a frame, like this shot of a butterfly, okay? This is a good application of a telephoto lens, right? Because you see, only this one thing because of the narrow field of vision, right. And because of the narrow depth of field, only the butterflies in focus, everything else is soft. This is the Brooklyn Bridge with a wide angle lens. And you see all the braids and much of the Manhattan skyline behind it. Okay, so if it's big, and you want to see all of it, use the wide angle lens because of the wide angle lens is the ability to show you. Great field of vision and great depth of field. Okay, that clear? Now, you're talking about applications of lenses, in terms of in terms of perspective, okay? The way that the way that perspective changes the way that things look, with a wide angle lens, it makes objects look bigger, or more bulkier, or more bulbous more round, right. I mean, a perfect example if, if you had a beautiful Greek column, if this is the Greek column, all right of the Parthenon, and I shot it with a wide angle lens at this height with a nine five lens. Okay. What would it look like? Exactly, Angeles guy, it would be it would taper to the top, taper the bomb and be fat in the middle. Is that aesthetically pleasing? No. Because it's made what what is graceful has been made bulky and bulbous. Okay, but some things look good, bulky and bulbous. What can you think of which looks big? Good. If it's big and fat and juicy. A burger is a burger is closer to it. All right, a burger looks good. big, fat and juicy. What else besides a burger food one of the piece of food? Ice cream or an apple an apple or a tomato? Right? Or a car for some rear reason. cars look nice winner big and curvy. Kind of like girls. I don't know they have biggest thing is not right but curvy. The distortion of a car. You know the lines of a car made curvy by the distortion of the wide angle lens. This this distortion here. The extreme wide angle looks good. Okay, that's the way that perspective alters the way things look. Now with telephoto. It's the opposite. Okay with the extreme telephoto extreme long lenses. You get things look looking thinner. Okay, what looks better thinner? If you're shooting a close up on your leading lady, what was he going to use 35 no 100

Alex Ferrari 9:43

I can't speak more highly about this course. I mean, it's such a great course on directing, and specifically how to move the camera how to get good action sequences, how to tell a story visually. It's just a It's a unique course because there is Not much of anything like this out on line. And it's so well put together and Gil is a, you know, just a amazing instructor. So I definitely advise you guys go out there and check it out, just head over to indie film hustle.com Ford slash directing 19 that's indie film hustle.com, forward slash directing 19. And that'll get you the course for 19 bucks. And normally, the course sells for 200. So definitely check it out, guys. And I wanted to let everybody know in the Los Angeles area that this is Meg is going to have its la premiere at Holly shorts, it's going to be the closing night feature film. And it's going to play at the Chinese theatre, the world famous Chinese Theater, I cannot tell you how excited I am and jealous and we're just so blessed and just so grateful that we're going to be playing at the Chinese Theater, a little movie that we made last year. And it's going to be la premiering there. It's It's such a big deal. So if you guys want tickets, just go to the show notes at indie film hustle.com forward slash 174. And you'll get links there with discount discount codes for tickets. And it's going to be playing August 19 at 8pm. And I'll be there the whole cast will be there. It's gonna be amazing. And we probably go out and get drinks afterwards. There'll be a lot of fun. So definitely check it out, guys. I hope I can see you guys there. I really appreciate all the support. Thank you so much. And as always keep that hustle going keep that dream alive. And I'll talk to you soon.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

Please subscribe and leave a rating or review by going to BPS Podcast

Want to advertise on this show? Visit Bulletproofscreenwriting.tv/Sponsors